It would be easy to demonize the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development for its recent funding cuts to transitional housing programs for the homeless.

Just consider the heartbreaking stories about who will be affected.

Single mothers. Men with HIV. Kids who have witnessed domestic abuse. Drug addicts. All with no homes and little security, and now with fewer options after the announcement.

Locally, $1.2 million in grants vanished from eight nonprofit agencies helping more than 1,000 of the region’s most vulnerable.

Once the checks stop, these providers will have to fight each other for private sources of money, or they will close.

And frankly, it stinks.

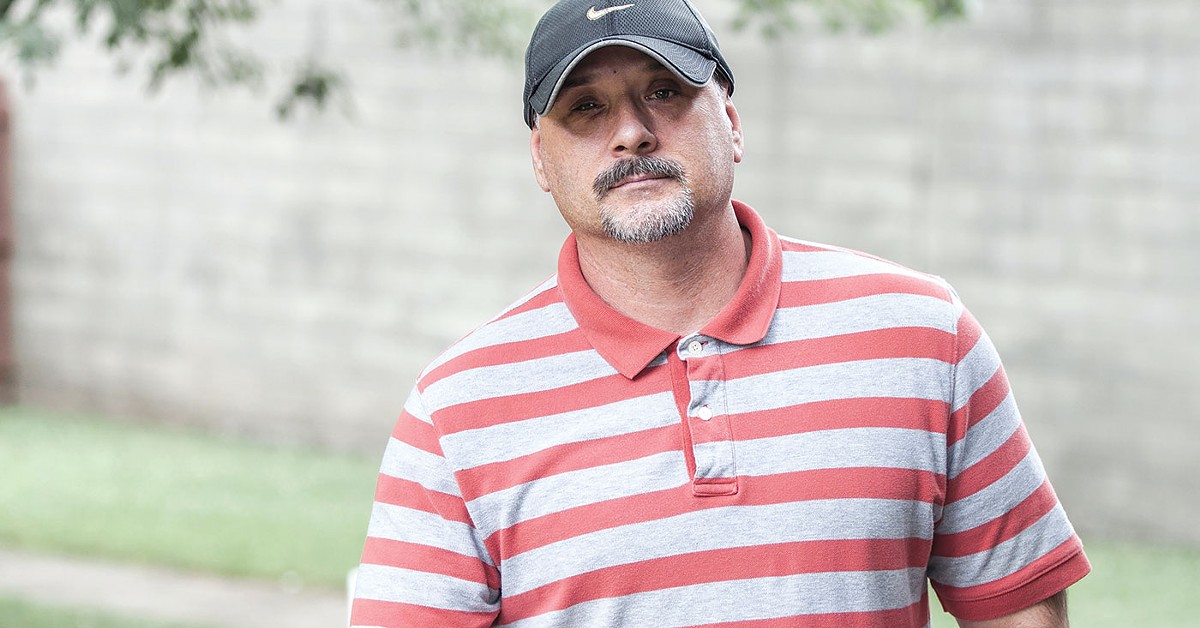

“This isn’t all about the data,” said Brian Thornton, 50, a resident at Glade House, a transitional housing facility run by House of Ruth, which will lose roughly 70 percent of its funding under the cuts Aug. 31. “We’re talking about human lives here.”

But agency spokesman Brian Sullivan said HUD is not abandoning Thornton and other homeless people. It has rethought how it handles them, now giving preference for funding to those organizations that follow its Housing First strategy, which focuses on providing permanent housing as fast as possible, rather than transitional housing. Once they have a roof over their head, then supporting services to help them stay in that home can be obtained, he said.

Of course, other agencies — not HUD — will have to foot the bill for additional assistance such as counseling, drug and alcohol rehabilitation, some of the issues that put them on the streets in the first place. And such services are not mandatory as they are in some transitional housing programs. That is left up to the client and other agencies to negotiate.

“It’s no longer enough to manage homelessness,” Sullivan said. “We’ve got to end it. And so it’s a huge challenge, but it’s a challenge for all of us. And we’ve tried to communicate that challenge to everybody as openly, and as loudly and as frequently as we can.”

The shift comes because the agency has been forced to make do with less money from Congress. Housing First just so happens to also be the cheapest path, and some studies show it can work.

