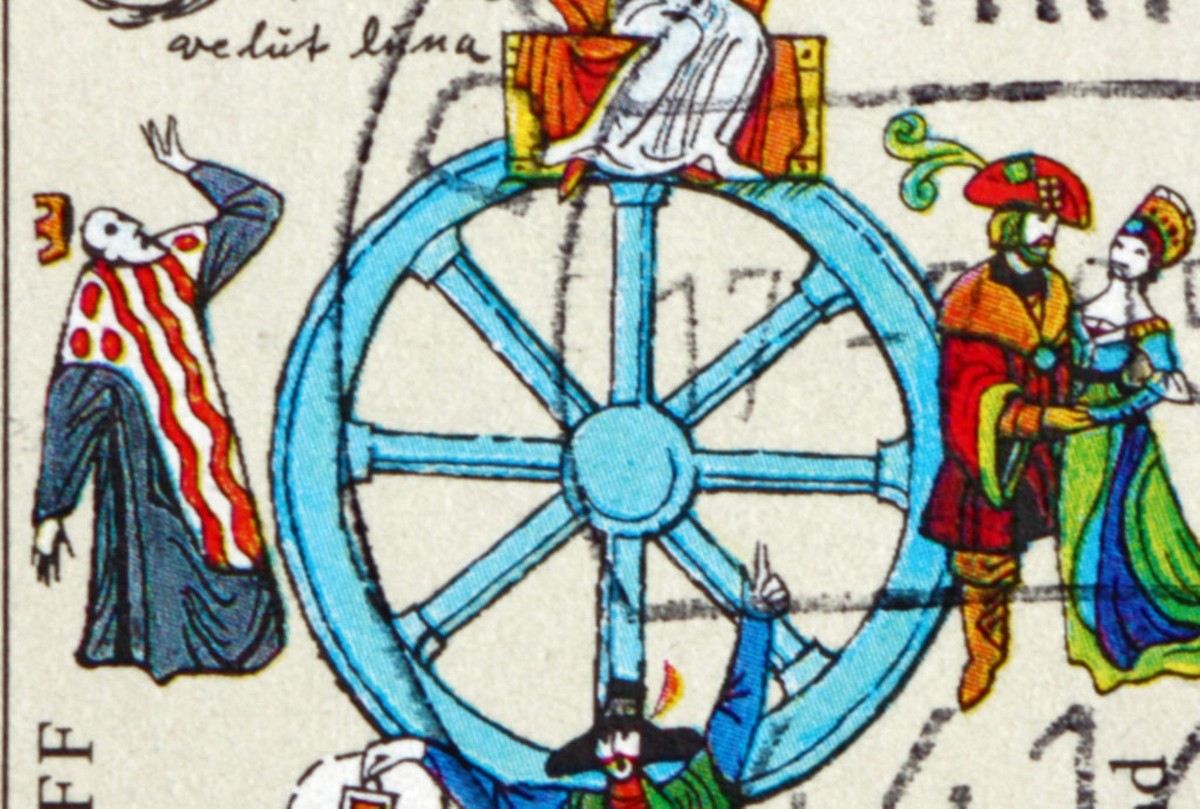

Lately, I’ve been losing myself in the sumptuous music of Carmina Burana, a cantata that sets medieval monks’ poems about destiny, sex and alcohol to epic, powerful arrangements like “O Fortuna,” “Were diu werlt alle min,” and my personal favorite, “Tempus est iocundum.” The composer, Carl Orff, wrote the music in the 1930s and 40s, but the best pieces have had serious staying power (in pop culture and elsewhere) throughout the last century.

A 2006 NPR piece about Carmina Burana described it as being full of “extremes and excess.” Outside of LEO, I make a living in theater photography, the intersection of two art forms that make melodrama out of everyday life. “Extremes and excess” are my career, yet so much of 2020 neutered me into a life at home, without theater. Daily, I saw the same dusty laundry room. The same backyard. The same neighbors’ cars. The same wooden floor onto which light spilled, not from the lofty rafters, but from the fridge. It was a struggle to get through a photo class doing staged “performance” photography at home last spring because I knew that it just wasn’t real. It wasn’t right.

But rediscovering Carmina Burana through the Munich Percussion Ensemble’s 2017 performance has reawoken my motivation for my work — because that’s exactly what my favorite part of it, “Tempus est iocundum,” does. Everything about this piece just works.

Those opening notes — the high-pitched women’s voices in sync with the tambourine — set up the rest of the piece so beautifully and brightly. Each “quo pereo!” is a burst of pure joy. Even the way that the baritone soloist glances at his female counterpart gives us the sense that we’re not just an audience to a song, but to two characters in their own scene.

The best part, though, is that gorgeous, weighty “totus floreo,” which means “I am wholly blooming.” In this concert hall — stately and high-walled, yet warm and earthy like a medieval tavern — the phrase rings so beautifully that I am tempted to tattoo it onto my arm.

But I am not wholly blooming. I am still living at home. I am still working through the aftershocks of the pandemic: the betrayal when one of my closest friends turned into an anti-masker. The panic when he suddenly got sick. The loss of income when my summer job was canceled last-minute because of COVID. The loss of faith in my government to prevent something like this from happening.

For what it’s worth, not every song in Carmina Burana is equally capable of being a necessary distraction. “Were diu werlt alle min,” a song about forsaking the world to romance the Queen of England, conjures up images of imperial triumph and victory in only 56 thunderous seconds. But its counterpart, the jarring “Ego sum abbas,” is less a transporting piece of music and more a depressing monologue with an occasional interjection from the percussionists. It’s just uncomfortable. That’s not to blame the performers, by any means; the musicians are skilled and the baritone soloist, Carl Rumstadt, has a powerhouse of a voice. A listener will take to it better, though, in pieces like “Circa mea pectora,” in which the swells of the orchestra and the male chorus back up the singer as he moves toward his ultimate decision, punctuated by the quick notes from the women that imply an anxious internal dilemma. It’s the most beautiful, longing ode about a man cheating on his girlfriend that the classical music world has to offer.

Two of the first pieces in Carmina Burana that I ever listened to were “Veni, veni, venias” and “Floret silva nobilis” in high school. I didn’t know the full meaning of either song; I knew that “veni” was encouraging something to come forth, and I assumed “floret” meant something to do with plants growing. Musically, they were both bouncy and sprightly, so, in my head, they both had the same approximate meaning: please come, spring! A great sentiment in any year. But in this particular year, when we’re dependent on what spring can offer — the vaccine, the opportunity to get outdoors, to be safe and warm and amongst friends — that message is even more urgent. Listening to those songs — even knowing now that their meanings are definitely not what I had thought they were — almost feels like I am sending up a plea to Fortuna, destiny, herself.

The poems that make up the text of Carmina Burana predate the Black Plague, but we and the people of the medieval age share the same love of theatrics, of excess, of extremes. It’s stayed with our species through the ages. We want to get together in person and feel the soaring glory of a chorus hitting a high note — or a “totus floreo” — deep in our souls. We just don’t want to worry that doing so might threaten the lives of our loved ones.

Through the last few months of winter, getting lost in Carmina Burana has been my method of self-preservation, a way of reminding myself that beautiful performances like this one will return to the world. There will be shows again. There will be actors, there will be lights, there will be songs. This year and next, the performing arts and I will, once again, bloom.