Keep Louisville interesting and support LEO Weekly by subscribing to our newsletter here. In return, you’ll receive news with an edge and the latest on where to eat, drink and hang out in Derby City.

Dave Pajo, like so many Louisville expats, has a difficult relationship with the city. It’s not a bad thing. For him, it’s a way of seeing more clearly the place that nurtured him into the musician he has become. He loves his hometown. So much so that because he doesn’t live here, he sees what sometimes holds the city back with some clarity.

It is true that sometimes Louisville lacks the ability to critique itself and its art with any distance. Occasionally, the city can be an echo chamber of our ideals and thoughts about creating. Sometimes, it’s a place where it’s easy to feel an inflated sense of self because the streets and people are so familiar. Getting out of Louisville can put the place and our egos in more perspective.

Few artists in Louisville have had the creative experiences that Pajo has. Dave Pajo was a member of several local bands, from Solution Unknown to Maurice to the revered Slint. He’s played with countless amazing musicians both in town and around the world, most recently joining English post-punk band Gang of Four. His resume is extensive. Pajo has played with Stereolab, Zwan, Royal Trux, Tortoise, Will Oldham, King Kong and the Yeah Yeah Yeahs. Long story short, he’s worked a lot, including his own projects, Papa M, Aerial M, and M.

With great talent, though, often comes struggle, and that struggle found Pajo early with the loss of his brother, which resulted in his brother’s best friend, Mike Bucayu (Kinghorse, Blue Moon Records, and perpetual cousin to real and "adopted" Filipinos everywhere), taking Pajo under his wing and introducing him to the world of local punk rock. Later, these struggles brought Pajo to the brink of suicide with a (thankfully) failed attempt in 2015, and then a devastating motorcycle accident in 2016.

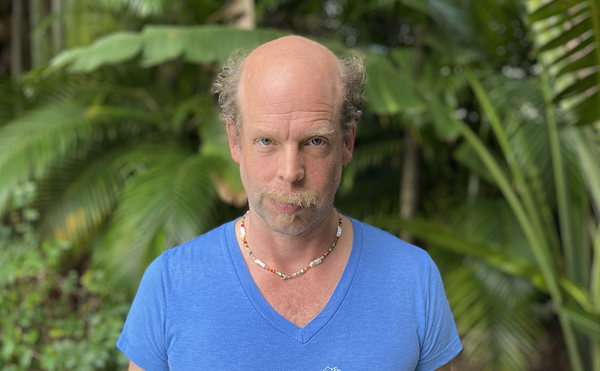

Despite all of his experiences, locally Pajo has been written about far less than many of the other players. Seeing this as a real disparity, LEO decided to give Pajo the space he deserved to discuss whatever he wanted, including his outlook on life, his latest work with Gang of Four and his relationship to music and to his hometown.

LEO: Good morning, Dave. Forgot to ask about the time difference. Is this a good time to talk?

Dave Pajo: I’m on the East Coast right now, so it’s all good. I’m still waking up. Like, I’m just now having my coffee and stuff. My sleep schedule is messed up, but yeah. Thanks for calling.

I guess I should preface that I have such a... I haven’t been in Louisville for so long and I have such a weird love, hate relationship [with the city]. I’m afraid I’m gonna say something bad, but at the same time the love is still real and definitely there. I don’t know. I don’t want to say... I don’t want to talk shit either.

LEO: One of the things that we wanted to do was to diversify the pages and to add a more critical element to the way Louisville sees itself, because Louisville works often in a vacuum. Sometimes, it’s just like we’re in an echo chamber and nobody can critique us, but that’s not going to help artists in the city grow.

I appreciate that. I totally agree with you. And I think if anything, and this is just me, I guess, like, with a lot of hindsight: Louisville always benefited when Louisvillians left Louisville.

I’ve always been under the notion that the punk scene in Louisville was kind of started around the Louisville art department or the liberal art college that used to exist in the late ‘70s. Then people would go to New York, and they would come back with these records, and just kind of turn people on to cool music.

