During the 2012 election, California became the battleground in a national proxy war over genetically engineered food. A ballot initiative facing the state’s 12 million voters was Proposition 37, “A Mandatory Labeling of Genetically Engineered Food Initiative.” If passed, it would have forced food manufacturers selling products in that state to reveal which products contained genetically modified, or GMO, ingredients.

Genetically modified ingredients are present in an estimated 75-80 percent of all processed foods in the United States. According to the Environmental Working Group, America’s per capita consumption of genetically modified foods has reached 193 pounds annually — 14 pounds more than the average citizen’s body weight — in the form of beet sugar, corn syrup, soybean oil and corn-based products. The only way consumers can currently avoid GMO-based food is by purchasing certified organically grown or Non-GMO Project Verified foods — or by growing their own.

With California’s $2 trillion economy and 38 million residents — representing nearly 12 percent of the U.S. population — Prop. 37 could have inflicted a serious chink in the armor of the agro-chemical companies that dominate the growing of commodity crops nationwide. The California market is so large that if food producers had to change labels there, they’d have to do it everywhere. The GMO industry would no longer enjoy its invisible hegemony over supermarket shelves.

But the California labeling initiative soon became just another speed bump on the biotech industry’s march to dominate food and agriculture systems. Even as the industry corralled and spent upwards of $46 million to eke out a 51.7 percent to 48.3 percent marginal victory at the ballot box, they were maneuvering to release a whole new generation of products that are less regulated, less healthy and less understood by the American public.

61 Countries Label GMOs — But Not the U.S.

Labeling genetically modified products is standard practice in 61 countries, including all members of the European Union, India, China, Russia, Australia and Brazil. Back in 2007, presidential candidate Barack Obama promised he would support a national GMO labeling law, “because Americans have a right to know what they’re buying.”

But Obama’s promise was rarely repeated beyond that mention on the campaign trail. That’s because the GMO industry has long enjoyed a nearly sacrosanct relationship with U.S. regulatory agencies. In 1992, at the urging of Vice President Dan Quayle and biotech industry lobbyists, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration awarded GMO foods “generally regarded as safe” (GRAS) status.

Despite the relatively short time these engineered crops had been in existence — and misgivings from its own agency scientists about potential health and environmental risks — the ruling exempted GMOs from mandatory safety tests. Finding no detectable differences between GMO and conventional crops (besides the intended engineered gene), the GRAS ruling merely encourages biotech companies to engage in a voluntary safety consultation with the FDA before releasing a product into the market.

One can only wonder whether consensus was actually achieved among agency scientists when the FDA decision was made. At the time of the 1992 GRAS ruling, there were no studies regarding potential human health impacts from genetically engineered crops. Most environmental and public health studies that did exist had been conducted by the biotech corporations themselves. And much of the data remained sheltered from the public for confidentiality. The commercialization of GMO crops without adequate regulation would essentially turn over control of American commodity agriculture to a handful of chemical companies.

Many critics point to the revolving door between government and industry: An alarming list of top governmental officials have been tied to the biotech industry. They include the head of the FDA at the time of the GRAS decision, Michael Taylor, formerly a partner in a law firm that represented biotech giant Monsanto Co. Four years later, Monsanto’s Roundup Ready soybeans became the first such genetically engineered crop approved for American agriculture. Since 1998, the FDA has rewarded 95 percent of the GMOs introduced by the industry with a free pass on health and safety reviews.

Studies suggest that eating most GMOs isn’t harmful. But without labeling or a sound regulatory system, the public remains unequipped to detect those GMO ingredients that could cause a health hazard. Across the Atlantic, the European Union has embraced the precautionary principle, an approach toward risk assessment of new technologies determined by independently generated scientific data rather than power politics.

State Food Fights on the Rise

California served as a staging ground for a national food fight in 2008 when the Humane Society of the United States squared up against out-of-state agribusinesses around animal welfare. Even though relatively little sow breeding or egg or veal production take place in California, Proposition 2 called for the phase-out of cruel livestock confinement techniques. Nearly two-thirds of the state’s voters supported the reforms. That law has changed the debate about livestock standards around the country.

Out-of-state actors also weighed heavily on both sides of the Right to Know campaign surrounding Prop 37. And it was more than a simple matter of consumer choice.

