The sign that demonstrators placed in front of Revelry Boutique + Gallery in late July said: “Fire! Fire! Gentrifier!” They had targeted Revelry because they claimed the shop had undermined their NuLu Occupation protest and was not doing enough to make their gallery and the commercial district more inclusive of Black people.

“Was very disappointed to find out that the owner is a performative ally,” wrote one reviewer on Revelry’s Facebook page. “... sad. once a customer, never again.”

It all started with a surprise demonstration on July 24 that shut down an entire block of Market Street in NuLu for around two hours and included demonstrators releasing a list of nine demands and a contract for neighborhood businesses and nonprofits to sign. Their goals included that businesses hire more Black people, carry more items from Black vendors (for retail locations) and work in other ways to make NuLu more hospitable to Black people. They claimed that NuLu businesses have benefited from gentrification started by the demolition of a nearby housing project in the 2000s, displacing its majority Black residents.

And they warned that if businesses did not comply, they would face social media shaming, boycotts, protest and more. (Protesters have since dropped the repercussions and softened the demands.)

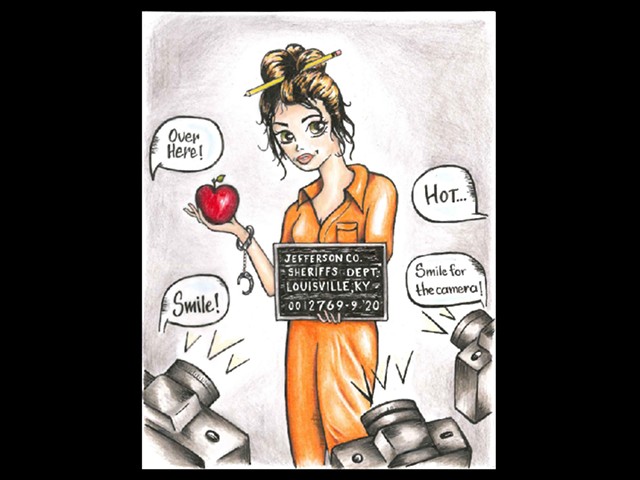

Louisville police arrested 76 at the demonstration, but in the hours and days after, protesters lambasted Revelry online, making allegations including that the owner had warned police about the occupation. The gallery has publicly denied this claim. The “Fire! Fire! Gentrifier!” sign outside of Revelry had been used at an earlier protest against the mayor.

Some NuLu businesses fought back, asserting that the protesters had no right to issue demands. One called it “bullying,” and at least one other compared protesters’ tactics to the Mafia’s.

But, their strategy seemed to work.

Protesters have succeeded in securing changes that even some detractors agree were needed to diversify NuLu.

Six businesses and one nonprofit signed the contract, now called a pledge, according to a new Facebook page identified as the Concerned Citizens of Louisville, a collective that is making sure the demands are met. There are roughly 150 businesses in NuLu. Some that haven’t signed the pledge still are making changes to diversify the commercial district.

Two weeks after the protest, at a “Lou Biz Talk” with Councilman-elect Jecorey Arthur and other District 4 businesses, Revelry owner Mo McKnight Howe said, “It’s been a very uncomfortable past couple of weeks for me. But, I am learning, and I’m actually excited to do the work.”

McKnight Howe declined an interview with LEO, and she has not signed the pledge. But at the Lou Biz Talk, she said that she had booked two solo shows for Black artists since the protests. And, on Facebook, she posted that the gallery is working on several diversity goals, including finding Black employees (the store has had Black employees in the past but didn’t at the time of the protests), adding more Black artists, implementing the diversity training asked for by protesters, and working “beyond the walls” of the store to “ensure Black artists and business owners are represented in this neighborhood.”

And, the NuLu Business Association has announced its own diversity initiatives. It has recruited a Black business owner, André Wilson of Style Icon, to head a NuLu Diversity Empowerment Council that will work to attract new Black and minority businesses, conduct education and diversity training, and partner with local colleges to recruit Black employees for NuLu businesses. Association members have also pledged $20,000 to a Black business incubator. The president of the Business Association, Rick Murphy, said that the diversity council was already in the works before the NuLu protest, although the Association did gather ideas for the council’s goals from protester demands.

Talesha Wilson, who organized the NuLu occupation, told LEO that protesters issued demands, rather than ask nicely, for a reason.

