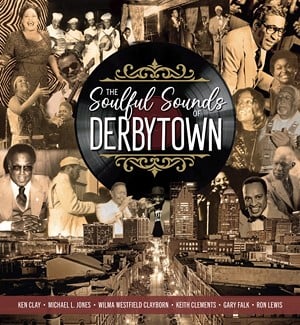

Carol Butler, cofounder of Butler Books, is fond of saying that books are born when they are ready. “The Soulful Sounds of Derbytown,” Butler Books’ latest release, had a particularly long gestation period. When this history of African American music in Louisville is released on March 2, it will be nearly a decade since the project was first conceived

I am one of six co-authors of the new book, and I served as its executive editor. “The Soulful Sounds of Derbytown” explores the legacies of Black musicians and entertainers in Louisville through hundreds of biographical sketches, historical essays, information on music venues and promoters, and historical and contemporary photographs that document a wide range of genres, including gospel, jug band, blues, jazz, R&B, hip-hop, rock, and classical and theatrical music.

I don’t know if I or my collaborators — Ken Clay, Wilma Westfield Clayborn, Keith Clements, Gary Falk, and Ron Lewis — would have pursued this venture if we’d known how time consuming it would become.

This project began as a photo exhibition held at the Kentucky African American Heritage Center (KAAHC) in February 2014. Ken Clay, the founder of the nonprofit Legacies Unlimited Inc., is a well-known local music promoter. Not only did he launch the Midnite Ramble concert series at the Kentucky Center for the Performing Arts, but he helped to organize the city’s annual World Fest concert for many years.

Clay, a coauthor of the book “Two Centuries of Black Louisville,” has hosts the two-day festival “Celebrating the Legacy of Black Louisville” at KAAHC each year. In 2014, he decided to put together a photo exhibition focused on the legacy of Black musicians and entertainers in the River City. Ken assembled a dream team of people who had spent their lives immersed in the local music scene to collect photos and information from the local musicians they knew.

The group included Clements, a former blues columnist for “Louisville Music News” and board member of the Kentuckiana Blues Society; Lewis, a longtime R&B musician and owner of Mr. Wonderful Productions; and Falk, a longtime jazz musician and the owner of the recording studio Falk Audio. The University of Louisville Photo Archive and Special Collections also contributed to the exhibition.

I was asked to join the group because I spent more than a decade writing about the Louisville music scene for LEO in the ‘90s and early ‘00s. I am also the author of “Louisville Jug Music: From Earl McDonald to the National Jubilee,” which actually began as a LEO article.

The photos were laid out along the walls in the main hall of the heritage center. It was a timeline of Black music in Louisville from Cato Watts, a slave fiddler who was among the city’s first settlers, to the contemporary vocal group Linkin’ Bridge. When local philanthropist Christy Lee Brown saw all that history assembled in one place, she suggested it should be a book. It would be 2016 before we started having regular meetings that would lead to “The Soulful Sounds of Derbytown.”

When it came down to write the book, Clay asked Wilma Clayborn, a longtime choir leader and the owner of the city’s first Gospel record store, to join the group of authors. He also reached out to Christopher Doane, who was then the dean of the University of Louisville’s School of Music, and asked if he and UofL could assist us with the project. Doane recommended Samantha Holman, who was then a graduate student at UofL’s School of Music, to help our team organize material as we collected it.

At the time, we did not realize how ambitious an assignment we were giving ourselves. We spent eight years conducting interviews and searching archives and attics. We also spent countless hours tracking down dates, spellings of names, and legal names to go with professional monikers like “Eggeye,” “Eggie,” and “Church.” This work continued through a global pandemic, several surgeries for group members, and other major life events.

Despite all that time and effort, we know we’ve missed some people. The depth of talent produced by the River City was deeper than even we had imagined when we started this project. We were still adding new biographies and photos almost to the moment we handed the files off to the printer.

“The Soulful Sounds of Derbytown” will finally greet the world on March 2 at the Kentucky Center for the Performing Arts at 7 p.m. The book launch will be accompanied by a concert featuring the Jerry Tolson Quartet, Marjorie Marshall, Mark “Big Poppa” Stampley, the Walnut Street Blues Band, Toni Green, Tyrone Cotton, Tanita Gaines, Sheryl Rouse, Christopher “Chris Flow” Forehand, the Imani Dance Company, Jerry Newby, Christine Booker, Archie Dale and the Tones of Joy, Jason Clayborn, and In God’s presence.

