Black Hole Blues

By Patrick Wensink. Eraserhead Press; 196 pgs., $10.95.

A world with Kenny Rogers is a strange world. Take, for example, an episode of “The Muppet Show” in which then-superstar Rogers sings “The Gambler” — or rather, shares the vocals — aboard a train car with a grotesquerie of wizened human figures, one of whom he offers a cigarette. Perfect fare for the children of Generation X, obviously. Not to be outdone, Rogers sings the final verse with his characteristic tenor, to which the elder Muppet responds first by dying, then by leaving his body as a dancing, jeering ghost. Bizarre.

None of this, surreal as it is, comes close to the absurdity in Patrick Wensink’s second novel, “Black Hole Blues.” He also wrote “Sex Dungeon for Sale,” so what do you expect?

The premise is, on some level, simple: Fading country music star J. Clause Caruthers is immersed in your typical existential nightmare. He has weighted himself down with a nearly insurmountable task: writing a country song for every woman’s name, which he has done but for one — the letter Z. This happens against a backdrop of extreme competition with one Denny Dynasty, a bejeweled gay singer who is attempting to steal the limelight by making a song for every man’s name. In the midst of all this, Caruthers has become, after leaving liquor behind, an aficionado (or addict) of club sandwiches, tasty morsels crafted specifically by Jesus, his disgruntled tour bus cook.

Have I mentioned Caruthers has a brother? A twin brother, no less, named Lloyd, who has created a black hole in his laboratory in a race to be as good as his hero, Einstein, whom he is shorter than by a number of inches. There are family problems: The brothers do not speak. There is also a sister, Zygmut, who has vanished and suddenly reappears, in noir fashion, on the scene. Of course, her name is the final name in the alphabet song-cycle, and the one Caruthers must craft into a song to overcome the memory of that terrible thing he did to an elderly woman in Missoula, Mont.

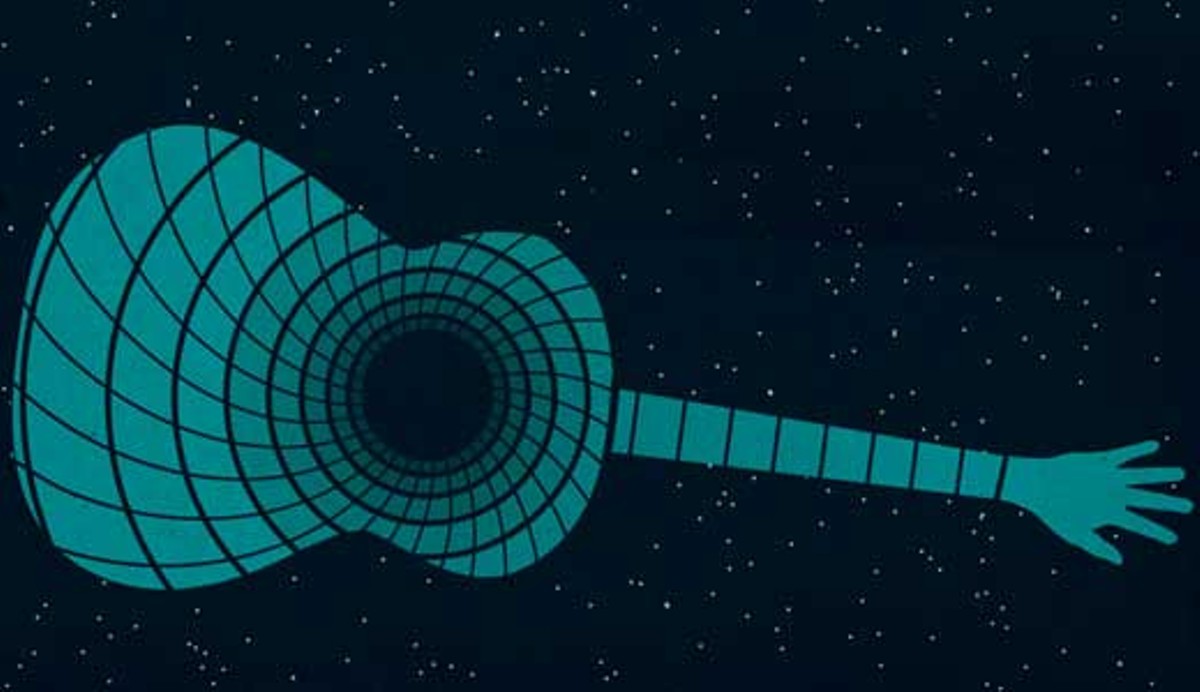

You can’t fault “Black Hole Blues” for its ambitious characterization. Which is to say, everything is a character: Rusty, the guitar that insists on going out of tune; the purple tour bus; the overly excitable proton; the patient and self-satisfied black hole; and the purpling, rotting sandwich lost beneath the bed that wants only the fulfillment of having but one single bite taken from its body. And then there’s Kenny Rogers, who is worked into the plot as a kind of foil to Caruthers, here known as “Nashville’s Shakespeare.”

This is, by any measure, an outrageous book. Readers who delight in the wild flips of imagination will find an undeniable “Da Vinci Code” of pop art postmodernism in “Black Hole Blues.” Which is not to say it has no substance: Lurking at the heart of the novel is a dark underbelly of death and identity. Among other things, Wensink sinks his teeth into the conventions of dialogue and the interior monologue to round each character into their individual assemblages of anxieties and failures. Each of the brothers, in their own way, opens the door to their personal and collective annihilation. The real black hole here is the yawning realization of intractable loneliness.

Wensink is hosting a reading and signing party for “Black Hole Blues” on Saturday, June 4, at The Bard’s Town, 1801 Bardstown Road, at 9 p.m. The night will feature a DJ and “Death to Kenny Rogers — The Game Show.”