“We’re saying we demand this to happen, because if we don’t demand it, then it won’t happen,” said Wilson, who is now a part of Concerned Citizens of Louisville. “ ... When we say demands, we’re saying we’re taking back something that was already taken. So we can’t use the tone of, ‘Hey, can you please give me back my shirt from my house?’ Why would I be asking for something that was already ours — that was already ours at one point.”

Wilson said, overall, she considers Concerned Citizens’ campaign “really effective.”

A Facebook post announcing the businesses and the nonprofit that signed the Concerned Citizens pledge said, “These businesses and organizations are committed to doing the work of increasing Black representation in this gentrified neighborhood and have offered creative solutions aimed at doing so.”

The protesters’ tactics have not worked on everyone, however. At least one business that pushed back against protesters — La Bodeguita de Mima, a partially immigrant-owned NuLu restaurant — has yet to publicly announce any changes.

Why NuLu Businesses?

The protesters connect NuLu’s gentrification to the destruction of the Clarksdale public housing project that once stood on the border of the East Market commercial district, now called NuLu. The city replaced Clarksdale with the mixed-income Liberty Green housing development. In the application for funding, officials said that the project would “spur new economic development” in the area, according to a study called “The Other Side of Hope: Squandering Social Capital in Louisville’s HOPE VI.” The study was conducted by Rick Axtell, a professor of religion and college chaplain at Centre College, and Michelle Tooley, who was an associate professor of religion, and chair of the Peace and Social Justice Studies Department at Berea College, to assess the impact of the project.

Only 3.2% of the residents who lived in Clarksdale had returned to Liberty Green by 2010.

Three years after Clarksdale began to be demolished, Louisville entrepreneur Gill Holland started renovating his first NuLu building in 2007. He told LEO in an email that, as a former New Yorker used to diverse, urban environments, he was attracted to the area’s combination of “grit, locally-owned businesses and historic buildings, daily sirens, and walkability.”

At the time, the area was also home to Wayside Christian Mission. But, the homeless shelter moved, and Holland bought its buildings with other investors. (He said the homeless shelter is better off in its new location on Broadway).

Holland gave NuLu its name, and the area has become trendy, with restaurants, a hotel and shops, including several LGBTQ-, women- and minority-owned businesses but few Black ones.

Holland, who has been referred to as the Godfather of NuLu, said that protesters’ demands for more racial diversity make sense for the commercial district and for neighborhoods and organizations across Louisville.

“We as a city are missing out on tons of human potential because of structural racism,” he said. “So, I see a great opportunity for NuLu to lead in this area and in addition to being the most walkable local food, local arts and products, sustainable district, also be the most anti-racist neighborhood in Kentucky.”

The protesters did not name developers and property owners such as Holland in their demands. But, since the protest, he has started offering free rent to two different Black-led groups.

‘It was economic greed’

A letter to NuLu organizations from the Concerned Citizens of Louisville claims that the businesses of NuLu caused destruction to low-income communities, particularly those with Black residents.

“The policies and processes of the revitalization of NuLu has displaced marginalized people from homes their families have often resided [in] for generations, single-handedly progressing the gentrification of Black neighborhoods.”

Wilson acknowledged that NuLu businesses did not kick off the demolition of Clarksdale (that was the city), but she said they have benefited.

“So, no, you may not be the key investor, but you are a beneficiary of the key investor and what they do,” said Wilson. “So by us asking assistance, you also hold your leadership accountable.”

Murphy, president of the NuLu Business Association, told LEO that it is true that the commercial district is not diverse enough. It has only one Black co-owned member business, but three more fully Black-owned businesses are looking to open soon.

Still, Murphy thinks protesters’ recounting of NuLu’s history has left out key details. According to Courier Journal articles from 1996 that he sent LEO, another Louisvillian, Barbara Smith and local businesses were already working to revitalize the corridor at the time. The area was already home to art galleries, Joe Ley’s Antiques and Muth’s Candies, too.

Murphy said he’s not sure if the replacement of Clarksdale helped or hurt what would become NuLu. The displacement of Clarksdale’s residents, he said, was unfair, and reparations “probably need to be made.” But, he thinks they should come from government officials and the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. “We had no influence there,” said Murphy.

The Rev. Cindy Weber was not a Clarksdale resident, but she co-founded the Citizens of Clarksdale United, a group of Clarksdale residents who campaigned to ensure that they could return to the neighborhood after the housing development was replaced. She said she supports the Black Lives Matter movement, but she also believes NuLu businesses are not to blame for the replacement of Clarksdale.

