Falls City beer is back. It isn’t quite the same as it always was, but it may be closer than we think. There are reasons for that, and like always, it’s best to start at the beginning.

Teddy Roosevelt was living in the White House in 1905 when Falls City began brewing in Louisville. Most other local breweries of the day, including the makers of such famous brands as Fehr’s and Oertel’s, were family-owned businesses, but Falls City was a company conceived and operated by investors who came together for the express purpose of combating an existing local sales monopoly.

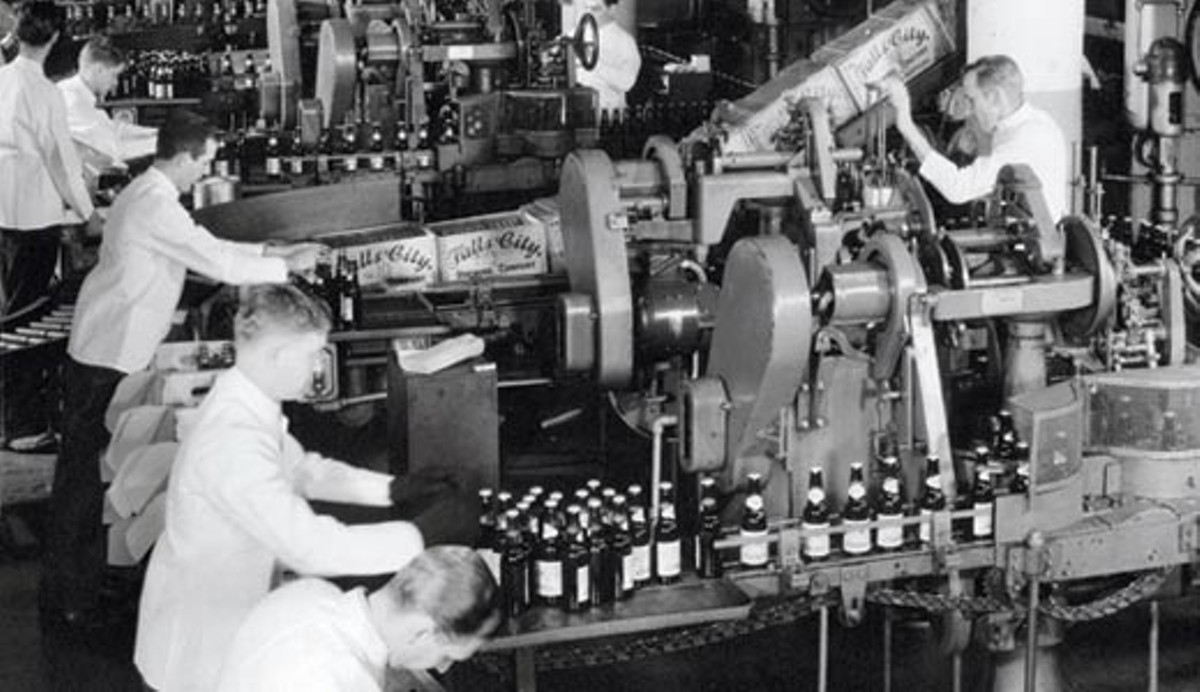

In short, the original Falls City was built to last and intended to be a sizeable regional player. It succeeded on both counts, cleverly diversifying to survive the shameful time of Prohibition, and reaching its zenith during the post-World War II era. Unfortunately, the eventual market dominance of national and international brewing conglomerates eroded Falls City’s sales position, and in 1978, the company’s last board of directors dissolved.

The Falls City brand migrated to other owners and was inelegantly bastardized as a cheap-budget brand before being orphaned. Then it was acquired by David Easterling, an entrepreneur with revival on his mind. I interviewed him at a recent expo at River City Distributing, his wholesaler.

LEO: Why Falls City, why now, and why you?

David Easterling: Falls City Beer is as much a part of Louisville history as the Ohio River or Churchill Downs. Everyone who grew up here has a story about their dad or granddad (or in some cases, grandma) drinking FCB. I just saw an opportunity to bring new life to a great piece of Louisville history and took it.

LEO: Most people who ever drank Falls City recall it as a lager, of a style we now refer to as “pre-Prohibition,” made with six-row barley and corn. Given the brand’s cheapening and decline in later years, it’s a safe bet that not everyone remembers it fondly. What are you up against, and is that why you’ve reformulated Falls City as an ale?

DE: People often ask why it isn’t like the “old” Falls City — well, technically it is. Falls City made a variety of beers early on, and one of them was a Pale Ale. I thought it would be easiest to introduce that style first, so there could be no thought that I was trying to replicate the last version of the lager. One taste of the new brew, and you know you’re drinking a great beer. There is a good niche in the market for our style of beer, too. American Pale Ales (APAs) are a little hoppy for the average lager drinker and not especially sessionable. The new Falls City is more accessible than an APA but has the body and flavor that craft drinkers are looking for.

LEO: When the original Falls City closed in 1978, it was the last remaining brewery in Louisville, although the brand lived on, brewed first in Evansville and later in Pittsburgh. Where are you brewing it now, and are there any plans to brew Falls City in Louisville?

DE: I am contracting with a small brewery in Cincinnati right now. The plan is to brew in Louisville eventually. I need a little more market data before I know what kind of investment to make in a brewery. So far, sales have exceeded expectations, so I’m optimistic we’ll be able to brew here sooner rather than later.

LEO: I suppose Billy Beer is to remain safely buried?

DE: I don’t see us brewing Billy again. Billy lives on in basements across Kentucky, though. I don’t think we’ve seen the market peak for full cans of Billy Beer.

LEO: Can you tell me a few places that have your new Falls City on draft?

DE: Working with the bar owners, managers and bartenders in the bars that carry Falls City has been the most fun part of this venture — and an unexpected bonus. There are currently around 30 bars and restaurants that have us on tap. They have really been supportive and patient as we’ve tried to keep up with demand. The full list is on our website (fallscitybeer.com).

The writer thanks Conrad Selle and Peter Guetig, authors of the seminal “Louisville Beer.”