I’ve been writing about capital punishment for about 20 years now, which is about 20 years too long. It’s easy enough to poke holes in the ideas that drive the practice itself; it’s expensive, it doesn’t deter crime, it hits the poor and people of color harder, the rest of the world abandoned the practice long ago, etc.

Likewise, when you’re writing about a death row exoneree who was actually innocent but was sentenced to die anyway, that’s an easy sell. Most people understand that it’s wrong to kill someone for a crime they didn’t commit (though some judges are on the fence about this; Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia wrote in 2009, “This Court has never held that the Constitution forbids the execution of a convicted defendant who has had a full and fair trial but is later able to convince a habeas court that he is ‘actually’ innocent.” That passage can be translated to: “It’s OK to kill innocent people, so long as the process looks fair.”).

Then, there are the real murder cases with the really guilty people and really horrific circumstances. When you examine those cases, high-minded policy arguments tend to dissolve, sympathy wanes and the reader is left thinking, “Well, maybe the death penalty isn’t so bad after all.” This, I suppose, is what keeps a few alt-weekly-reading liberals on the fence about the continued viability of American capital punishment.

Take, for example, the execution of white supremacist scumbag Daniel Lewis Lee in Terre Haute last month. Lee was convicted of murdering two parents and their 8-year-old daughter during a home invasion. He and an accomplice tied plastic bags around their victims’ heads and watched them suffocate to death. Then, they pitched the bodies into an Arkansas river.

Getting people to oppose his death sentence — now there’s a challenge. Since I’m annoyed about capital punishment still making headlines and even more annoyed by the federal government using my home state to stage its gratuitous PR stunts, that’s the ball and chain I’ve elected to affix to my wrist for this week’s column.

First, there’s the simple question of: Why? Why kill this guy instead of keeping him locked up? The family of Lee’s victims, like most victims’ families, didn’t want it. The mother of the woman killed wrote to President Trump asking for last-minute clemency. She even filed suit to stop Lee’s execution. Not only did she think it would tarnish her daughter’s memory, but at age 80, she couldn’t make the trek from Arkansas to Indiana and sit in a cramped viewing room without risking exposure to you-know-what. An Indiana judge pushed pause but was undone by a higher court in an emergency ruling. Lee’s case, which had languished in appeals for nearly 25 years, simply could not wait through a global pandemic, victims be damned. What the hell for? What good did it do?

Then, another district court put the execution on hold because of U.S. Attorney General Barr’s new-and-improved lethal injection protocol, which might result in not only death but prolonged torture. Again, an appellate court promptly shredded that opinion, because the forced shuffling-off of this particular mortal coil was an urgent need. Maybe you don’t much care about how a child killer dies. America’s a violent place, and if one experiences a little extra pain on the way out, them’s the breaks.

Still, you might pity Daniel Lee’s circumstances before his demise, if just a bit. He was 17 when he aided in his first murder and 23 when he helped kill that family in Arkansas. He grew up like nearly all murderers: poor, abused, with traumas that never would have been diagnosed had he not been under the microscope of a capital defense team (because after all, even if you could afford to diagnose your kid’s neurological disorders, you have to care enough about that kid to go do it, and Lee’s parents didn’t). Even one of the doctors who testified against him later recanted, citing new medical evidence about Lee’s undiagnosed, untreated seizure disorder.

Tough luck, right? Everybody had a terrible childhood. But what about the way the system reacts to killers who want to explain those circumstances to a jury? Lee could have gotten life without parole if he had pleaded guilty. Accused murderers who are brave, stupid or mentally ill enough to insist on going to trial are almost always the ones who get death. Lawyers call this the “trial penalty.”

That brings us back to actual innocence. The trial penalty means that the wrongfully accused — defendants who want to go to trial instead of plea bargaining — are more likely to be executed than the guilty. Combine that with the fact that the only people allowed to serve on capital cases are people who support the death penalty (no overdeveloped moral compasses or devout Catholics allowed), and you get a system that has real potential for all kinds of massive fuck-ups. Lee insisted on trial and maintained his innocence until he was strapped to a table and pumped full of pentobarbital. His last words were, “You’re killing an innocent man.”

Was he really innocent? Probably not. Even so, why did this particular guy get the ax? Over 1,000 children are murdered in the U.S. every year, but only a small handful of the murderers are chosen to die. This was the first federal execution since the Oklahoma City bombing, an operation which made Lee’s aggravated murder charge look like a game of “Clue” that got out of hand. Even in the context of this particular case, it doesn’t make sense. Lee’s accomplice, a man prosecutors described as the mastermind of the murders, was another white supremacist who had robbed the same family once before. But he dressed in a nice suit in court, and, unlike Lee, he didn’t have SS tattoos on his neck or a missing eye. The same jury that sentenced Lee to death gave the “mastermind” life in prison.

The system threw a dart, and it landed on Lee. I don’t want a justice system that throws darts and neither do you. And because capital punishment can’t be revoked, it won’t matter if we find out later that Lee was telling the truth. Some might say that no one is beyond redemption. A nice thought, but that’s not what I’m arguing here. I’m saying that neither the federal government, nor a panel of “death-eligible” jurors, should decide who is redeemable.

Even if I’ve convinced you that Lee shouldn’t have been executed, you may be inclined to think that this case is exceptionally nuanced. But I promise you: There isn’t a murder case without nuance. There are always questions of innocence. There are always questions of procedural fairness. There are always mitigating factors that should make any decent person stop and say “wait, do we really need to do this?” or at least “should we give the government the power of life and death over regular slobs, even the ones we don’t like?” The rest of the world has figured out the answer to those questions. Maybe someday we will, too.

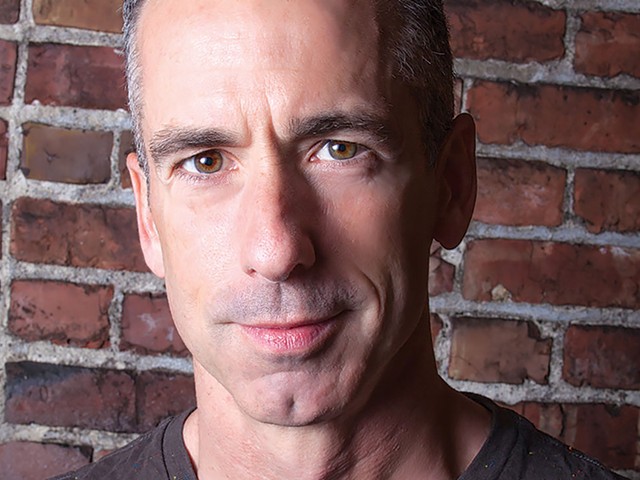

Dan Canon is a civil rights lawyer and law professor. “Midwesticism”is his short-documentary series about Midwesterners who are making the world a better place. Watch it at: patreon.com/dancanon.