“It was the city of Louisville that screwed over the city of Clarksdale,” said Weber, who is pastor of Jeff Street Baptist Community, near NuLu. “And they did it with the idea of — it was economic greed.”

And, it wasn’t just NuLu businesses that have benefited from Clarksdale’s demolition, Weber said: nearby medical centers have, too. In the “The Other Side of Hope” study, the authors noted that, “Encircled by the University of Louisville Medical Center, Jewish Hospital, Louisville Slugger Field, Waterfront Park, and the East Market business corridor, Clarksdale’s continued existence would endanger further economic potential of the area.”

Weber knew many Clarksdale residents and has seen how the loss of their home harmed them. Marvin Finn, a local artist whose “Flock of Finns” can be seen in Waterfront Park, was one of them. The city moved him to Beecher Terrace, another public housing project, after Clarksdale was torn down. The people who used to take care of him at his old home no longer lived near him. The same happened to another resident, Minnie Powell. She had to move away from her neighbors who brought her food, Weber said. Finn and Powell died within a year of moving.

Some NuLu business owners agree that they have benefited from the demolition of Clarksdale. McKnight Howe of Revelry took responsibility during the Lou Biz Talk. And so has Angie Reed Garner, the owner of garner narrative contemporary art, which opened before Clarksdale’s demolition in 2003.

“It seems simply true that NuLu as a shopping, dining, vacation destination neighborhood has required gentrification,” Garner said in an email, later adding that, when her family sells their building, they’ll personally benefit from gentrification by getting more money for the studio than what they originally paid.

Garner has signed the Concerned Citizens of Louisville pledge. “The demands are perfectly reasonable equity targets and I am happy to comply,” she said. But, some businesses are resisting them.

Threats or reasonable requests?

The original nine demands given to NuLu businesses included that businesses employ 23% Black workers to match the percentage of Black people in the city’s population. Retail shops were told to maintain an inventory of 23% Black vendors or make a recurring monthly donation of 1.5% of net sales to local Black organizations. (The former demand has since changed.)

The loudest display of public dissent came from a NuLu business owner the week after the protests. Fernando Martinez, the Cuban-born co-owner of La Bodeguita de Mima, posted to Facebook: “There comes a time in life that you have to make an [sic] stand and you have to really prove your convictions and what you believe in,” he wrote.

In his post, which is no longer publicly viewable, Martinez accused the protesters of being “Marxists with mafia tactics.” Martinez co-owns several restaurants around town under the umbrella of Olé Hospitality Group. He fled the socialist Cuba for the United States via raft in the ‘90s.

“I didn’t escape tyranny to be intimidated by these people,” he said.

In addition to repercussions, protesters’ demands were accompanied by a separate effort to give out Social Justice Ratings to NuLu businesses in the protest area from a creative cooperative, Blacks Organizing Strategic Success, or BOSS, started by the local activist Phelix Crittenden.The ratings — A for ally, C for complicit and F for failed — are posted to BOSS' website and are based partially on how well businesses meet the Concerned Citizens of Louisville’s demands. Most businesses were given a C initially, Crittenden said in a message after this article was first published. But, the No. 1 factor in determining a business' grade was how they treated the Occupy NuLu protesters, Crittenden said.

La Bodeguita initially received an A from Crittenden because its employees aided demonstrators during the protest, said Crittenden.

But, La Bodeguita received an F after Martinez stopped his workers from helping, Crittenden said, and for all of Martinez's other actions since the protest.

La Bodeguita did close on Thursday because of the protest, according to The Courier Journal, citing a press release. The story did not identify the source of the release.

The release also said that on July 24 protesters warned La Bodedguita that the businesses would be “fucked with” if it didn’t display a Social Justice letter grade on its door.Crittenden said that Martinez fabricated claims that protesters threatened him the day of the NuLu Occupation.

Murphy said some member businesses have retained attorneys and contacted police and the FBI in response to the demands, which he said border on criminal syndication. He would not identify the businesses.

“I’m always open to meet with anybody and talk about things for anything,” Murphy said. “But, I don’t have, I don’t like demands being pressed on someone, particularly when they are accompanied by threats.”

Wilson waived off accusations of extortion.

“We don’t think nothing of it,” she said. “Honestly, we don’t put any attention to that. That is just another way for white people with money to keep that money to themselves, even though Black people are dying every day, even though Black people work hard, even though Black people used to live in this space.”