The Yes on Prop 37 campaign was led by organizations like the Organic Consumers Fund, Food Democracy Now, Just Label It, Food and Water Watch, the Center for Food Safety, and corporate sponsors such as supplement producer Mercola, natural soap maker Dr. Bronner’s, and Lundberg Family Farms.

But the allies of mandatory GMO labeling were fiscally overpowered by the world’s largest biotechnology firms: Monsanto, Dow, DuPont and Syngenta, which poured tens of millions into the fight. The Grocery Manufacturers Association and its members, along with industrial food processors, from PepsiCo and Coca-Cola to Nestlé, General Foods and Sara Lee, piled more millions into the anti-labeling arsenal.

Early polling data showed Californians in favor of labeling by a two-to-one margin. But that was before the No on Prop 37 coalition, with a $46 million war chest, unleashed a tsunami of ads that deluged Californians with a simple message: Prop 37 would cost consumers more money at the checkout counter and pile more regulations atop an already over-regulated food safety system.

What’s a GMO, Anyway?

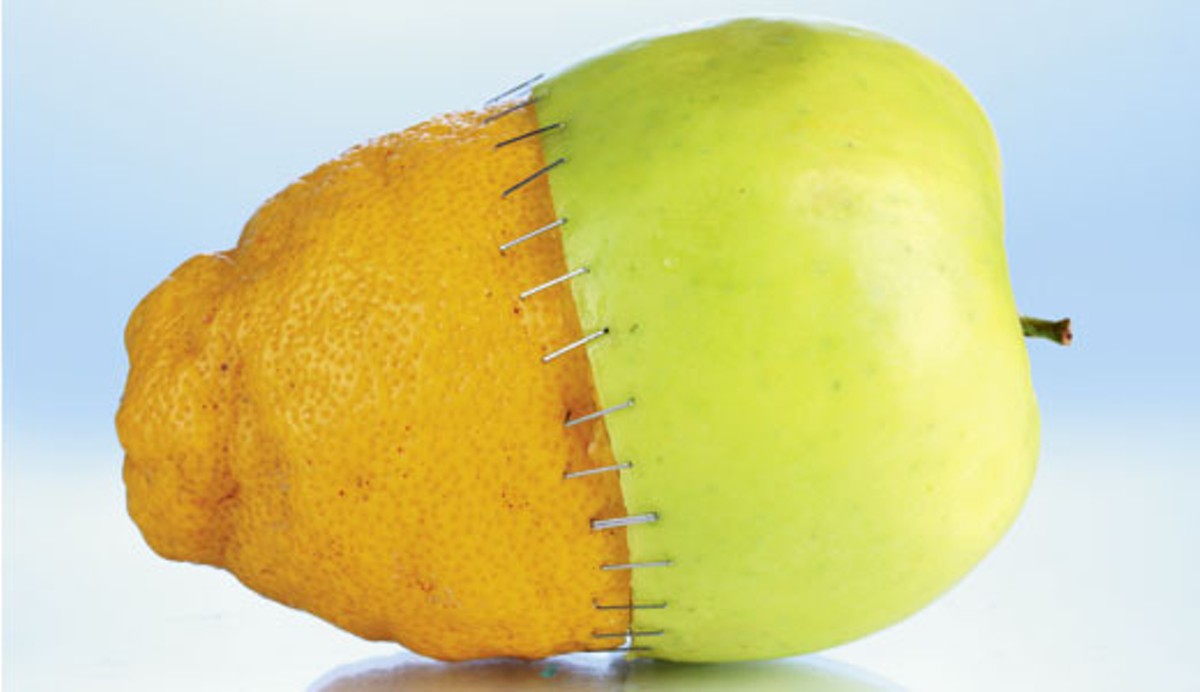

A GMO, or genetically modified organism, is a plant or animal whose DNA has been altered through biotechnology. This is typically accomplished by transferring DNA from one species to another. Often a virus or bacterium is figuratively slammed into a plant tissue culture to create new patentable genetic features in the GMO crop. Plant scientists contend that genetic exchanges outside of species boundaries, such as those between bacteria and viruses and plants and animals, are part of the natural process of evolution. Genetic engineering, they argue, simply mimics interactions in the field.

The inter-species leaps accomplished inside laboratories, however, are completely artificial. They fabricate evolutionary partnerships not possible in conventional plant breeding. Other DNA transfers, such as the insertion of a fish gene into a tomato or human growth genes into pigs and fish, transcend previously impenetrable species boundaries.