Critics are dubious, however, saying that immediate, permanent housing does not work for all homeless people because some still need to be steered into services before they can move out on their own. With no safety net in place, individuals helped by the transitional method may be forgotten in both housing and supportive services, and find themselves back in precarious situations.

And then there is the issue of lack of affordable housing in Louisville.

“We don’t have enough affordable housing. So when you don’t have enough affordable housing resources, you can’t put everyone directly into permanent housing,” said Catherine McGeeney, the director of development for Louisville’s Coalition for the Homeless. “You need transitional programs.”

U.S. Rep. John Yarmuth, D-Louisville, blamed the shift on Republicans who control Congress and refuse to increase HUD spending to truly take care of homelessness.

“HUD is having to meet more demand with fewer resources. That’s the overriding dynamic that’s going on,” Yarmuth told LEO. “Clearly the refusal to fund these programs adequately boils down to a partisan divide.”

Among those who think the new philosophy can work is Stacy Deck, an associate professor of social work at Spalding University in Louisville. But she also remains uncertain about whether a single approach is a cure-all for the homeless. Families become homeless for a variety of reasons. Tailoring help on a case-by-case basis could provide better success.

Having appropriate government funding is key.

“Our federal budget is a document that portrays our values as a nation,” said Deck. “If we’re saying we don’t have enough money to help kids who are homeless, what does that say about us?”

A new approach

Let’s talk about Housing First.

At this point, you may be thinking: What an awful program this must be if it’s taking funding away from such vulnerable populations.

Here’s the kicker. Housing First has actually been proven to work in certain instances.

Deck helped to break down this complicated issue.

Housing First addresses the fundamental requirement of shelter by offering permanent housing. We’re talking Maslow’s hierarchy-of-needs stuff here (air, water, food and shelter). Get people into housing immediately, and a big obstacle in their lives will be removed, the thinking goes.

Supportive services, such as addiction treatment and mental health counseling, may then be sought from other agencies, if needed. In fact, Deck said, interventions when forced on individuals are generally less successful. With flexibility, clients can be steered toward assistance that best suits them. Caseworkers might be assigned, but, in general, HUD funding wouldn’t be used for these services.

“What’s important to remember is Housing First does not mean housing only,” Deck said. “It means housing right away, with supportive services attached. There’s a respect for the individual’s self-determination. They select which services they are ready for.”

Several studies have backed up this line of thinking, including one undertaken by HUD called the Family Options Study. Between September 2010 and January 2012, 2,282, families from emergency shelters across 12 cities were randomly assigned to one of four interventions:

permanent housing subsidy only, with no supportive services attached

project-based transitional housing

community-based rapid rehousing

usual care (such as remaining in the shelter).

For three years, the families were monitored and data was collected. Eighteen months in, HUD released preliminary findings. While the least costly, the permanent housing subsidy almost counter-intuitively proved to be the most effective at stabilizing families and improving their overall wellbeing.

In fact, Housing First has helped Louisville’s Coalition for the Homeless to reduce the number of individuals living on the streets. A 23-percent drop in the homeless population over the past four years can be seen as a testament to both this philosophy and other collaborative projects.

Just last year, the Rx: Housing Veterans initiative allowed the city to reach functional zero for veteran homelessness. In other words, the number of veterans without a home remains less than the monthly housing placement rate for this population. Yes, veterans who are homeless may still exist, but the resources are available to get them immediate help. The next major goal for the coalition to eliminate is to end chronic homelessness.

But Deck cautioned that experimental designs don’t always resemble real life. Not all families who are homeless have access to the vouchers and priority placement given to those in the Family Options Study, making the adoption of the Housing First philosophy complicated. There’s just not enough affordable housing, and the federal programs that do exist can’t meet the needs of the community. Adding to this, discrimination, zoning regulations and classism prevent workable programs from being instituted in the first place.

“We’re nowhere near providing housing assistance to everyone who is income-eligible for it,” Deck said. “We’ve got legal problems. We’ve got funding problems. We’ve got discrimination. It’s a perfect storm.”