In a set of FAQs sent to businesses, the Concerned Citizens of Louisville explicitly deny the accusation of extortion: “We have not and will not make threats nor extort money or property from any businesses for personal gain. Our ‘List of Demands’ was intended as a wake-up call to local businesses to examine their role in the gentrification of the former Clarksdale housing complex, so they’ll institute changes to mitigate their role in that harm.”

Concerned Citizens cannot force NuLu businesses to reconcile with the past, the document reads. And, it is up to the individual businesses to change their practices and for consumers who will now “be in a better position to make informed decisions about the businesses they support.”

Demands are softened

In the days since the protest and presentation of the demands, the protesters have removed the threat of repercussions. It is now called a pledge, and some of the demands have been diluted.

The pledge sent to NuLu businesses along with the FAQ says that Concerned Citizens of Louisville will use social media to promote the businesses that have signed the pledge and to document their progress on meeting demands.

A Facebook page under the name Concerned Citizens of Louisville was created recently, and it outlines which businesses are cooperating.

Concerned Citizens’ documents do not say what the collective will do, if anything, about businesses that don’t sign.

Wilson said the collective changed protesters’ original language to address some businesses’ concerns.

“We wanted to listen, and our goal is to create inclusivity, not exclusionary issues,” she said. “We don’t want to exclude anyone.”

In the FAQs, Concerned Citizens of Louisville say that to “eliminate any undue claims of impropriety and unwanted scrutiny of Black charitable organizations,” the demands no longer include an option for retail businesses to donate 1.5% of their profits to Black organizations. The demands still keep the option for stores to stock a minimum of 23% of their inventory from Black retailers with an added alternative of seeking “out creative solutions aimed at lifting up and empowering Black Louisvillians.”

The demands still include a requirement for businesses to require staff “Diversity, Equity & Inclusion Training” led by “Black Womxn Leaders,” but Concerned Citizens removed a list of specific Black Womxn Leaders that it originally said businesses must choose from.

The seven organizations that have signed the new pledge are: Dollface Brows & Beauty, garner narrative, Mahonia, The Mayan Cafe, NoraeBar, Zephyr Gallery and St. John Center for Homeless Men.

Social Justice Ratings Remain

While Concerned Citizens of Louisville’s repercussions for businesses are gone, the Social Justice Ratings campaign for NuLu businesses continues.Crittenden said that they approved of the repercussions going away.

"...It left room for interpretation," Crittenden said. "And those against our presence used that as a way to play victim. Our intentions were never to threaten, but they were to create a conversation — which we’ve been beyond successful in doing."

The rating system should stay, Crittenden said, "to keep accountability on these businesses. So that they know we’re still watching and working towards this goal of inclusivity."

The Concerned Citizens' FAQ says that the BOSS organization is also a Concerned Citizen (every Louisville resident concerned with gentrification and oppression and working toward Black liberation is, according to the document). But, the Social Justice Ratings are not under control of the Concerned Citizens and any questions about ratings should be directed to the BOSS organization.

Crittenden said that the Ratings are also meant to hold members of the public accountable for where they spend their money. Eventually, Crittenden said, they would like to give ratings to the rest of NuLu's businesses and to Louisville's. The ratings will remain on the BOSS website, Crittenden said, but if businesses want to display their grade, they can. Business owners can always work to change their grades, too.

"There’s always hope," Crittenden said. "Life is a journey. It’s about growth and learning. That starts with accountability. Accepting that you might not have directly contributed to the problem, yet are indirectly benefiting is a huge start. I don’t believe in canceling anyone trying to authentically do better. That being said, those intentionally not trying to do the work or facilitate these conversations aren’t allies, so there’s not much wiggle room for them to grow because they see nothing wrong with their behavior."

No worse than a bad Yelp review

Zack Pennington, a co-owner of the recently opened NoraeBar karaoke bar in NuLu, said in an email that the changed demands might be a sign that the collective is “listening to feedback and that the conversation that they wanted to start has successfully begun.”

Pennington said he doesn’t believe the original set of demands qualified as extortion.

“I don’t, because the demands were requests to analyze and change your behavior in a way that benefits the community as a whole and not a specific company or person,” he wrote. “Was it extortion when workplace sexual harassment training became commonplace? Not to mention, the consequences of not meeting their demands were no greater than the consequences of negative Yelp reviews: bad publicity, less patronage, etc.”

Pennington said he is willingly complying with the demands.

Garner said she was horrified by claims that Concerned Citizens of Louisville’s demands were extortion.