Not long before genetically engineered crops were introduced in U.S. farm fields in the mid-1990s, large chemical corporations like St. Louis-based Monsanto, with huge stakes in pesticide manufacturing, began buying up seed companies. The most currently marketed biotech crops have been implanted with a gene that makes them herbicide tolerant. That is, they are resistant to weed killers like Roundup, which incidentally, is sold by Monsanto, the same corporation that applies for the seed patent.

Engineered for Profit

Most GMOs are commodity crops that form the building blocks of the industrial food system: corn, cotton, soybeans and canola. These provide the raw materials for animal feeds, vegetable oils, biofuels and thousands of other manufactured ingredients, like high-fructose corn syrup, that make their way into most of the world’s processed foods. (This may change in 2013, however, as the U.S. Department of Agriculture and FDA consider allowing genetically modified whole foods to market.)

Existing GMO crops haven’t made foods tastier, healthier or longer lasting. They haven’t helped farmers deal with climate change or resource challenges like drought or heat tolerance. Instead, the technology has primarily been harnessed to create a pesticide “package” that services a farmer from seed to harvest. For agro-chemical corporations like Monsanto, Dow and DuPont, profit is harvested along the way

Farmers buy the patented seed from the biotech company. Farmers also buy the herbicide manufactured by the company to which the crop has been made resistant. As an obligation of the licensing agreement, the farmer is not allowed to save seed for next year’s planting. This assures that the profit cycle begins all over again the following year. It also breaks a millennia-old tradition of seed saving practiced by farmers since the dawn of agriculture. And in the conventional commodity crop business, where upwards of 90 percent of all soybeans are now genetically modified, it becomes increasingly difficult and expensive for farmers to find uncontaminated non-GMO seed.

But a technology initially sold to make farming more efficient and less labor intensive has also come at a high price — to the advantage of shareholders of biotech firms. According to the USDA’s Economic Research Service, between 1995 and 2011, the average per-acre cost of soy and corn seed rose 325 percent and 259 percent, respectively. These are the same years in which GMO soy and corn went from less than 20 percent of the total annual crop to more than 80 percent for corn and 90 percent for soy.

“The biotech industry has done a great job of making people believe biotech is all about miracle super crops,” says Bill Freese, science policy analyst with the Center for Food Safety. “We should not let them set the terms of the debate on that fantasy theme… Let’s deal with what they’ve put out there already and what’s in the pipeline, which is overwhelmingly herbicide-resistant crops.”

According to Freese, 85 percent of worldwide GMO crop acreage is comprised of herbicide-resistant plants. And 12 of 16 new GMO foods awaiting USDA approval are herbicide-resistant.

A Tool for Monoculture

Among the biotech industry’s main selling points for new herbicide-resistant seeds was their purported environmental benefit. Roundup was heavily promoted by the industry as “biodegradable” and “good for the environment” despite significant toxicity concerns. Agro-chemicals were already responsible for serious health and environmental problems across rural America. Using Roundup Ready would theoretically reduce the need for older generations of more toxic pesticides.

For conventional corn and soybean farmers, GMO crops seemed like a miracle tool to help them farm more efficiently. Commodity farmers blanket extensive areas with just a single plant, known as monoculture. Weeds are the bane of monoculture farming, as healthy ecosystems naturally tend toward a diversity of plant communities. Removing weeds requires either applications of herbicides, tractor cultivation, manual labor, crop rotations or other careful management techniques — all of which require time and money. The ability to plant a field that could be sprayed with weed killer without harming the crops would make monoculture farming that much easier.

Rise of the Super Weeds

In the early years of GMO farming, crop yields increased and herbicide use declined. Unfortunately for farmers, the golden age of GMOs was short-lived. By 2002, crops like pigweed, ragweed and horseweed developed herbicide tolerance as well. Instead of one annual spraying of Roundup as was done in the early years of GMOs, farmers in many areas of the country had to spray more frequently. When multiple applications no longer sufficed to kill the weeds, farmers went back to using cocktails of multiple chemicals. The longer the resistant weeds were exposed to chemical applications, the stronger the resistant trait was expressed across the landscape.

By 2012, only 16 years after the first GMO crops were released, between 70-80 million acres of croplands had been affected by what scientists now refer to as herbicide-tolerant “super weeds,” according to Penn State University weed scientist David Mortensen. (Mortensen bases this acreage on industry reports. All totaled, it represents an area larger than the entire state of Iowa.)

