Recently we saw the unveiling of U.S. Sen. Mitch McConnell’s Senate version of the Republicans’ plan to “repeal-and-replace Obamacare.” Some commentators were stunned by its audacity in shifting hundreds of billions of dollars from the nation’s poorest citizens, only to give it to people making over $200,000 a year. The Congressional Budget Office has estimated that 22 million people would lose health insurance coverage under McConnell’s bill, about the same as under the House version. The American Public Health Association warned that “the bill would devastate the Medicaid program, our nation’s health care safety net on which 69 million low-income Americans and people with disabilities — including 37 million children — rely.”

Indeed, the announcement was greeted by the sight of disabled protesters being roughly carried from McConnell’s office by Capitol Police.

But how could the Senate Republicans do this? Don’t they even care about the middle-class and elderly people who voted for them in 2016?

Given their own flirtations with Wall Street, the attack on the GOP as the party of the rich by Democrats has always seemed more like muscle memory than a live argument. But, as a matter of history, the accusation that the GOP serves the richest Americans and the large corporations has long been a fair charge, even though at times the party has harbored civil rights and progressive wings (and now Trump nationalists, libertarians and evangelicals).

Born as a righteous opponent of the slavocracy, during the Civil War and Reconstruction the Republican Party was a Northern party and took on that section’s concerns about industry, commerce and economic policy. Wall Street, the railroads, the energy trusts and the rising corporations of the Industrial Revolution of the late 19th century began to dominate its policy and, after the ratification of the civil rights amendments, the GOP’s interest in African-Americans waned (even as Southern Democrats negated those rights with segregation enforced by lynch law).

As early as the Grant Administration, political dominance in Congress began to corrupt the party and minor scandals such as Teapot Dome (a sordid grab for public oil resources) dot its history.

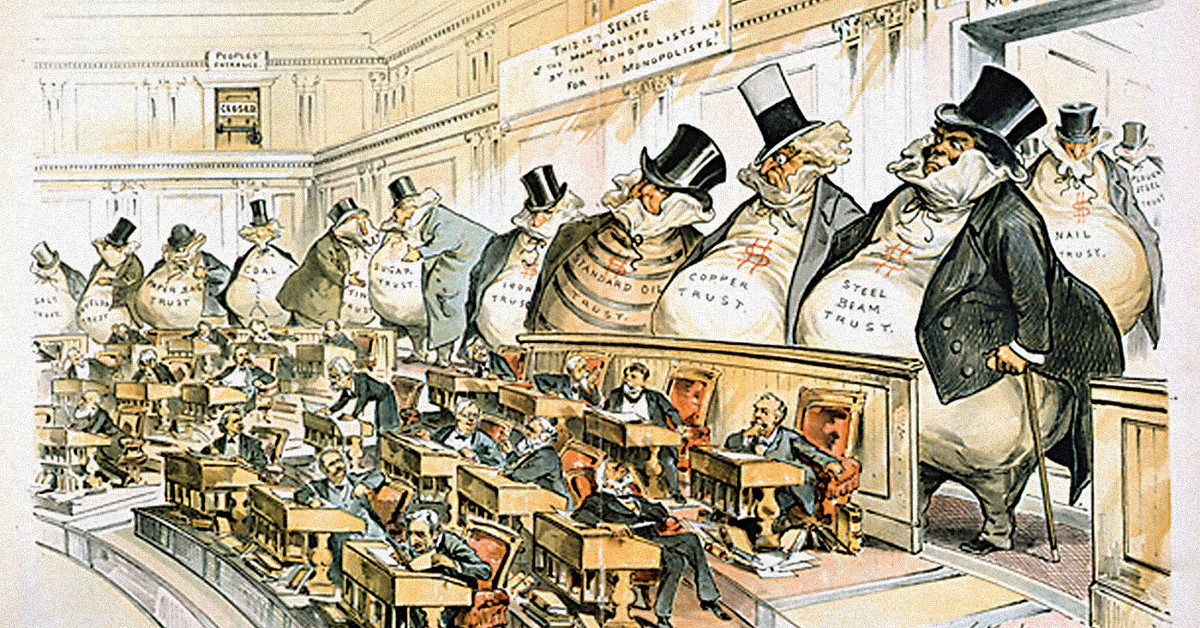

More significantly, by the end of the century, billionaire financiers including J.P. Morgan and Jay Gould were pulling the strings of the party in Congress, a notion embodied in Joseph Keppler’s 1889 cartoon “The Bosses of the Senate,” depicting engorged plutocrats ringing the Senate gallery, watching over their minions. Income inequality was staggering in this era.

Historian Steve Fraser estimates that such wealthy tycoons as Morgan were part of a tiny 2 percent that owned a third of America’s wealth, while almost half the nation shared a miserable 1 percent. The U.S. had not seen inequality like that in its history and would not see it again — although McConnell and his friends are trying.

After brief accommodation with Wall Street interests by President Grover Cleveland (the Bill Clinton of the Gilded Age), some Democrats began to regularly attack the plutocratic drift of the GOP. William Jennings Bryan herded third-party, agrarian populism into the Democratic tent by promoting looser monetary policy and accusing Republicans of “crucifying” farmers and workers on a “cross of gold.” Later in 1906, he argued that:

“Plutocracy is abhorrent to a republic; it is more despotic than monarchy, more heartless than aristocracy, more selfish than bureaucracy. It preys upon the nation in time of peace and conspires against it in the hour of its calamity. Conscienceless, compassionless and devoid of wisdom, it enervates its votaries while it impoverishes its victims. It is already sapping the strength of the nation, vulgarizing social life and making a mockery of morals. The time is ripe for the overthrow of this giant wrong.”

When Franklin D. Roosevelt championed progressive policies to lift the U.S. out of a Great Depression partially created by Republican policies, he was denounced as a class-traitor by his wealthy peers, who spit their hatred at him with an intensity not seen again until the election of Barack Obama. “Never before in all our history have these forces been so united against one candidate as they stand today. They are unanimous in their hate for me — and I welcome their hatred,” he thundered. The plutocrats, FDR said, “consider the Government of the United States as a mere appendage to their own affairs.” We “know now that Government by organized money is just as dangerous as Government by organized mob.”

Donald Trump’s trade and international policies may have upset people comfortable with the Republican Party’s free-trade and internationalist orientation since World War II, but they are paralleled in history. In the early industrial era when the rising corporate class wanted the protection of their goods against more established foreign producers, the Republicans supported high “protective” tariffs and isolationism. In the post-war era, when the corporate class wanted to build up overseas markets, the GOP embraced free trade and an internationalist foreign policy. And while Trump and his congressional party are divided on many things, tax cuts for the wealthy are the one thing that unites them. Indeed, even the prospect of tax relief for the rich has sparked a stock market boom.

And regarding healthcare for the poor, the struggling middle-class and the elderly? History suggests that it is a not high priority for the Adelsons, DeVos and Kochs in the Senate gallery, still pulling the strings of their party, still skillfully operating their marionettes more than a century later. •

Metzmeier is the associate law librarian at the UofL Brandeis School of Law. He is the author of “Writing the Legal Record: Law Reporters in Nineteenth-Century Kentucky” (University Press of Kentucky, 2016).