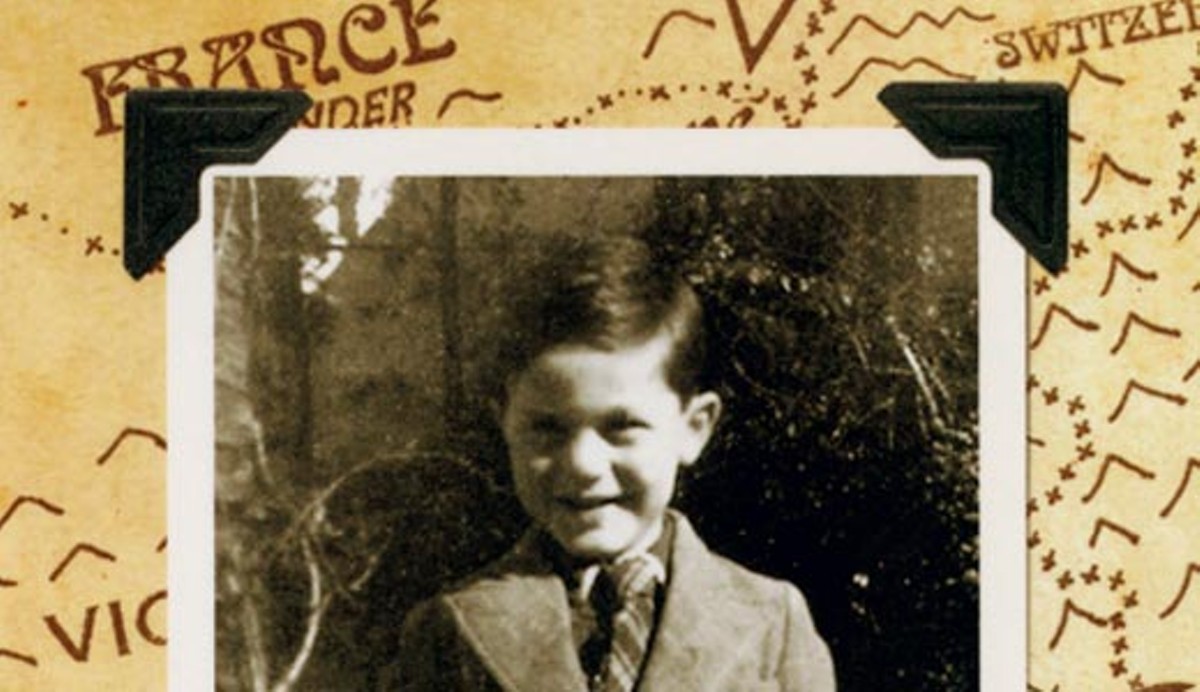

Fred Gross was only 3 years old when his family began running from the Nazis.

The journey started at dawn on May 10, 1940, when a series of thunderous booms jarred the Gross family awake inside their apartment in Antwerp, Belgium.

High above clouds of black smoke, German fighter planes circled, unleashing an arsenal on the north Belgian city, which until that day had remained safe for Jews during World War II.

The family spent the next three days packing whatever they could carry and devising an exit strategy, a difficult task given they did not own a car and the trains were all filled with soldiers bound for war.

They finally found a taxi driver willing to drop them a few hours away at the French border, where thousands of other refugees desperately searched for safety.

Fred Gross — along with his mother, father and two older brothers — would spend the next two years eluding the Nazis, a dangerous expedition he did not fully understand until years later.

“My memories began quite early, but the stories of my mother and two brothers helped fill in the gaps,” says Gross, of Louisville, who recently published a book chronicling his family’s flight. “I remember clearly walking and hiding in the middle of the night. I remember being with a family who hid us out for several weeks. Those memories are very vivid, but the heart of the book is the interviews.”

Sitting inside a local coffee shop, Gross, 72, recalls the first time he considered delving into his family’s history: While honeymooning in Europe nearly 25 years ago, Gross and his wife, Carolyn, met his two brothers in Belgium. As the group dined at a local café, Carolyn asked about the family’s flight from the Nazis, something the brothers had rarely discussed over the years.

“That was how it all started,” recalls Gross. “In the mid to late 1980s, people were really just beginning to tell their stories from the Holocaust. But because I was so young at the time, I would need help telling our story.”

Then a reporter for a daily newspaper in Connecticut, Gross had little time to embark on a personal writing project. But over the next four years he began gathering information, conducting interviews with his mother and brothers (his father died in 1973).

In 1990, Gross and his wife moved to Louisville to be closer to her family. The longtime reporter left journalism, taking a public relations job working for several local school districts outside Jefferson County.

It would be nearly two decades before Gross completed his book. Several editors initially rejected the work, a combination of his own memories, made complete with the stories of his family. One editor actually suggested he alter the narrative and market the book as fiction, a notion he found absurd.

“The one big reason I wrote this was so I could come to terms and come to peace with my childhood,” says Gross. “I also wrote it for those who didn’t make it out, especially the children who lost their lives.”

Three days after German troops invaded Belgium, the Gross family pooled resources with another refugee family they met near the border and bought a used car. They traveled into France, sleeping in bed-and-breakfasts whenever possible. If there were no rooms, Gross recalls sleeping wherever they could — a movie theater, old barns, a school auditorium.

Within weeks the car broke down and they were forced to hitchhike.

“The German army was advancing toward us; at one point they were maybe 45 miles away,” he says. “They continued bombing the area. There were villages burning and people dying. I did not remember that, but my brothers told me.”

France surrendered to Germany in June 1940. Soon after, French police began ordering Jews — including the Gross family — to board busses. “They told us that they were taking us to another village where we would be free,” says Gross. “Instead, they took us to an internment camp.”

The war still was in its early stages and at that point, anyone housed at the internment camp was permitted to leave as long as they had paperwork proving a French citizen would house them. While at the camp, Gross’s oldest brother escaped for long enough to convince a sympathetic citizen to take in his family.

“Unfortunately, many of the people who did not get out of that internment camp were deported to Auschwitz,” he says.

As France became increasingly dangerous, the family remained on the move, ultimately settling in the French Riviera.

They checked into the Hotel Continental, where they lived for the next year and a half. Gross says his father — a jeweler — paid for the room by selling diamonds on the black market.

The hotel was home until the summer of 1942, when they learned Nazis were coming in droves to arrest any Jews in the area. Gross says his father convinced a Catholic man he gambled with to hide them in his family’s home, where they remained for six weeks.

Finally, they obtained fake passports and fled to Switzerland, neutral territory where they lived until the end of the war, before immigrating to New York City.

After recounting his childhood odyssey, Gross sits back in his chair and, for the first time during the conversation, his voice cracks as he says, “What humans can do to each other … even animals don’t treat each other that way.”

When the book first was published, he says there was no joy for him, at least not at first: “I just felt sorry for those who didn’t make it out.”

But, he adds, “Hopefully readers are able to understand there are two choices in life: One is to be like that Catholic family that took us in. The other is to stand on the sidelines and do nothing.”

Book Signing

Fred Gross will sign copies of his book, “One Step Ahead of Hitler: A Jewish Child’s Journey Through France,” at 7 p.m. Monday, May 18.

The signing will take place at the Barnes & Noble at The Summit, 4100 Summit Plaza Drive. Call 327-0410 for more details.