The industry has responded by pushing ahead with its herbicide-intensive agenda. At least five new GMO crops are now pending USDA approval with resistance to older chemicals. Dow Chemical has applied for corn, cotton and soybeans resistant to the 2,4-D herbicide, a toxic ingredient used in the Vietnam War chemical Agent Orange, which has been linked to cancer, Parkinson’s Disease, nerve damage, hormone disruption and birth defects. Monsanto is also in the USDA regulatory queue with Roundup Ready corn and soy stacked with resistance to the herbicide dicamba, a close relative of 2,4-D.

Even before this reversal toward older, more potent herbicides to deal with the plague of super weeds, herbicide use on U.S. farms was steadily rising. According to a study by Charles Benbrook, a research professor at the Center for Sustaining Agriculture and Natural Resources at Washington State University, genetically engineered crops have led to an increase in overall pesticide use, by 404 million pounds, from the time they were introduced in 1996 through 2011. Introducing a new generation of crops tolerant to a different herbicide is predicted to significantly increase the amount of chemicals sprayed across the fields of rural America. Just as alarming, dicamba and 2,4-D are known to vaporize more easily than most herbicides. They can travel for miles, impacting non-target crops, human communities and wildlife long after application.

“The irony,” says Mortensen, “is that GMO crops were originally marketed as a benign alternative to conventional agriculture. Now we are rapidly moving in the opposite direction.”

Not all farmers are following the biotech industry’s lead. Mortensen is working with Pennsylvania farmers who have returned to farming practices that suppress weeds and sustain healthy soil without the need for an escalation of chemical pesticides and fertilizer applications.

“We desperately need to move in this direction with our incentives to farmers,” says Mortensen. “These practices not only help to manage weed problems, but reduce fertilizer runoff, limit soil loss and capture atmospheric carbon.”

While industrial agriculture forces defended themselves against the labeling issue in California, their herbicide tolerance agenda was also being pushed ahead at the federal level. Added on to the House Agriculture Committee’s draft 2012 Farm Bill was a rider aimed at fast-tracking the USDA approval process for GMO crops. A second rider was adopted that would have weakened the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s powers to regulate pesticides. Neither was included in the nine-month Farm Bill extension passed as part of the fiscal cliff bargain, but they are likely to resurface in future policy negotiations.

Public Health Issues

In September 2012, a French molecular biology professor named Gilles-Eric Séralini published a study in the Journal of Food and Chemical Toxicology that has come to be pivotal in the GMO food fight. After years of litigation to obtain the data relevant to a previous Monsanto food safety study, followed by years of fundraising, Séralini set out to re-analyze the industry-sponsored crop safety research.

The researcher used the same strain of rats and sample sizes that were used in Monsanto’s toxicology study. The rats were fed similar dosages of specific diets, including both non-GMO corn and GMO corn. The Séralini rats were studied over two years (nearly the average life expectancy of the animals), as opposed to nine months in the Monsanto trial. His research team reported that the rats suffered increased liver and kidney damage from extended exposure to GMO corn. Some developed grotesque tumors. Some died earlier than the control subjects.

Pro-GMO scientists immediately attacked the study as biased, partisan, without scientific rigor and fraudulent. The Séralini study was in fact funded by anti-GMO groups in Europe. But in fairness, most of the scientific studies with favorable results on the safety of GMO crops have been funded by industry or pro-biotech institutions. And much of that industry research data has never been made public.

“The study was immediately and forcefully criticized for employing poor methodology for a cancer study,” explains Andrew Kimbrell, executive director at the Center for Food Safety. “This was never intended to be a cancer study. Tumors showed up in the mice, and the researchers reported them. But this was conducted as a toxicology study. And it did report some very alarming findings about the organ damage resulting from consuming GMO crops and Roundup herbicide.”

There are definite limitations to Séralini’s research. Its sample size was small, as is typical of toxicology studies. And of course, one study does not an issue make. Yet many scientists agree the Séralini results should be carefully regarded by government agencies. They call for more independent review, along with further in-depth trials. If anything, the study points to what the public still doesn’t and cannot know. Without a national labeling program, or a wide body of research, how can anyone assess and trace the safety of GMO foods in any ongoing scientific fashion?

The California Showdown

Even in a food-conscious state like California, a large percentage of the voting public has little basic understanding of GMOs. In addition to the need to bring California voters up to speed, the Yes on 37 Campaign was at a severe financial disadvantage.

