‘The Underground Railroad’ by Colson Whitehead (Doubleday; 309 pgs., $26.95)

This novel comes with plenty of positive notice. An Oprah Book Club selection. A National Book Award winner. An even fuller blossoming of talent from a fellow of the MacArthur and Guggenheim foundations.

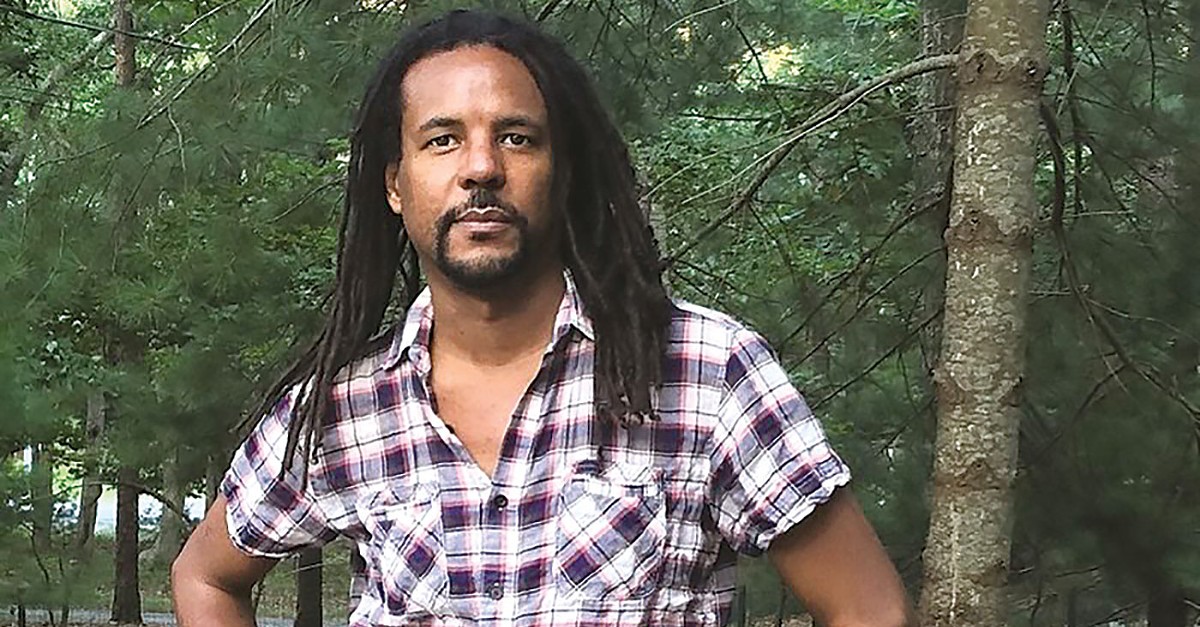

So how does Colson Whitehead’s book stand apart? It’s shot through with both magic-realism and tersely soul-bludgeoning realism. A history of family, community and institutions — during which the quest for freedom points to the future, loaded with a freight of irony and satire. That latter pairing might just make for an approach that’s as healthy as the expected blend of hope, courage and desperation to be expected from a work of this title. Louisvillians have the chance to see how the author developed his themes, characters and allegorical tableau when Whitehead is interviewed at The Kentucky Center’s Bomhard Theater.

Whitehead will be interviewed by Isaac Fitzgerald, editor of BuzzFeed Books. Because the event has proved a popular ticket, The Kentucky Center is accommodating a larger audience by offering a live screening of the interview/reading at its North Lobby.

For now, read the book.

Cora, introduced as a third-generation slave of the antebellum South’s cotton plantations, is a resourceful survivor who makes and shares sharp observations. But as much as she resembles other indelible characters from the likes of Toni Morrison and Alice Walker, we also have to look at Cora in terms of Swift’s “Gulliver’s Travels” — because the journey north toward freedom is riddled with traps-in-waiting and elaborate broken promises. Whitehead breaks these set pieces from any musty bonds of far-removed history by turning the metaphorical railroad that helped free runaway slaves into a real transit system. Like many a 19th-century technological marvel, it brings people into new situations that seem to open up a brighter future. The story breaks wide open as Cora enters a South Carolina that seems like an enlightened society, but with hints of “The Twilight Zone.” Other states and railroad stops have their own unique twists.

Along the way, Cora has a slave hunter at her back: Ridgeway, a monster of twisted self-justification (“The American imperative is a splendid thing…”). Personal legacy also dogs Cora: She’s the daughter of a runaway. Whitehead builds narrative power through the mother: She has sections as protagonist, but they’re painfully brief, deepening the sense of the pitilessness of American slavery by showing its machinery turning human lives into fodder. Our understanding of the many sides of Cora is likewise strengthened by this fleeting shadow-narrative. (Seeing her mother in a dream as “Begging in the gutter, a broken old woman bent into the sum of her mistakes.”)

The most important question regarding this novel might be whether the magic realism is a distraction that throws off appreciation for the grit and suspense. The answer lies within the tolerances of the individual reader. The author is refining motifs and devices (for example, machines of transportation make for demanding means of transformation) encountered in his imaginative first novel, “The Intuitionist.” Anyone who can’t suspend disbelief for Gabriel Garcia Marquez or Isabel Allende might indeed flinch as soon as they see the word “skyscraper” after getting settled into a tale of the early 19th century. But the rest of us should remember that this is the modern master who, not long ago, delivered “Zone One,” the most literate zombie novel ever (Sorry, Joyce Carol Oates!). It’s a bibliophile’s dose of pure excitement to watch the continuing arc of Whitehead’s career and wonder if there’s anything he can’t do.