“It is callous to the experience of former Clarksdale residents, Black Louisvillians who have been hit hardest by COVID and the instability of our economy, and the people who are fighting for justice in this city,” she said. “We don’t want to repeat what was done to Clarksdale residents. Meanwhile the equity tasks do not strike me as anything a person of good will would resist.”

While Concerned Citizens of Louisville’s repercussions for businesses are gone, the Social Justice Ratings campaign for NuLu businesses continues.

In the Concerned Citizens FAQ, the collective says that the BOSS organization is a Concerned Citizen (every Louisville resident concerned with gentrification and oppression and working toward Black liberation is, according to the document). But, the Social Justice Ratings are not under control of the Concerned Citizens and any questions about ratings should be directed to the BOSS organization.

Crittenden was asked to comment for this story before it published, but they did not do so.

La Bodeguita, meanwhile, has gained the support of other Black-led organizations in Louisville, including the Louisville chapter of the Revolutionary Black Panther Party.

At a rally in support of La Bodeguita, Ahamara Brewster, a general with the Party said, “If you want help from someone, there’s a way about doing it, you know, being diplomatic about it. But you don’t threaten anybody.”

Martinez has said that La Bodeguita employs a diverse group of people and donates money to charitable organizations. But, he has still yet to announce any efforts to specifically help the Black community or to further diversify NuLu.

‘They can do better’

André Wilson, the fashion designer and stylist behind Style Icon, has been working in NuLu for years. He takes clients to shop at NuLu boutiques, and he’s worked with RoxyNell.

“The people were always amazing to me, and they had a strong LGBTQIA representation. And it always had an artistic feel, always felt welcoming,” said Wilson. “But when you take a deeper look, you realize that there’s only a few Black businesses, they can do better. Just like so many other business communities can do better.”

Wilson was having this conversation in private with other businesses after the NuLu protest. He plans to move his business to NuLu soon, and now that he’s the chair of the NuLu Business Associations’ Diversity Empowerment Council, he said, he is ready to work to change the inequity he sees.

The NuLu protest reminded him of all the gains that Black people have made through similar demonstrations and unrest, he said. He didn’t like the repercussions that came with the demands, but he thought the demands were worth a conversation.

Already, two Black-owned businesses are set to open in NuLu in addition to Wilson’s: another Seafood Lady restaurant and a hair salon. Murphy said the Association began developing the council in June, but the protest and demands did impact the project.

“It made us address it a little more seriously and really look for some people that could help make change and give us better direction,” he said. They also influenced some of the goals of the diversity council.

The Association is not working with Concerned Citizens, because the collective isn’t transparent about who is involved, said Murphy. Talesha Wilson said businesses don’t have to work with her group. She just cares that the work is done and is transparent.

“They can do whatever they want to do, honestly,” she said, “as long as the goals get met. However, we think that it’s very important for them to be transparent and create some type of liaison between the community and the businesses.”

Murphy said that the NuLu Business Association hopes to work with other Black leaders in the community (not associated with Concerned Citizens) and to hold roundtable discussions.

Making it work IRL

For the NuLu businesses that have chosen to collaborate with Concerned Citizens, the collective is open to working with them if they can’t immediately meet the demands, which is important at a time when small businesses are struggling because of the pandemic.

Garner narrative doesn’t have employees, but it does have one Black artist booked for the eight solo shows the gallery has planned for the next two years — putting Garner’s Black representation at about 12.5% instead of the 23% it needs to be in compliance with Concerned Citizens’ demands.

To increase Black representation, Garner said she’ll probably have to start showing more artists she doesn’t personally represent and curate more two and three person shows, because her space is big and few artists have enough work to hold the space by themselves. She’s also looking for a Black-owned business to contract with soon for service work.

Garner said she could make progress on Concerned Citizen’s demands by an Aug.17 deadline that the collective gave.

NoraeBar’s staff is already almost 23% Black, according to Pennington. But, the prospect of stocking 23% of the bar’s inventory with products from Black-owned businesses initially seemed impossible. That was until one of NoraeBar’s bartenders started putting together a list of Black-owned spirits, beer and wine companies and coordinating with their local distributors. Now, the bar is making progress, Pennington said.

“The group [Concerned Citizens] seemed responsive to that concern and the feedback I’ve given has appeared to influence some of the responses in the FAQs document,” he said. “If you meet people with empathy and show through both actions and words that you’re willing to work together, most people are reasonable to work with.”

If the NuLu protesters hadn’t been as forceful with their original demands, Pennington said, he thinks NoraeBar would have still complied.

“But,” he said, “we might be the exception and not the rule.”