This article is a part of the 2019 Bourbon Issue. For more, click here.

Kentucky now welcomes about 1.5 million visitors each year who come specifically to see where and how bourbon is made (and maybe to drink some). Most distillery and museum tours mention how early Ohio Valley settlers brought their stills with them to make whiskey on their farms.

Not one of the tours, however, shows a working demonstration of that important early chapter in Kentucky’s bourbon history.

That is, until now.

Historic Locust Grove, the last home to Louisville founder George Rogers Clark, has had a farm distillery since May 2017.

It is not licensed yet, so no alcohol is being produced, but you can watch the cooking of mash, either from grain or fruits, some harvested from the property. Some of the mash has been taken to Kentucky Artisan Distillery in Crestwood where small amounts have been fermented and distilled. Eventually, this could be bottled in small quantities and sold to benefit Locust Grove. But, that’s in the future.

To get to even this point took much work and a lot of deep connections to Kentucky’s bourbon royalty. The list of donors and organizers includes Kentucky’s old bourbon distilling families and artisans.

Here is how Locust Grove board member Sally Van Winkle Campbell (yes, that Van Winkle) recounts how the project came together so fast. Locust Grove Executive Director Carol Ely mentioned to her that creating a distillery on the farm had been talked about.

“But nothing was actually planned,” Van Winkle recalled her saying. “I felt that maybe I could do something because I didn’t really have a job as a new board member.”

Campbell could “do something” thanks to her connections in the bourbon community. Her grandfather was the legendary Julian “Pappy” Van Winkle, and her brother, Julian Van Winkle III, helms the Old Rip Van Winkle and Pappy Van Winkle whiskeys. Campbell asked Van Winkle to donate some bottles of his sought-after brands to help raise money to build the distillery. A national online auction of the bourbons in November 2017 brought in $20,000. She also called on other families associated with heritage bourbon brands to help with funding.

“The Browns and the Samuels and the McClures — everyone wanted to help. And, so it just kind of took off,” she said, adding that master still maker Vendome Copper & Brass Works made a replica of the kind of still that would have been used.

Campbell’s neighbor Dominic Pagano, a bourbon enthusiast and engineer, pitched in to help with structural details, including drawing plans, laying bricks and even crafting the wooden water races. She credits him with “a passion for history, a big heart and boundless energy.”

Of course, once the distillery was built, there needed to be someone to operate it. That responsibility fell to Brian Cushing, Locust Grove’s program director. Cushing had never visited one of Kentucky’s major distilleries, but he immersed himself in the process. He went to the Wilderness Trail Distillery in Danville, Kentucky to become familiar with the distilling equipment and process. He also spent time at Mount Vernon, the Virginia estate where George Washington’s commercial distillery has been recreated and annually produces a limited bottling of rye whiskey. Its stills were made by Vendome as well, and Locust Grove’s much smaller still is modeled on one made for Mount Vernon.

There is certainly evidence that Locust Grove’s first owner, Major William Croghan, would have been a distiller, too, but on a much smaller scale. “The estate was originally almost 700 acres. (The current property is 55 acres.) We know Croghan had a mill, and we have a record that he purchased a 66-gallon still in 1808,”said Cushing.

A little detective work by bourbon archaeologist Nick Laracuente brought to light the probable location of the mill. He scouted along the stream in neighboring Riverwood subdivision that would have been part of the original Croghan estate and spotted “a place that was very likely for the mill’s location.” He emphasized that “very often” across the state, farm-scale distilleries were associated with mills.

Unlike Washington, Croghan was not distilling for wide distribution, but rather for crop processing and crop preservation, Cushing said. “The bottom line was you could either let your excess grain and fruit spoil and lose its financial return, or you could distill it onto something portable and preserved.”

In short, make whiskey and brandy.

Ironically, this was probably not what the Croghan family itself was drinking. “We’ve got account records of William Croghan purchasing mainly rum and Madeira, which seems to have been his preferred beverages.”

Because the probable site of the original mill and distillery is no longer on Locust Grove’s property, the recreated distillery is situated in a log cabin found just outside the northeast corner of the garden quads, a short downhill walk from the three-story, red-brick Georgian house. During a recent afternoon tour, Cushing, dressed in period costume, was adding logs to the fires that heated a copper boiling tub.

He was also feeding the fire beneath the small, brick-encased, copper pot still, as he explained how the distillery would have fit into early 19th century farm life. Holding up a stoneware jug, Cushing recounted that the distillate produced would probably never have seen the inside of a barrel. It was not what we now know as bourbon. “What was produced was what we would call ‘white dog’ or ‘new make,’” he said. In other words, very likely a corn whiskey that was a bourbon “ancestor.”

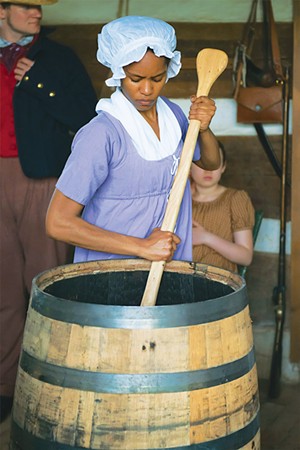

During demonstrations, visitors can get an up-close look at a process that was an important part of early 19th century farming. They may even get a chance to stir the mash with a special paddle. And they also hear that the people who did the real work of distilling were not paid distillers, but the enslaved African American people on the property, an aspect of Locust Grove’s history that its tour docents do not shy away from acknowledging and spend time talking about.

By prearrangement, the group that Cushing was guiding through the distilling process met at the end of its tour in the Visitors Center for a tasting of commercially distilled new make whiskey and brandy, the sort of spirits that would have come off of the Locust Grove still. All were a bit rough to most samplers, so as a “palate cleanser” the final product sampled was a taste of Woodford Reserve.

Isabel Clark, a visitor from New Orleans, was impressed with her entire experience at Locust Grove, but as a bourbon enthusiast, she was very taken with the distilling story. “That small open-air building brought the origins of bourbon close to home. In that one room you [get] the true essence of what it meant to bring whiskey to the table in the early 1800s.” •

How to go

For more information about Locust Grove, its distillery and programs, visitlocustgrove.org or call 897-9845 for a schedule of tours and demonstrations.