Go here to read excerpts from Black Scene, a cultural and political magazine published in The West End during the 1970s and now is being resurrected by local writers and photographers.

Rev. Leo Lesser Jr. is a name that is not widely recognized in Louisville, but his legacy is still being felt in the city. Lesser was the president of the Greater Louisville Area AME Ministerial Alliance in the late 1960s when he marched with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. to protest segregated housing. His work led the city of Louisville and Jefferson County to adopt Fair Housing ordinances.

In 1973, Lesser launched a mayoral campaign to bring further attention to Louisville’s Black community, which was still recovering from redlining, urban renewal and the 1968 Parkland Riot ignited by King’s death. Lesser was the first African American mayoral candidate in Louisville since 1921 when A.D. Porter Sr. ran on the Lincoln Independent Party ticket. Lesser put together a diverse coalition that included young Black activists including Shelby Lanier Jr., who would go on to file a lawsuit forcing the city to hire and promote more Black police officers, and white liberals such as attorney Robert Delahanty and his activist wife Dolores.

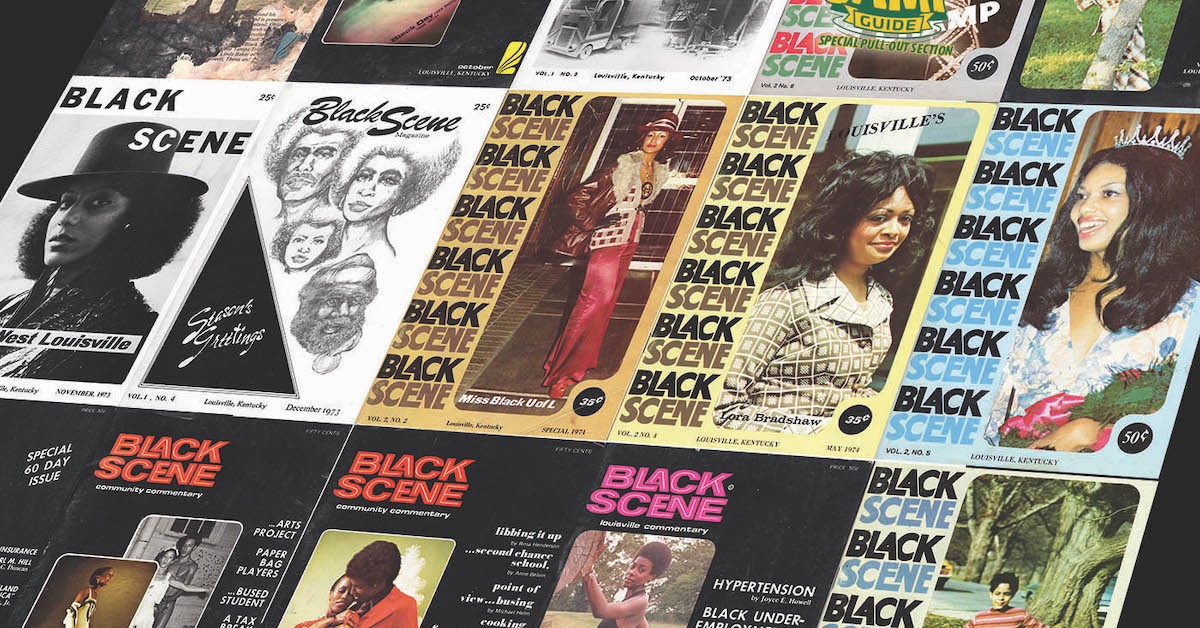

Many of Lesser’s supporters were disappointed with the treatment that he received from the media. Rather than take his issues seriously, he was accused of working for Harvey Sloane, another candidate, to draw Black votes from the Democratic frontrunner, Carroll Witten. After losing the primary to Sloane, Lesser and his supporters formed Black Scene, an African American, general-interest magazine like Jet, a national publication that moved from print to digital-only in 2014. Lesser became the editor of Black Scene, and Dr. C. Milton Young III was its publisher. Robert Delahanty stayed on as an associate editor until he became a judge.

Lesser said the goal of Black Scene was to “point out the achievements of black people that otherwise might be overlooked.” The magazine featured articles, art and commentary dealing with local and national issues that concerned African Americans in Louisville. The magazine had a weekly radio show on WFPL, sponsored local events and even produced television segments.

Lesser died in 1974. Young kept the magazine going for two more years with help from the community, including Johnny Johnson, who would one day lead the Kentucky Commission on Human Rights. The first iteration of Black Scene folded in 1976. One of the writers, Anita Nelam, resurrected the magazine in 1983, but it didn’t last more than a year.

Black Scene was nearly forgotten until Dolores Delahanty discovered 17 issues of the magazine in her basement. Dolores gave the issues to her granddaughter, artist Katy Delahanty, because she thought her grandfather’s radical youth might interest her. She planned to donate the magazines to a historical archive. However, after she started reading them, she realized Louisville was still dealing with many of the same problems that Lesser and his staff wrote about.

“Less than a decade after the Civil Rights movement, Louisville was in a period of transition that can still be felt rippling throughout the city today. From the years 1973 to 1976, a dedicated collec-tive of activists took it upon themselves to tell the story from their side of the city. The collective created a platform to showcase the literary and artistic talent in their community,” Katy Delahanty said. “The result was Black Scene — a self-pro-duced, published, distributed magazine, purchased for a quarter at local beauty salons, restaurants and newsstands. It was pocket-sized and beautiful, containing everything from inmate poetry to grandmother recipes.”

Delahanty contacted me because of my experience in journalism and history, with the goal of creating an updated version of the Black Scene. We decided to use the table of contents from the original magazine to publish a quarterly magazine called Black Scene Millennium for one year. The first issue of our publication is scheduled to be out in June, in time for Juneteenth. It will include the older articles with accompanying updates or similar takes on those issues.

After we finish publishing Black Scene Millennium, we plan to collect the new and old material into a coffee table book.

Said Delahanty: “The purpose of Black Scene Millennium is to constructively identify challenges that remain since the original publication, and to create an outlet for reflection on the city’s future.”

“Black Scene Millennium will adhere to the ‘70s aesthetic and use the original table of contents as a framework. At the same time, an advisory committee made up of past contributors, editors and current social justice activists evaluate content to be sure it aligns itself with the namesakes’ original intent. Focusing on The West End during this era of revitalization and the city’s youth, the magazine will make material relevant and intergenerational.”

The community reaction to the Black Scene Millennium project has been amazing.

Photographers Bud Dorsey and Eddie Davis, both contributors to the original Black Scene, have joined our staff.

The Black Community Development Corporation has agreed to serve as our fiscal sponsor.

Black Scene Millennium received the Fran Huettig Public Art Series Award, to create three large-scale murals. The Fran Huettig Award is a partnership between Fund for the Arts and 1619 Flux Art + Activism. The award of $20,000 will result in three murals of the original Black Scene covers around the city on buildings owned by New Directions. The first one was done in November by Charlie Nunn at 226 N. 17th St. on a building called the Roosevelt. The second one will be on a building in the Parkland neighborhood.

Also scheduled are several upcoming community events to talk about the project.

The Table Café, at 1800 Portland Ave., has invited us to do one of its Table Talks on March 10 at 6 p.m.

For more information on Black Scene Millennium or to get involved, please visit blackscene.org or email [email protected].