Among the doubters are people who need the help — like Thornton, who lives at the 12-bed home in downtown Louisville that serves men and women with HIV and AIDS who have no place to call home.

He said he doesn’t believe Housing First tackles the underlying problems, like addiction or health issues, that may cause homelessness.

“If you take someone straight off of sleeping on the sidewalk and say, ‘OK here’s your home’, but they haven’t been able to develop the skills to maintain that home like they can through a transitional, they’re just going to be doing the same thing but they’ll be doing it in a home,” the former warehouse worker said.

The Aftermath

Thornton has nowhere else to go.

He sits in a room adorned with words and tells his story of how he came to Glade House, the longest-running, continuously-operating shelter of its kind in America.

In 2008, Thornton first arrived at this home and stayed for nine months. His alcoholism brought him back two months ago, after he lost everything again.

“Without this place, I’d still be in my car,” he said. “To me, this is the only place in town.”

Glade House gave him sanctuary and hope.

Not only did he have a place to stay with 24-hour, around-the-clock staff, the nonprofit also helps him manage his health and get his life back. Outpatient addiction treatment, individual and group counseling and healthy living courses are just a few offered.

Self-sufficiency remains the ultimate goal. For up to two years, the men and women can stay as their lives stabilize once again. And they do this in a safe, accepting environment where they don’t have to worry about bias and negative reactions to their HIV status.

“This transitions us not just into a home, but into a mental state where we can accept the fact that we’re HIV-positive, and that we’re not victims, but survivors,” Thornton said.

Bracing for cuts

Starting on Aug. 31, the federal money that accounts for 70 percent of Glade House’s budget will be gone.

Yet with the rise of heroin addiction, and the subsequent increase in HIV infection in nearby towns including Austin, Indiana, now more than ever House of Ruth’s services are needed in Louisville.

“Where we’re left is trying to figure out how to fund a type of housing we believe our clients need regardless of what HUD’s policy is,” said House of Ruth Executive Director Lisa Sutton.

Currently, all beds are full, according to Deloris Johnson, House of Ruth’s Director of Clinical Services. In the three months she’s worked here, she’s had numerous people knock on the door looking for an open bed.

“I wish I could just sleep them on the couch,” Johnson said.

Changes will have to be made, including a reduction in beds. Residents have been asked to contribute a third of their paychecks. But that alone won’t come close to covering the impending deficit.

Failure, though, is not an option.

“We’re going to make a way,” Johnson said. “We have to.”

The face of a statistic

The smell of fresh coffee permeates the kitchen of St. Elizabeth Catholic Charities’ Transition Home in New Albany.

Sandy Spaulding sips from her mug as she talks about how she came into the program last October. Her options then were few. Drug addition had caused her to lose her children.

Then, after spending six months in jail, the 32-year-old couldn’t find a place to stay. For two months she remained homeless, until someone suggested she contact St. Elizabeth’s. Through its support, she continues to be drug-free, and recently even regained custody of her 2-year-old.

“If it wasn’t for them, I wouldn’t have got my son back,” Spaulding said. “Now I know what I’m capable of, and I just want to keep doing more and more.”

Like House of Ruth, the seven-bed transitional housing home at St. Elizabeth lost $105,000 of HUD funding this grant cycle, about a quarter of its yearly budget.

While attempting to make the shortfall, Leslea Townsend Cronin, St. Elizabeth’s social services director and chair of the Homeless Coalition of Southern Indiana, questioned HUD’s reliance on the results of their Family Options Study on its shift in policy.

“We’re not Houston. We’re Southern Indiana. Our population is different. Our community is different. Our resources are different. Everything is different,” she said. “So how can they make these grand statements about the United States in general as a whole?”

The lack of communication between HUD and organizations affected by the cuts frustrated Townsend Cronin. Telephone calls have gone unanswered by both her Continuum of Care and HUD representatives. While HUD hopes to eventually discuss how to make their grant requests more competitive, organizing even this outreach could take months.

Most don’t have that long until the effects of the cuts kick in.

“It is going to have to be the community along with the Homeless Coalition and everybody else that steps up,” Townsend Cronin said. “We’re not going to let this federal study of HUD say what our homeless families need. And that’s what they are. They are ours. We need to put our arms around them and help them.” •