State Rep. Attica Scott was the primary sponsor on 14 bills during the Kentucky General Assembly’s 2021 session. They would have, among other things, required Kentucky Medicaid to cover lactation services; banned no-knock warrants throughout Kentucky; and eliminated taxes on feminine hygiene products.

None passed. In fact, no bills primarily sponsored by Scott, D-Louisville, have passed at all since she became the first Black, female legislator to be elected to the statehouse in almost 20 years. And, until this year — since at least 2017 — no bills led by Kentucky’s Black (and all-Democrat) legislators have passed, according to a data analysis by LEO Weekly. In that same time period, starting when Republicans took over both chambers, white Democrats have managed to pass 4.6 bills a year on average — a paltry number, but still more than their Black colleagues.

Even when factoring in bills that Kentucky’s Black lawmakers are co-sponsors on, their endorsed legislation has consistently not passed as often as bills featuring white Democrats. This year, 11 out of 144, or 7.6%, of bills that Black legislators were co- or primary sponsors on passed. But, 45 of 282, or around 16%, of bills with at least one white Democratic sponsor of some sort passed.

Eight of the legislature’s 33 Democrats are part of the Kentucky Black Legislative Caucus, which also includes Rep. Nima Kulkarni, the only Asian American lawmaker in the state house. None of her primarily-sponsored bills have passed either since she joined the legislature in 2019.

This year, freshman lawmaker Rep. Pamela Stevenson, D-Louisville, a retired colonel, pushed through House Bill 398, which she says will help house veterans without homes and feed those without steady access to food by reorganizing the state Department of Veterans’ Affairs.

Scott said she celebrates Stevenson’s win. But — “We also acknowledge that in five years, one member has had a bill pass, and it took five years to get there.”

Opportunities for Kentucky’s Black lawmakers to pass bills evaporated when Republicans claimed their supermajority.

“Institutional and systemic racism is real,” said Scott, “and once the Republicans became the majority in the legislature, that’s when we effectively had bills by members of the legislative Black Caucus either not heard or not passed.”

It’s been difficult for white Democrats, as well, but Scott said she has watched while at least some of her party colleagues have had their bills receive hearings, pass and be signed into law.

“We have had none of that as members of the legislative Black Caucus,” she said.

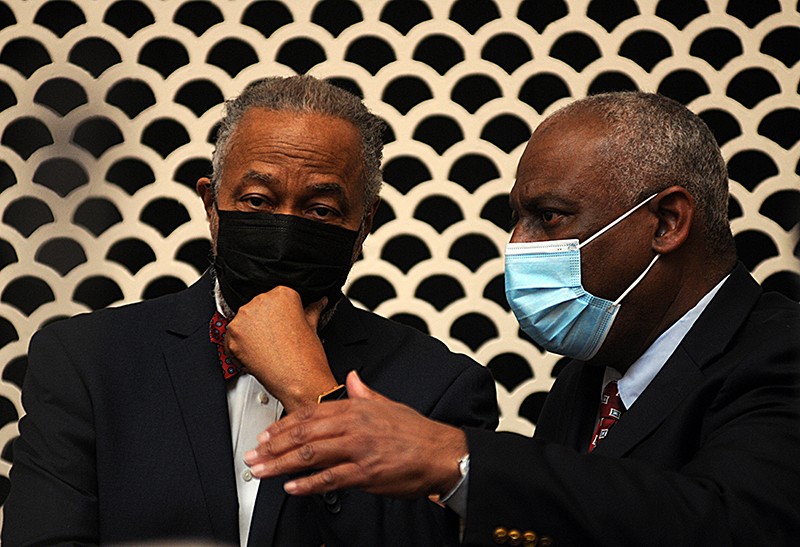

Senate President Robert Stivers, R-Manchester, said that he thinks the reason why Black legislators don’t get bills passed has more to do with a difference in party and philosophy than anything else, and there is still an opportunity for members of the Black Caucus to have their perspective heard, even in the minority.

“The opportunity to voice your perspective and have a chance to add your perspective is in the committee and on the floor,” Stivers said. “And that stays the same and has been consistent for my whole career whether Republicans or Democrats controlled the chambers.”

David Osborne, R-Prospect, the speaker of the House, said in a statement that his chamber is “committed to crafting good policy, not necessarily” Republican or Democrat policy.

