[Ed. note: This is a throwback, timeless column, first published Nov. 24, 2004 by LEO’s founder. Unfortunately, the issues he raises are perhaps even more relevant today.]

Let’s give thanks for our friends. Friends bring joy to our lives, help and support when we need them and, optimally, reinforce our interests and our values.

This is a difficult period in American society, when many of our traditions and relationships are being severely tested. Politics is no longer merely a quadrennial competition like the Olympics. For many of us, campaigns and elections have become important attempts to validate our core beliefs. To wit, we take these things very personally.

Not many relationships are threatened by disputes over trade and tax policy or even by the war in Iraq or the Patriot Act. But other issues force us to reflect not only on what we think, but also on what the people we love think.

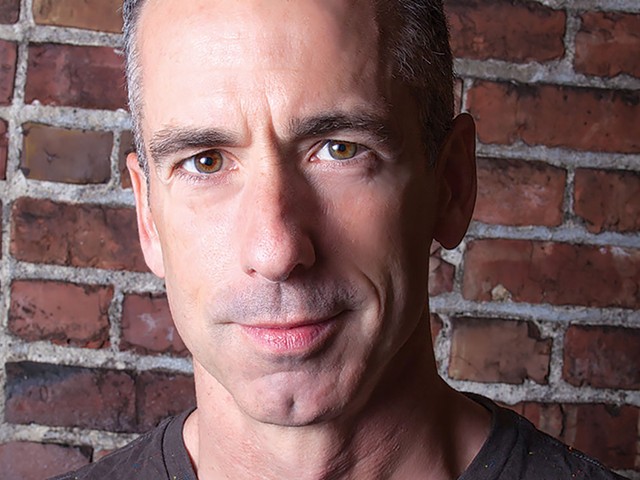

Last week, I received a letter about my columns from a longtime acquaintance, once a friend, but now only someone I’ve known for decades. Part of the letter read: “You make much of the gay issue. I don’t. Gays are on the outside margin of American society. My wish is that they stay there.”

One of my best friends is gay. He, his partner and his gay friends are terrific people. He is one of many gays and lesbians I know, like and respect. They are very much inside the margin of American society. They work, pay taxes and enhance the vitality of their communities. So how do I regard someone who wants them marginalized? Can I be friends with someone whose values are so different (or conversely, I guess, he with me)? What would be the point?

Much has been made this year about the eagerness of both sides of the political equation to demonize the other. Liberals have criticized Bush supporters as stupid Bible thumpers and conservatives have criticized liberals as arrogant, effete, amoral libertines. This isn’t a “tastes great, less filling” argument in which both sides are right, although in some individual cases the mutual charges are pretty accurate.

When you get past the nuts and bolts of government — issues like roads, Social Security and defense spending — politics and relationships are all about values. And while both sides do too much name calling, there can be legitimate, values-based justification for not respecting someone with whom you have a fundamental conflict.

So, what does that mean for politics? In the aftermath of this year’s election, we losers kept asking a seemingly unanswerable question: How could a president be reelected when a solid majority of the American public thought the country was headed in the wrong direction? Turns out, the answer is fairly obvious; many of those Americans weren’t thinking about public policy when they answered the question.

When more than one-fifth of voters said they voted on the basis of moral values, they weren’t talking only about abortion and gay marriage. They were talking about “Desperate Housewives,” Janet Jackson, Scott Peterson, Ron Artest and all sorts of people acting badly. And they voted for the candidate who they perceived to best represent the “values” most important to them.

Liberals for some reason seem to be afraid to speak out against Janet Jackson, “Desperate Housewives” or reality TV even if we are offended by them. We are so afraid of censorship that we accept things we know are clearly value-deficient. If I’m right, progressives have an enormous opportunity. We — and the Democrats if they choose to come along for the ride — don’t have to cozy up to neocons on values. We don’t have to move closer to them on abortion (where we already agree with the majority), public religion and gay marriage. We can start using whatever bully pulpits we can find to do some preaching of our own. Forget about Bush and the Republicans. We should talk about the junk programming that mega-corporations are giving us on TV, about the unhealthy food that is being marketed to our kids, about the pollution that we have to breathe and about the gas-guzzling cars we are driving. We can talk to citizens about their power, outside of government, to impose their values on society. (One thing liberals should have learned over the last 20 years is that public pressure changes things much faster the government.)

If we’re right on these issues and on issues like health care, economic justice and tolerance, we ultimately won’t need to win elections to prevail. If we’re wrong, we won’t deserve to win elections. And most important, we won’t have to waste time and emotional energy trying to convince people like my former friend that our values are right. We’ll just keep talking until he is marginalized.

Happy Thanksgiving.