The authors will be available to sign books after the show. Tickets to the event start at $49.

I and my fellow authors are excited to share our work with other Louisvillians. But until then, here a couple of excerpts from the book so you can see what we’ve been doing all these years.

The Gospel Era in Louisville

This study of African American music in Louisville Kentucky, begins with a discussion of religious music because the Black church is the foundation of African American culture.

The church played a role in the retention of African musical characteristics like group singing, syncopation, and polyrhythms because it provided the initial music training for generations of African American musicians.

Gospel music is the sound most identified with the Black church today, but the genre didn’t begin until the 1930s. Below is an excerpt from the Gospel section of “The Soulful Sounds of Derbytown” that deals with the embrace of the sound by community choirs in Louisville.

William J. Simmons, president of the Kentucky Normal and Theological Institute (now Simmons College of Kentucky) in Louisville, founded the American National Baptist Convention (ANBC) in 1881. It was one of several organizations formed during the period to unite Black Baptist churches. The ANBC merged with two similar organizations in 1886 to form the National Baptist Convention, USA. The Nashville-based organization is still the largest federation of African American Baptist churches in America.

In 1921, the Sunday School Publishing Board of the National Baptist Convention published the first hymnal to carry the word “gospel” in its title. “Gospel Pearls” was an anthology of the most popular songs being sung in Black churches across the nation. It included traditional Protestant hymns, some spirituals, and contemporary songs by African American composers like popular Methodist songwriter Charles Tindley and Lucie Campbell (“The Lord Is My Shepherd”). However, no actual gospel songs were in the Gospel Pearls until the third edition of the hymnal. Later editions included, among other gospel songs, “If I Don’t Get There,” by Thomas A. Dorsey, a former bluesman who is considered the “Father of Gospel Music.”

“Gospel Pearls” was compiled by a 10-member committee of nationally renowned singers, evangelists, and researchers under the direction of Willa A. Townsend, whose composition, “Wade in the Water,” was among the songs included in the hymnal. Also, on the selection committee were Campbell, John W. Work II, and John H. Smiley, an evangelist and celebrated revival singer from Louisville.

Smiley was the oldest son of Charles Bell Smiley, founder of Hill Street Baptist Church. He started out singing in a family sextet, but soon became a solo artist and evangelist traveling the country with his pianist wife, Montra. According to his 1937 Courier-Journal obituary, John “conducted both white and Negro revival services throughout the country and sang several times before the Southern Baptist Convention.” Many of the songs in “Gospel Pearls” were part of his repertoire.

“Gospel Pearls” became the standard hymnal for Baptist churches around the nation. Eileen Southern called it the most influential African American religious songbook since Richard Allen, founder of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, released “A Collection of Hymns and Spiritual Songs from Various Authors” in 1801.

Despite Smiley’s connection to the compiling of this seminal hymnal, it would be several years before gospel music itself was embraced by the city of Louisville.

After abandoning secular music for the church, Thomas Dorsey founded the National Convention of Gospel Choirs and Choruses (NCGCC) in 1932 to inspire choirs and other songwriters to embrace gospel music, which he said merged the good news (the gospel) with bad news (the blues). The Louisville Gospel Choral Union (LGCU), formed by Jasper Shamell and Mildred Goodnight in 1941, was the first NCGCC chapter in the River City. Sonocia Harris, a member of the Harris family singing group, became the choral union’s president in 1948 and held the title for the next 41 years. She helped cultivate generations of gospel singers, musicians, songwriters, and choir directors. Among the notable artists to come out of the LGCU during her tenure were the Gospel Descendants; Keith Hunter and the Witnesses for Christ Choir; Carl Smith, organizer of the University of Louisville Black Diamond Choir; and Henrietta Ruffian, the first singer to perform gospel music at the WHAS Crusade for Children.

Because of its proximity to Chicago, where Dorsey was music director at Pilgrim Baptist Church, Louisville retained close ties to the NCGCC. Dorsey or Sallie Martin, a founding member of the NCGCC, visited the River City annually, and the city hosted the NCGCC national convention on several occasions. Louise Harper, a gospel singer from Louisville with a voice so sweet that Dorsey himself dubbed her the “Songbird of the South,” served as one of the assistants in the NCGCC’s Soloist Bureau. Louisville would eventually be home to three more NCGCC chapters — the Utopia Choral Union, the Louisville Gospel Singers Union, and the Metropolitan Gospel Music Connection.