“Since being given the majority in 2016, our primary focus has been improving the quality of life for all Kentuckians by creating jobs and growing our economy, increasing access to health care, and investing in education,” he said. “The majority of bills we pass receive bipartisan support and a fair amount of the legislation is the result of collaboration and bipartisan cosponsorship.”

Sen. Gerald Neal, D-Louisville, the longest-serving member of the Black Caucus said there’s actually “a lot of complexity” to why Black lawmakers are less likely to see their bills pass. The issues they prioritize and the environment of the legislature — its party makeup, rules and emotional temperature — all play into it. For Rep. Scott, safety concerns have also made it more difficult for her to do her job at times.

This year’s racial justice movement provided an opportunity for change. There were victories for Kentucky’s Black lawmakers, but it is not clear if gains will continue into the future.

Regardless of the reasons why Black lawmakers’ bills don’t pass, a different and valuable perspective has been almost completely wiped from the statehouse — one that could help Kentuckians throughout the Commonwealth.

“Our’s are the bills that uplift people, take care of people, make life better for folks across the Commonwealth,” said Scott.

The ‘Complexity’ in Why Black-Led Bills Don't Pass

Kentucky’s Black lawmakers all being in the minority party isn’t the only reason that Neal lists for why he and his peers’ struggle to get bills passed, but it is the first one.Because Republicans rule, they decide which committees that bills get assigned to. This year, the supermajority changed the rules so that it could choose not to send a bill to committee at all. If a bill gets to committee, the Republican chairs are the ones deciding whether the bills receive hearings.

Senate Minority Leader Morgan McGarvey said that the majority party, whoever it is, has an “enormous amount of control” in the Kentucky General Assembly.

“If I had the power to get people’s bills called up I would use it,” he said.

But, there are other reasons that Neal gave for why his bills don’t pass. From what he has observed, Black lawmakers tend to sponsor bills that address equity, justice, fairness, race and gender. They have spearheaded efforts to restore voting rights for felons, eliminate the death penalty, raise the minimum wage and more.

House Minority Leader Joni Jenkins said that she thinks party is the main reason why her Black colleagues can’t pass their bills, too, but she also acknowledged that there are bills from Black legislators covering issues that are probably foreign to their counterparts from majority white, rural areas.

“When I came to the General Assembly, women, the numbers of women in the General Assembly, are similar now to the numbers of people of color in the General,” she said. “And I’ve always said that I felt like I was in the minority even when I was in the majority. And I always think, from my perspective, that women back in the ‘90s had to work harder. And now I see that from a little bit different lens that I think I see the people of color, having to work harder to get their bills attention.”

Sponsoring outlier bills also makes it more difficult for Black legislators to form relationships with other lawmakers, said Rep. Reginald Meeks of Louisville, the chair of the Black Caucus. And, relationships are key to passing bills.

Sen. Reginald Thomas of Lexington said that his bills tend to be more progressive. Nationally, Black lawmakers lean more liberal than their Democratic colleagues, and their bills do, too, said Stephen Voss, an associate professor of political science at UK. This includes bills that they co-sponsor. But, Kentucky’s Black lawmakers run the gamut from conservative to progressive, said Kentucky Democratic Party Chair Colmon Elridge. And, Rep. Scott cautions against using the word “progressive” to describe all bills from Black lawmakers. The bills that members of the Black Caucus are promoting are bills that would benefit the entire state, she said.

Meeks agrees that Black-sponsored bills contain something for everyone. “Ironically, many of our issues are also issues that the vast majority of legislators, they resonate back home,” he said. “But, there isn’t anyone or any group necessarily back home who’s touting those issues.”

Even when Democrats held more seats in the legislature, there were issues that Black legislators advocated for that other members of their party ignored, said Meeks, such as making it easier to register to vote.

“Quite honestly,” he said, “there are times when it’s evident that the party itself is not prepared to take the lead, to be bold, to be advocates for all of the party.”

As House minority leader now, Jenkins said that the Black Caucus is an important part of the House Democratic Caucus. One thing she tries to do is ensure that legislators of color are assigned to important committees, such as those addressing education and elections.