Meanwhile, the No on 37 team enjoyed an uncontested, month-long media blitz in October as the Yes campaign hustled to raise funds. Slick television ads featured testimonials from physicians and farmers warning voters about rising food prices aired during sporting events, comedy shows and news hours.

In the end, the No on Prop 37 forces outspent their opposition on communications by more than $40 million. Pro-GMO labeling advocates managed to produce a number of effective communication pieces in the last few weeks of the election. But it was too little too late.

“One of the troubling takeaways with Prop 37 is that we were not on an even playing field with contributions from the large food companies,” says Kimbrell, who helped draft the proposition. “The opposition got major funding from industrial ag and chemical companies while many of the major organic players either gave minimal support, no support, or even supported the ‘anti’ campaign.”

Almost as soon as the final votes were tallied in California, advocates of GMO labeling were back in attack mode. A GMO labeling initiative was introduced in the state of Washington, and bills and referenda are pending in Vermont and Connecticut with many other states (though not Kentucky or Indiana) preparing for some kind of action. Prop 37 quickly became a smaller battle in the larger war for better labeling and regulation of GMOs. Missing from this expensive and politicized campaign was a sense of the larger issues at stake.

“The public should be alarmed about the defeat of Prop 37 not only because most people want to know what’s in their food,” says microbiologist Doug Gurian-Sherman, a senior scientist at the Union of Concerned Scientists and author of a well-regarded report on GMOs, “but because the unregulated expansion of GMO crops entrenches a system which, taken as a whole, is bad for public health.”

The 2013 GMO Food Fights

Gary Hirshberg is chairman of yogurt maker Stonyfield Farm and the “Just Label It” campaign, a lobbying organization with more than 550 organizations and businesses that have signed on to its effort to require GMO labeling at the federal level. Hirshberg believes that as a direct result of the attention Prop 37 generated, people at the highest levels of business and government are reconsidering their attitudes toward GMO labeling.

“With future labeling campaigns in as many as 20 states, executives are beginning to look for some other solution. Many fear facing an extended and costly battle on top of the exorbitant cost of Prop 37,” Hirshberg says. “The business community is equally wary of being associated with corporations that don’t believe consumers should have the right to know what’s in their food.”

Around the same time Californians were voting on the Prop 37 labeling law, the cabinet of Kenya banned the importation of genetically modified foods. Their justification: inadequate scientific research on the safety of foods containing GMOs.

The defeat of mandatory food labeling in California is only a temporary setback in the movement to create an open and healthy food system for Americans. Because in a world without labeling, consumers don’t get to peer behind the curtain onto the landscapes where foods are farmed and where human communities and wildlife are poisoned by massive agricultural operations.

But will mandatory GMO labeling be enough to protect public health? In squeaking by in California, the industry bought more time. With that time, they could gain deregulation of a whole new generation of genetically engineered products, like herbicide-tolerant sweet corn, fast-growing salmon, the non-browning apple and commodity crops resistant to more potent classes of chemicals, resulting in the inevitable uprising of even more resilient super weeds.

The issue of GMO labeling not only pertains to making informed decisions about the foods the public consumes, but what it really takes to get that food from field to table, who benefits along the way, and at what cost to society.

Dan Imhoff wrote “Food Fight: The Citizen’s Guide to the Next Food and Farm Bill” and is co-founder of the Wild Farm Alliance. His article first appeared in E/The Environmental Magazine in March 2013.

Free pass for Monsanto?

Last week, President Barack Obama signed House Bill 993, which ensures the federal government will remain funded, at least for the next six months. But buried in the bill was an unrelated provision that food safety activists claim is a free pass for producers of genetically modified foods.

It’s been dubbed the “Monsanto Protection Act” by critics, who claim the bill strips federal courts of the power to restrict genetically engineered plants or seeds, regardless of potential health risks uncovered by future research. Specifically, the bill grants the USDA the authority to override judicial rulings on the matter.

Though GMO critics are sounding the alarm, it’s unclear whether much has really changed. According to NPR, the USDA already has such authority, and a close reading of the bill reveals “it authorizes the USDA to grant ‘temporary’ permission for GMO crops to be planted, even if a judge has ruled that such crops were not properly approved, only while the necessary environmental reviews are completed. That’s an authority that the USDA has, in fact, already exercised in the past.”

Either way, thanks to this bill being the latest in a series of temporary government-funding measures, the legislation expires in six months, meaning the provision — regardless of its ramifications — should be short lived.