This was to be a simple exploration of the gap between art money and Black artists. It sounds so naive. Nothing about the Black experience in America is “simple” and the places where we go to work through our traumas, to dream, to manifest — our arts — are as fraught as the nation we try so hard to be part of.

This issue, like all the others, is an octopus, a hydra. There are simply too many heads, too many arms and too many ways to wrangle the centuries-old mess of white supremacy and racism and what that has done (is doing) in this nation, even at the level of local and public arts. So there is no reason to force it. It will take the time it takes.

This week, I talked to two artists — who also happen to be Black women. One a researcher, visual and teaching artist Marlesha Woods, who is working on a project with Root Cause Research Center and the other, Toya Northington, an educator, artist and community engagement strategist with the Speed Art Museum. We talked about the original issue, the arts wealth gap, quickly acknowledging that there is no small way to approach the subject.

“We haven’t even gotten to the wealth gap,” said Northington, noting the historic economic disadvantage that Black people and Black artists have in America. “We’re still in survival mode.”

Setting some contrast and talking about the art world of the elite where the millions live and then zooming in on how that looks here in Louisville is a good place to start.

The “art world” of the glitterati is booming with dollars, taking in $64.12 billion dollars in 2019. This “art world” is the Wall Street, suit and tie set calling itself, THE art world. It exists to give very wealthy people the access to beautiful images, creations, performances and sometimes access to the creators. This lets rich patrons feel more interesting, hide their money, or decorate obscene palaces around the world. This art world is the one that let Andy Warhol thrive and make fun of it at the same time. It’s the art world that makes the Rococo-style ceramic, “Michael Jackson and Bubbles” by Jeff Koons, nearly priceless.

In this “art world,” sales reach into the hundreds of millions of dollars. The artists involved are often deceased or cut out of any resale residual money. They are also mostly white. If you are a Black artist and aren’t Jean-Michel Basquiat, then you remain invisible.

The thing is, ultimately, most artists — white or Black — aren’t ever going to fit in that world. In fact, most artists don’t live on simply making art.

“That’s like the dirty little secret of the art world,” said Northington. “It pits us against each other as Black creatives because when you see somebody out there and see them exhibiting and people kind of coming up in the art institutions, you think, ‘Oh they’ve got some money.’ They don’t have any money. They have some reputation and their art is out there, but they are not far from you.”

In the city of Louisville, private donors and institutions both public and private help fund public art projects, sometimes awarding large contracts to the creators. Some of those creators aren’t local artists, though the capacity to create these works does often exist locally.

For Black artists in Louisville, getting one of these contracts is rare, and when they come through, are often awarded at a much lower rate than white counterparts. Some aren’t compensated at all.

Marlesha Woods’ research looks deeper at this local gap, because it isn’t just a difference in dollars and cents, it is a gap of metrics. The metrics of survival versus the metrics of who gets invited to the table.

“The racial wealth gap is not solely tied to dollars,” said Woods, “but lived narratives that reveal generational trauma. I am confident that no matter what access, opportunities or achievements have resulted from the diligence of carving out pathways to thrive in the U.S. and globally, no racially-identified minority lives, works and dies, untouched by that trauma. The question is how to get free and stay free.”

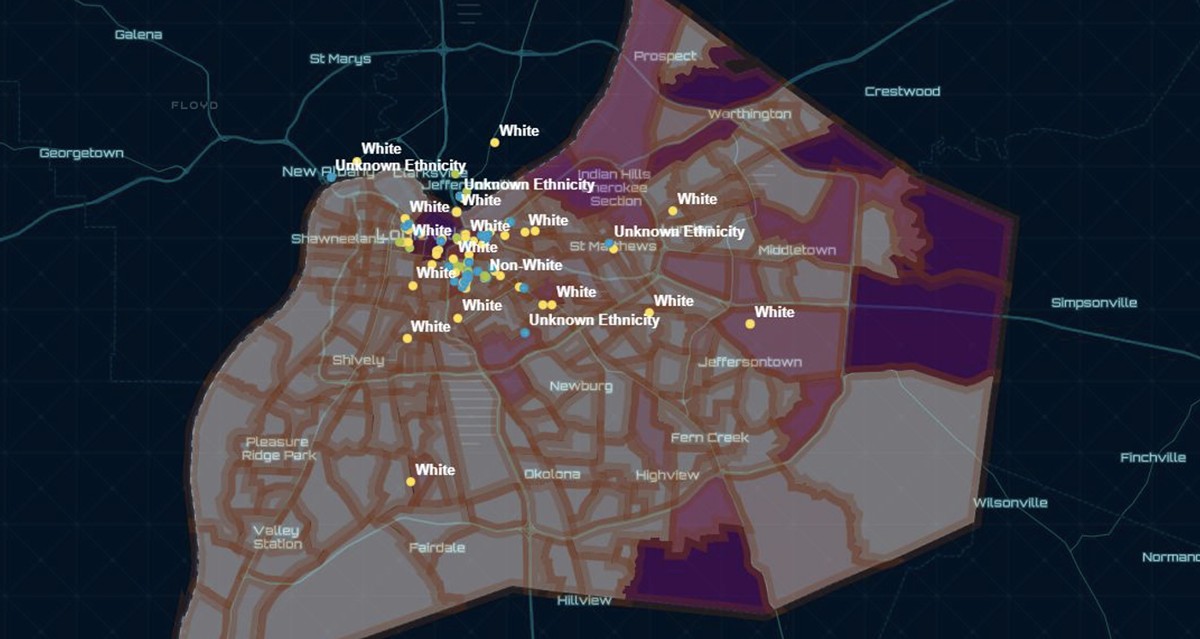

Woods’ current research, “Art Embodied: Immeasurable Paint,” in conjunction with Root Cause Research Center focuses on what she calls the “Immeasurable Paint” of Louisville. It is an exploration both of the gap in funding but also how public art can reveal erasure.

In Louisville, while “paint” (public art and murals) covers the city, it is often who is doing the painting and getting the contracts for those projects that tells a bigger story about the financial breach between Louisville’s white and Black creative communities.

“If you’re a West End resident and an amazing artist and have everything in line, you want to propose something that’s going to happen in your neighborhood. That’s great,” said Woods. “That’s not the key. It’s also cool if you have the same access, the same opportunity, the same equal opportunity to paint downtown Louisville, paint East, to paint Prospect. You don’t have to be just stuck in, ‘Oh, the Black people can have a paintbrush over here so we can give them a little bit of dollars.”

“The point is that if you’re competent, capable and you’re talented, you should be able to have a shot,” she continued. “There are people who have had shots for years that didn’t even need to have a pitch meeting for a grant, and they’ve gotten multiple grants. A lot of them are run out of the same organizations over and over again.”

A simple investigation of the interactive StoryMap on the RCRC’s webpage shows where the “paint” is and who the artists are that were given permission and/or contracts to do these public projects. Hovering over the points on the map will reveal the artist or artists’ identities.

And, while many of our larger arts institutions and entities have made promises — and few tangible steps towards equity in these areas — visibly, the chasm hasn’t narrowed.

“The worst promise that has happened is...that we’ve had so many broken promises, at some point, you become hopeless,” said Northington. “So when you’re exposed the opportunity, you don’t even believe it.”

Northington compares this cycle to classical conditioning with mice and cheese. There are only so many times a mouse is going to receive a shock before it gives up on eating the cheese. This is a good reflection of Black artists and their relationships with local arts entities.

“That happens to us over and over, and we lose that drive” she said.

The question is, how do promises become reality so that this gap truly closes and how do Black artists begin to trust and take the “cheese?” •