McGarvey said that a focus of the Senate Democratic Caucus is equity. There are small things he does to help inch Black-led legislation along. For example, with Sen. Neal’s recent hate crime bill, most Senate Democrats signed on as co-sponsors in a sign of support. It did not pass.

“There’s a disparity there and it’s frustrating and it needs to be fixed,” McGarvey said. “Because I think the General Assembly is designed to represent the viewpoints and experiences of every person in the Commonwealth and to deny hearing so many of our Black legislators’ bills is oftentimes to deny those experiences being heard in the General Assembly.”

Neal, who is also the longest serving senator in the General Assembly, said there was an increase in partisanship in the Senate when previous Republican leadership changed the rules of the chamber to limit minority party expression on bills. Another wrecking ball to bipartisan relationships came when current Republican leadership changed the seating chart in the General Assembly so that Democrats and Republicans were separated, Neal said.

But, Stivers said that it’s actually easier now for Democrats to pass bills than it was for Republicans when they were a superminority.

“When I first came in, Republicans weren’t allowed to pass any bills in the Senate — zero,” said Stivers.

Now, in the Senate, the majority party doesn’t steal the minority party’s bills if they like them, he said. Republicans also introduce the budget earlier in the session than Democrats used to, he continued. And, the seating chart change was not a political move, according to Stivers, but rather an effort to make the legislative process more efficient.

Neal said there are other ways he can influence the legislature in his position as a minority lawmaker. He’ll talk to other legislators about their bills, and he’ll introduce some legislation just to start a discussion. He’s used to being at a disadvantage.

“I don’t feel like a victim,” he said. “I’m not a victim. In fact, I feel powerful in this situation because I understand it.”

A Sometimes Unsafe Environment

For the most part, Sen. Neal has good things to say about the social environment in the General Assembly, from the ‘90s until now.“I think I’ve been treated well, like anybody else,” he said. “For the most part, the Senate is a place of, even when we legislate, you try to promote gentility and respect and a more laidback protocol.”

But, there have been times when he has had to correct other lawmakers when they have addressed him in ways that weren’t appropriate given his race.

“I don’t think they were directed at me to hurt me, but they were words that I couldn’t accept, and I would have to correct who it was right on the spot,” he said.

Some legislators, though, have felt threatened by the actions of their colleagues.

Rep. Scott said she was concerned for her safety during her first year as a legislator, because of the now deceased Rep. Dan Johnson. During his campaign, it came out that Johnson had posted racist photos on Facebook: pictures of Michelle and Barack Obama with their nose and mouths edited to look like apes and another photo of a primate, labeling it as a photo of former President Obama.

“I was, and I think it’s important to keep in mind, I was the only Black woman serving at the time and the only women of color serving at the time which made me a particular target for people,” she said.

Rep. Meeks and Rep. George Brown of Lexington would accompany her through the halls of the Capitol. House leadership never reached out to Scott about Rep. Johnson, and Scott did not reach out to them. But, they did assign Johnson a seat directly behind Scott on the House floor.

Rep. Scott said she has also felt unsafe when armed protesters have come to the Capitol. One time, an armed group surrounded Rep. Meeks while she was walking with him to the Capitol building. They thought he was another lawmaker, one who had proposed a “commonsense gun measure.” Scott yelled at the group that they had the wrong person until they eventually cleared a path for them to leave.

It’s moments like these that Scott said have complicated her role as a legislator.

“I was elected to represent the people in District 41, part of Jefferson County in Frankfort, and it makes it difficult for me to do that in a healthy and safe way when not only am I experiencing threatening situations from people who come to the Capitol from different parts of Kentucky, but I’m also facing it from legislators and facing erasure from legislators so they wouldn’t even know if we were being threatened,” Scott said.

Kentucky State Police, who provide security to the Capitol, did not return a call and email for comment.

This Session's Opportunity for Change

There was a chance this year for the Kentucky legislature to do something different.When the public learned that Louisville police had shot and killed Breonna Taylor, Kentucky joined the list of states with high-profile law enforcement killings of Black people.

“I think all across the country, legislatures are saying, not just in Kentucky but across the country, we’ve got to do better. We just cannot sit by and accept this any longer,” said Sen. Thomas. “Kentucky is no different than a lot of legislatures. We’ve got to address this. This is a problem in our country.”

This legislative session was different. But, in some ways it was still the same.