The Louisville gospel scene was in the national spotlight in 1949 when Gladys Watts became a three-time winner of a nationally televised singing competition, the Ted Mack Original Amateur Hour. Watts was a blind soprano who graduated from the Kentucky School for the Blind. She sang hymns and spirituals like “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” on the Mack show. Her television fame led to a successful career touring churches and revival meetings all over the country.

LGCU member Lucille Jones led one of the first small groups to break out of Louisville. Beginning with 1966’s “The Sensational Sounds of the Traveling Notes,” Lucille Jones and the Traveling Notes recorded several albums for Nashboro, a Nashville-based gospel record label. The group also became a launching pad for several celebrated gospel performers. The most notable veterans of the group were Grammy-winner Alphonso “The Bishop” Hobbs and Mae Newton, who toured with Shirley Caesar.

In the 1950s and ‘60s, Cable Baptist Church hosted impromptu performances from local gospel singers and musicians after its Sunday night service. This event packed the church and inspired other churches to embrace gospel music. Among the first were Stoner Memorial Methodist Church, Greater St. James Methodist Church, Greater Salem Baptist Church, King Solomon Baptist Church, Mount Zion Baptist Church—which were all downtown—and Greater Faith Baptist Church, Star Hope Baptist Church, and Forest Baptist Church in the Newburg neighborhood.

Mary Ann Fischer Meeting Ray Charles at Fort Knox

Mary Ann Fischer was a blues singer who was born in Henderson, Kentucky. After her father’s death she was sent to the Kentucky Home Society for Colored Children in Louisville. Fischer started singing in local clubs, but she was later discovered by Ray Charles. She toured the world as a featured singer with him. The following is a description of the night Fischer and Charles met.

A friend of Mary Ann, Ms. Connie, used to take busloads of people to Fort Knox to hear the US Army Band. One night, Mary Ann went out and sat in with the band and was hired as their vocalist. She enjoyed working at the NCO club because she got good money for playing to an appreciative audience. The soldiers loved her and gave her the nickname, “Little Sister.” She would take her microphone and walk out into the crowd singing to the soldiers. She gave them great relief after their hard work on the base. Sometimes she would tease them and sit on their laps. After she performed, she would return home to Louisville on the bus or get a ride back with a band member.

Early in 1955, Mary Ann was going out to Fort Knox to pick up her monthly paycheck. She was riding on the bus with Ms. Connie who kept talking about how they should hang around and catch Ray Charles’s show. Mary Ann wasn’t very excited about it at first because it was her day off, and she wanted to go back to Louisville. They ended up staying, and she was so glad she did. That evening was about to change her life forever.

When Ray was about to perform, the soldiers started yelling for him to let Mary Ann sing. Then they started chanting, “Let Little Sister sing, Ray,” and he became hesitant. After the crowd wouldn’t give up, he finally said in an irritated voice, “Aw, come on, Little Sister. Damn!” The audience applauded. Mary Ann went up to the microphone and looked at Don Wilkerson, Ray’s tenor saxophone player, and asked him if he knew, “I Got It Bad and That Ain’t Good.” He said they had a beautiful arrangement in the key of G, which was her key. The band got it hot, and she did too. When Mary Ann finished, Ray looked surprised and said, “Come here, Little Sister. I liked that. I liked it a lot.” There was electricity in the air, so Mary Ann stayed until the end of the show, sensing a chemistry between them.

Later that evening, Mary Ann went back to Louisville with Ray and the band. She felt like a movie queen when they rolled out the red carpet at the Top Hat when they saw them arrive together. The most memorable part of the night was when they had a quiet moment together. He said, “I’m leaving town tomorrow, but I’ll be back in May, and I want you to be ready to go on the road with me.” Mary Ann’s heart jumped, and she felt lightheaded in the cab on her way back home.

When she told her friends what Ray had promised, they were skeptical, sometimes saying, “You can’t believe everything people tell you. I wouldn’t hold your breath for Ray to come back for you.” After a while, she stopped telling people, because their responses made her angry, but she really believed he was coming back to get her. She kept herself busy and continued to keep Ray in the back of her mind.

During that time, when Dave Morgan and his wife were visiting in Chicago, they saw Ray at a concert. After the show, Dave asked Ray if he remembered Mary Ann. His face lit up and said, “Tell that Black girl in Louisville that I’ll be back for her, and I’ve written a song, ‘Mary Ann,’ about her.” Mary was delighted when she heard the news.