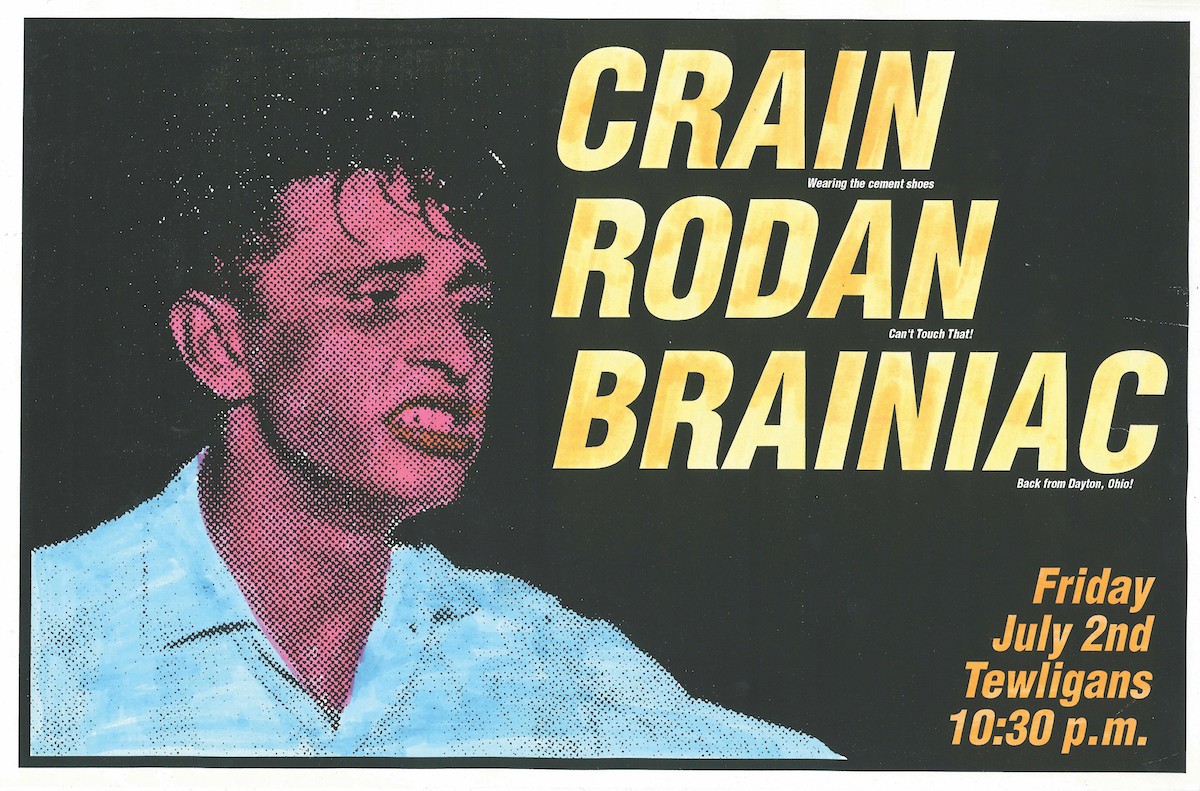

Flyers were what drew Billy Hardison to his first punk shows in the ‘80s, an East End kid taken in by handmade posters with letters cut from magazines, ransom note style. Then, in 1991, when he became the booking agent for Tewligans on Bardstown Road, where Nirvana is now, flyers were how he would attract crowds to his events: At 2 or 3 a.m., after a show, he would go to Kinko’s, now the site of Seviche, and work on a concept with his fellow booker David Gruneisen and graphic designer Tim Furnish. Then, he and Gruneisen would throw a stack into backpacks and race around town on mountain bikes, ripping off old flyers and replacing them with new ones with a few wacks of a staple hammer.

“It was always fun,” said Hardison, who now co-owns Headliners Music Hall, “There was no traffic at 3, 4 in the morning.”