The legislature passed at least five bills that were, in part, inspired by the country’s racial justice movement, said Stivers. But, most were done with all-white, all-Republican lead sponsors, and — in some cases — contained aspects that several Black lawmakers objected to.

There was Senate Bill 4, sponsored by Stivers, which limited the issuance of no-knock warrants in Kentucky, the type of warrant that was obtained in the raid that ended in Breonna Taylor’s killing. Scott had introduced a ban on no-knock warrants called Breonna’s Law before SB 4, but it did not progress farther than a committee hearing. By the time SB 4 passed, it was ladened with an amendment that carved out exceptions for smaller counties, but it also adopted one of her wishes: for emergency medical services to be present during a raid.

There was Senate Bill 80, which made it easier to decertify police officers. It was sponsored by Sen. Danny Carroll, a Republican and former police officer from Benton.

There was Senate Bill 10, which established a commission in the legislature to study inequities in the state, sponsored by Sen. David Givens, R-Greensburg. Scott called it “performative politics.” Neal and Thomas were co-sponsors on the bill, and Neal told LEO it was a unique attempt by the state legislature to own the issue of race. But, they both dropped their support after an amendment specified that the Prosecutors Advisory Council would have a say in naming a board member instead of the executive director of the Kentucky Commission on Human Rights.

There was House Bill 321, which created a TIF to bring economic development to The West End of Louisville, sponsored by Rep. Brandon Reed, R-Hodgenville. Sen. Neal played a part in creating it. Black lawmakers were split on voting for it.

The last of the five bills that Stivers said was inspired by the racial justice movement, SB 270, was sponsored by a Democrat — Senate Minority Leader Morgan McGarvey. It allows Louisville’s historically-Black university, Simmons College, to receive Kentucky tuition grants and to offer a teaching program.

In his statement, Osborne expressed an interest in tackling more issues of inequity in the House.

“It is clear that we have very real, very grave disparities rooted not only in race but also in poverty,” he said. “This issue has our attention and we will continue to seek input and collaboration to find ways to address these disparities in strategic and intentional ways.”

He specifically highlighted Scott, saying she “played a role in the shaping of the final version of SB 4.”

For Scott, though, the legislative session was filled with frustrations. In addition to Breonna’s Law being overtaken by SB 4, a bill of hers was “literally stolen” by a Republican legislator, she said. Scott’s House Bill 185 would have established maternal and infant mortality teams in Kentucky. One day later, Samara Heavrin, R-Leitchfield, introduced House Bill 212, which would require the state Department of Public Health to keep track of maternal and child fatalities data by race, income and geography. Scott also sponsored House Bill 27, which would have required the Department to track maternal deaths, specifically, by region, race and ethnicity.

Heavrin’s bill passed. Scott’s bills did not make it to committee.

“That was my experience this session,” said Scott.

Heavrin did not respond to a request for comment from LEO.

For Rep. Stevenson, her first year in the legislature was a triumphant one, but it’s not clear what her win means for the rest of the Black Caucus.

Stevenson was assigned to the House Standing Committee on Veterans, Military Affairs & Public Protection. In her committee assignment, she proposed HB 398, and invited a fellow member, Rep. Bobby McCool, R-Van Lear, to be primary co-sponsor.

Stevenson thought from the beginning that she could get the bill passed because it focused on veterans and “nobody likes to vote against the veteran,” she said. Through the legislators she built a relationship with on the Veterans Committee, she was also able to reach leadership and ask them to bring her bill forward.

Her hope is that the passage of her bill means that more bills from Black legislators will pass in future sessions.

“The reasons why all the firsts matter is so there can be a second, a third, a fourth and a fifth,” said Stevenson.

Jenkins is less optimistic.

“I think, to really see a change, you’re gonna have to see people of color in the party that’s in the majority,” she said.

McGarvey said that there are changes that could be made to the General Assembly to make the institution more equitable. For example, bills could automatically receive a hearing if the majority of the members of a chamber sponsored it. He also thinks that the redistricting process should be nonpartisan.

Scott said she doesn’t know if there will be more bills passed by the Black Caucus in the near future.

“That’s really in the hands of the supermajority,” she said. “And what their commitment is to racial justice and equity.”

Data scientist Robert Kahne helped with this story.