It’s like Gang of Four’s history too. There were these young guys from Leeds who went to New York and they actually stayed. They were staying above CBGB. So they just saw all these amazing bands, mid-’70s, every night. And then they came back to Leeds informed, you know. So I think a lot of times, you can’t just be insular and just stay in your circle and just pat yourselves on the back and prop each other up all the time. You have to leave and get uncomfortable, out of your comfort zone, and then bring it back, then internalize it and make it your own. So I think Louisville is at its best when it does that.

LEO: We agree.

You don’t even have to leave for a long period of time. I feel like just shaking up your world or just like getting some sort of perspective by leaving Louisville. ‘Cause Louisville is a small town, and that’s one of the things that I love and hate about it. You know, it is a small town, and it’s beautiful in that way. And, at the same time, there was a shit load of gossip, but just... it’s like a tornado — a constant tornado. I love so many people there. You know, my family is still there and then I almost feel like I get sucked into that tornado. The gossip part of it is something you have to at least relieve yourself from now and then, whether it’s meditation or physically leaving, you know, like you have to get away from that kind of insular thinking.

LEO: Everyone knows everyone, especially if you’re involved in arts and music.

I think it wasn’t until, like, the straight-edge scene. What were the bands... like, Endpoint and I think when Kinghorse kind of blew up, then I would go to shows and I’d know like a dozen people maybe, but before that it was like, the scene was so tiny that it was like this little dysfunctional family, you know. But we all, even if we didn’t get along with every single person, it was like, ‘Oh, he’s like the drunk uncle,’ or ‘He’s great until he gets drunk.’

[Dave and I chat a few more minutes about characters in the local punk scene that we both knew. We then switch gears and discuss his life in conservative Orange County, the Breonna Taylor protests and some other parts of life during the pandemic before we land on a bit of his backstory and how he came to punk rock and music.]

LEO: How did you get involved with punk in Louisville?

My older brother was friends with Mike [Bucayu]. Mike was always, like, the bad kid. Yeah. I was a bad kid too, but I was like more of a metalhead type. My brother would crank, like, Dead Kennedys and Pistols and all, but also like all this new-wave stuff when he would take me to school. And I liked it all. I thought it was all really funny, but I never took it really seriously. I thought they were just really funny, and they said bad words and stuff. I liked Jello’s (Jello Biafra of the Dead Kennedys) lyrics a lot.

It wasn’t until when my brother passed away and Mike and I ended up bonding. Then he got me into Maurice, which, when we broke up, we became Slint and Kinghorse. That’s when I was actually introduced to this scene, and it was at a time when I needed it. I was used to being, like, an outsider my whole life, even amongst metalheads, like, I still felt too different, but once I found the punk scene, I was like, ‘Oh great. We’re all weird.’

LEO: Same, that’s how I felt when I found punk. Tell me about the Gang of Four.

I’ve been reading different bios on Gang of Four, now that I joined, just to make sure I don’t pester them with questions they’ve been asked a million times. The early Leeds scenes that Gang of Four and The Mekons were part of, it was based around the art school. It reminds me a lot of the old Louisville scene, and so I’ve been thinking about it a lot.

One thing that I think is a true blessing about both worlds is that in Louisville when I was younger, it was really encouraged to sound like yourself. It was really encouraged to not sound like other people. You could steal from whoever you wanted, but when you had your own band, it just had to be you. And I’m thinking specifically about bands like, Babylon Dance Band, The Monsters, Malignant Growth and Your Food. Each one of them distinctly sounded like themselves and not like any other band, but they all hung out and were all part of the same world. But if you came out and sounded exactly like Velvet Underground, you would kind of be laughed at.

It was really encouraged to just be yourself. It was that same mentality in Leeds.