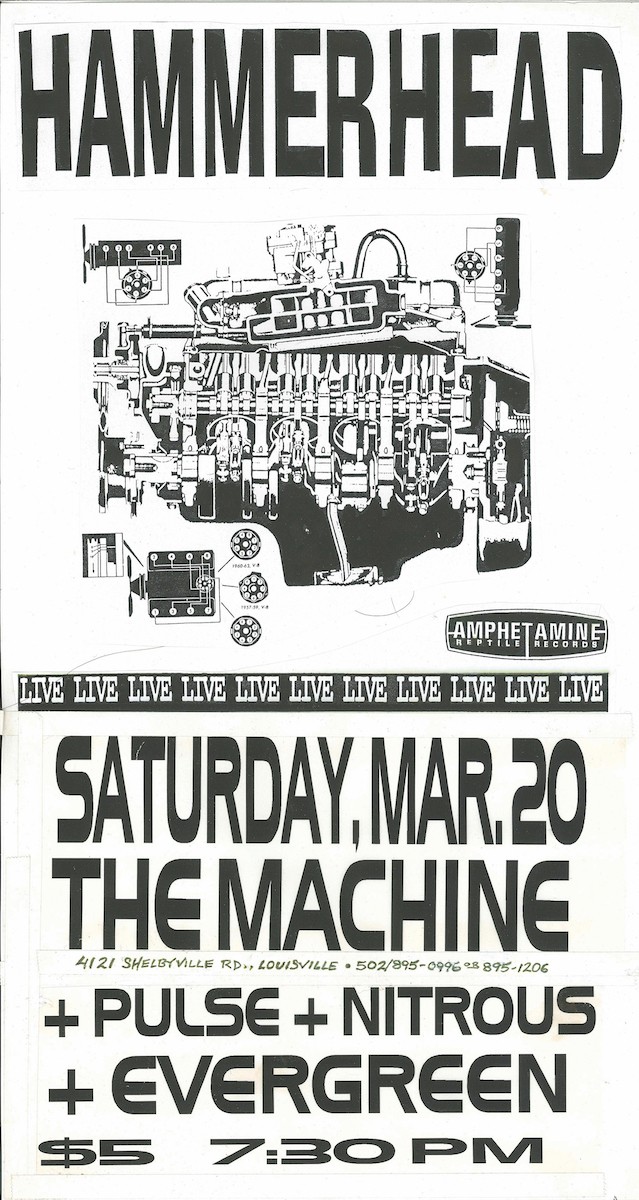

For Hardison at the time, the flyers were a cheap form of advertising underground bands. To many, the flyers that promoted Louisville punk shows in the ‘80s and ‘90s, are works of high street art. But, sometime in the early- to mid-‘90s, they mostly disappeared from Louisville’s telephone poles.

Sometime after Hardison left his job at Tewligans in 1993, the city of Louisville started enforcing an ordinance that doesn’t allow for flyers on poles. Promoters and bands were still able to post flyers in accommodating local businesses, but a small yet precious part of the local music scene had vanished. Stephen Driesler, a co-editor of the book “White Glove Test” that compiled 700 of these flyers, said it was more exciting to see one on a telephone pole than, say, while browsing records at ear X-tacy.

“You’d see a flyer, it wasn’t legible, but it would catch your eye from across the street, and you’d have to run across, like, oncoming traffic to get over there to even see what it said, you know, if it was something really exciting,” he said. “[You’d] maybe tear the flyer down, so you could have the information or just, like, make a note of it… just the randomness, you know, of the unexpected encounter on the street, I think definitely made it more appealing.”

And, when flyers left the streets, so did a slice of local art and history, in Driesler’s opinion.

“You go to a place like Cleveland or Portland, Oregon or something, you know, and telephone poles are absolutely coated in flyers, and they become so dense there it’s like an archeological dig,” he said. “It’s like 100 different flyers stapled on top of each other, and the pole doesn’t even feel like wood anymore. It just feels like it’s made out of paper, and they’ve just kind of fused together from all the years of rain and snow and whatnot. And the poles become these fantastic art objects in and of themselves, and, you know, I think anybody that looks at that and sees that only as litter and ugliness ought to think a little bit more about, like, the possibilities of what can be considered beautiful.”

