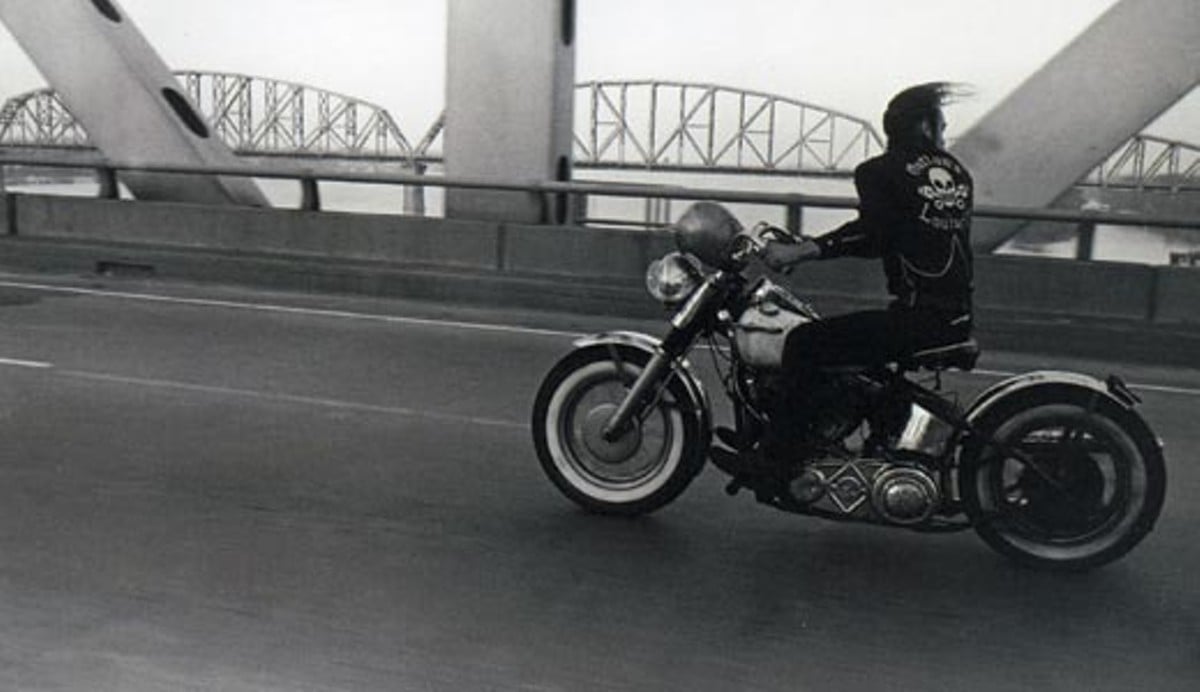

An old adage warns against judging a book by its cover, but in the case of Kentuckian Brett Eugene Ralph’s debut book of poetry, “Black Sabbatical,” the cover is a direct representation of the writer’s vision. It is stark black with limited text; in between the title and his name, there is a photo by famed photographer Danny Lyon entitled, “Crossing the Ohio,” in which a member of the Louisville Outlaws is riding a motorcycle across the bridge. The man is looking over his shoulder while careening forward on his bike, seemingly alone on an empty road.

“That’s a great metaphor for poetry,” Ralph says across a table on the patio of Highland Coffee on a recent Friday afternoon. “He’s speeding forward and looking back.”

Throughout his life, Ralph has blurred the lines of many a stereotype, always moving forward but still relying on past experiences; he has been a poet, a punk rocker, an academic and a football player — labels that rarely, if ever, coincide.

“I’ve always bristled against being defined,” says Ralph, his own appearance an example of this. Ralph is a mid-sized man with a shaved head and a medium-length beard. He sports candy apple red Converse sneakers and a necklace depicting a religious idol. “It was almost pathological when I was younger. I played football, I graduated third in my class; I sang in this punk rock band, did every drug I could get my hands on. I wanted to go in all these directions at once, because it all interested me. And I really hated being defined as a jock, or a brain, or a punk, or whatever. If you’d start talking about punk rock, I would emphasize my football side, because punks hate jocks. I always wanted to be defined by my exception to the group I was in, and that’s just adolescence and vanity.”

He began writing poems when he was 7 years old, and can recite verbatim the first poem he ever wrote, about a red-and-blue rainbow with “colors bold and bright,” declaring it a “pretty sight.” In high school, he became simultaneously involved with music and poetry, and credits punk rock — his first band was hardcore act Malignant Growth — with helping establish him as an artist. He says punk helped him to maintain his “macho” image and served as a masculine transition into more calm and subtle modes of creative expression.

“Punk rock was just my way in the door to being an artist,” he says. “Where I come from, people didn’t make art. Punk rock was a macho way. Because before punk rock, it was like, football, punk rock and then poetry. And so punk rock was a way to start reinventing myself as an artist, but to be still macho enough and related enough to what I’d been previously.”

Though still involved in music (Brett Eugene Ralph’s Kentucky Chrome Revue), Ralph has become a well-established poet. His work has appeared in The American Poetry Review, The Stiffest of the Corpse: An Exquisite Corpse Reader and McSweeney’s Book of Poets Picking Poets.

Local independent press Sarabande Books chose “Black Sabbatical” for the 2007 Linda Bruckheimer Series in Kentucky Literature, an annual contest that focuses on the work of a Bluegrass writer. The book features 28 poems, and he considers it to be something of a greatest hits collection, as it spans nearly 20 years.

Ralph writes in clear, concise lines, little models of conveyance that also spare some ambiguity.

“I aspire to create poems that approximate the complexity of experience, that aren’t just reduced,” he says. “Most truly popular art, like pop music, its shelf life is diminished by its willingness to reduce the complexity of the world to a simple sound byte or to one feeling, or to one thing. We’re never just feeling one thing.”

Ralph’s poetry connects with the world around him, from tangible objects to arbitrary experiences. “Emaciated Buddha” was inspired by a tiny bronze Buddha statue at an exhibit in New York:

Like Christ in Grünewald’s triptych,

he looks like a man who’s truly spent

a lifetime nailed to a shadeless tree:

skinny arms like tired entreaties,

face like a cave, each protruded rib

a distinct refusal, once and future

beauty of the body discarded

like a murky early draft.

“It really moved me,” he says of the statue. “I really just kind of felt the gravity of how hard he tried and how much he risked to get to the level of insight he got to.”

Another poem, “Only Child,” was written during a drug-fueled inquiry into whether he, an adopted only child, could have a twin somewhere out there. “Firm Against the Pattern,” which opens the book, went through a revision that Ralph believes set the tone for the entire collection. The last two lines lament “all those desperate gestures/we collect and call the seasons,” the word desperate having been changed from delicate.

“In a way, the idea of desperate gestures is less interesting to me than delicate gestures, but guess what?” he says. “This whole book is about desperate gestures that people make trying to live and understand themselves and their lives. And that ended up being the perfect introduction for this book in a way that delicate gestures wouldn’t have been. There’s not a whole lot of delicacy in this book.”

Brett Eugene Ralph reading from “Black Sabbatical”

with music by Catherine Irwin to follow

Saturday, July 18

The Lounge

947 E. Madison St.

458-4028

Free; 8 p.m.; 21+