That attitude’s always been below the surface in Louisville, and there’s alway great music happening as a result. Just people encouraging people to do their fucking thing. I love that, you know. That’s what it’s all about.

LEO: But, how did you get out of Louisville?

I ended up buying a house in St. Matthews for super cheap, and it became a home base. I didn’t have any pets or plants or anything, so I could leave and live in Chicago. I could leave and live in New York and I could live wherever, and then I always had a home base in Louisville.

LEO: So you went to art school in England?

Yeah, I guess after Slint broke up, I didn’t realize it at the time, but I guess I was so disillusioned. I was like, maybe I should put myself fully into music. Like maybe, I should put myself fully into art because I really never have. So I went to England and, for the first time, since I got a guitar and played it for hours every single day — I left for England and didn’t even bring a guitar with me. I could only last a few months before I borrowed a guitar.

I realized that painting is probably the loneliest occupation you can choose. I’m such a loner or such a solitary person as it is, music is the only thing that pulls me out of my shell. I need to collaborate with people and stuff. And with art, you don’t need to at all. So I was really withdrawing into myself, and without a guitar. I realized the guitar is no longer something I can take or leave, it’s something I need just as much as things like food and water. It’s just the way it is.

LEO: When did you finally decide to devote yourself to music?

I can tell you the moment when I decided that it was going to be music. I was living in Old Louisville. I was living with my partner, and we were just really, really poor and in love. It was great.

I remember I was working at System Parking and food stamps would all go to one week’s worth of groceries, you know? And I’m like, oh my God, what am I doing? At some point I did the math. It took me long enough, but at some point, I realized I was living off of Slint royalties, which must have been like ‘92 or ‘93 or something. And I was like, why am I, why am I working this job that I hate?

With food stamps every month, you have to go in and prove that you’re poor, basically. It was so humiliating to do that every month. I felt like such a piece of shit. I hope they don’t still do stuff like that. It felt really degrading.

At one point they were like, ‘How much money do you have in your pockets?’ And I was embarrassed because I had a $20, which was just for an emergency. But, yeah, at some point I was sitting in that little parking lot thing and I was like, why am I doing this? I’m basically living off the Slint checks that were starting to come in. And like, both of us are living off of this, and that’s what I love to do.

I quit my job. And I just decided I was going to put myself fully into music. And that’s when Tortoise needed a bass player. Things started happening right then, as soon as I made that decision, it was really weird. My whole life that’s happened to me enough times now to where I trust myself to make it through the dark droughts.

LEO: What is something that you feel is important?

In 2015, I had a suicide attempt. And then in 2016, I had a crippling motorcycle accident where they were going to amputate, and I was in a wheelchair for two years. That kind of stopped all the music stuff. I still recorded an album, but that stopped the touring. I went through 13 surgeries just to save my leg, just to keep my real leg. It’s still fucked up, like I’m technically handicapped. I still have my wheelchair that I lived in for two years, just in case. ‘Cause all it takes is one bad thing. I could just fall and I’m back in the wheelchair.

I feel like my adventure and my story is pretty far from over. Since I joined Gang of Four, I have that excited feeling again. It’s pretty fun and awesome to know that your story doesn’t have to ever end. For anyone that feels like they want to cash in their chips, there’s a lot more. Everything I’m going through is a bonus. So when I’m self-loathing and depressed and angry, even then, I’m just like, ‘But I’m really happy to be here to experience all this.’ It’s like it’s still a part of me. This is like bonus life. Technically, I shouldn’t be allowed to have this experience right now, but I’m here.

All those facets of that kaleidoscope is what makes you who you are, and that’s what makes the art beautiful and the product becomes beautiful because it has more dimension to it. It’s not just flat and shallow because you’re, you’re not complicated. I don’t know. I like simple stuff, too. So it’s hard to say, but I think a lot of this stuff is just having the balls to be yourself.

CORRECTION: A previous version of this article gave the wrong name for the parking garage, System Parking, where Dave Pajo used to work.