“White Glove Test” features flyers from 1978 all the way through 1994. The earliest flyers of Louisville’s punk scene were made with collage techniques and stencils and spray paint, Driesler said. Within them, you could catch glimpses of fine art traditions — echoes of Robert Rauschenberg’s pop art and Russian Constructivism. In the ‘90s, when artists started using computers to make the flyers, the designs became bolder, to the point where they could be read from across the street.

Hardison’s main goal when creating a flyer was to make it legible for the largest amount of people possible.

“In some ways, we destroyed the art of it, but we elevated the marketing of it,” he said.

His flyers consisted of black ink on 11-inch by 17 -inch Astrobrights paper, legible even from a car speeding 35 miles per hour down the road.

Hardison also thinks he had a hand in the city deciding to enforce its flyer ordinance — but because of his absence rather than his presence.

When Hardison and Gruneisen embarked on their late night flyer missions, they played what they called “judge, jury and executioner,” with flyers that were already there, taking them down if the duo thought there were too many promoting one event, or if the flyer covered another that was advertising a different show.

In 1993, Hardison and Grunieson left Tewligans because they had a falling out with the owners. Hardison took a step back from the scene: He was still booking shows, but mostly, he was busy working a new job at a bank. It was during that time, when he and Grunieson weren’t policing the use of flyers, that they seemed to proliferate across Louisville.

There was another factor at play, too, said Hardison. When he was at Tewligans, it was one of the few venues in The Highlands that booked bands that played originals. Businesses like Toy Tiger and Phoenix Hill Tavern were more inclined to host cover bands. That is, until grunge music broke into the mainstream, playing on MTV and “alternative” commercial radio stations. These “meat market venues,” as Hardison called them, started booking original talent, leading to more flyers and plastered poles.

Tom Owen, a retired Louisville city council member who represented the Bardstown Road area at the time, said that there were several times over the course of his career when groups across the city decided to crack down on flyers. The impetus was litter — concerns about paper ending up in the street — but also because some flyers carried images that Owen remembered depicting “sexist” and “abusive” scenes. He could clearly recall one flyer that depicted railroad spikes piercing a woman’s tongue. The concern was one shared by him, neighborhood associations and LG&E, the owner of the poles.

“They were offensive,” he said about the flyers. “Not all of them, but some of them were offensive. So if you’re going to go after some, better go after all.”

Driesler agreed that some, but not most, flyers promoting shows used offensive language and provocative images. But, he said there are hazards in elected officials deciding what images and language should be permitted in public.

Hardison said he doesn’t think that the flyer takedown had a long-term impact on the business side of Louisville’s music scene — maybe just three-months worth of course correction. When Hardison started promoting shows, flyers were one of the most accessible ways to do so. It was too expensive to buy ads in the Courier Journal, and the bands at his shows didn’t get radio play, so there wasn’t a point in promoting them there. Their other options were to call the Courier to get a free listing in its event calendar or to get coverage in a small magazine.

But, by the time flyers disappeared from telephone poles, new opportunities for advertising were starting to open up. Radio became more accessible with the growing popularity of grunge, and the internet had started its journey to what it is now: probably the most effective way for bands to promote their shows. LEO Weekly’s emergence played a part, too, said Hardison: It was cheaper to buy advertising here than in the Courier.

In today’s music world, bands can advertise their shows for free on their social media pages. And some even create flyers — artistic ones — that they post, as well. But, at least prior to the pandemic, flyers were still an important part of Hardison’s promotional strategy for his businesses’ shows, because the more times someone sees an advertisement, the better, he said. Now that events are reemerging, Hardison is still trying to figure out whether flyers will be a part of his business plan in the near future.

Driesler said he would encourage people promoting shows today to make their own physical flyers: it’s fun, he said, you’ll probably get a positive response and perhaps most importantly, you can keep it as a keepsake afterward to remember the moment.

“The show is amazing when it’s happening, but our memories are fleeting,” he said. “As time goes by, it’s harder and harder to put yourself back in that night, back at that show, I think. But sometimes, I mean, obviously, there are recordings of shows and there are photos that people take at shows, and sometimes, those can be very evocative. But for me, an object like the flyer really is a way to sort of reconnect with what it felt like to be that age, and to be there, that afternoon, at that all-ages show or that night at that bar and see that band and whether it was super exciting or super boring. But, like, it’s all worth remembering.”