A sepia-toned photograph of a woman seated in front of a barn hangs on one wall inside the office of Kentucky state Sen. Gerald Neal. A slave born in 1839, the woman is Margaret Dean, Neal’s great, great, great aunt, who reached the age of 103, outliving the institution of slavery into which she was born.

In stark contrast to the historic family photo, a giant poster of the TIME Magazine cover featuring newly elected President Barack Obama leans against a bookcase. On the top shelf there’s a framed photograph of Neal’s father, Sterling Neal Sr., a leading union organizer in Louisville who was inducted posthumously into the Kentucky Civil Rights Hall of Fame in 2003.

Each piece of memorabilia adorning Neal’s office inside the state capitol is accompanied by a story. It’s a collection Neal has continued to expand since he was first elected in 1988, replacing Georgia Powers, a civil rights icon who became the first African-American and the first woman elected to the state Senate in 1967.

But it’s the weathered photograph of his slave ancestor that reminds Neal — Kentucky’s only black state senator — how far this nation and this state have come.

“She’s the one that we can go back furthest to in our family,” Neal says. “It ties not only various branches, but we see ourselves as a continuation of her and those before her.”

The highest-ranking black elected official in the commonwealth for the past 20 years, Neal represents a district that includes a sizeable portion of Louisville’s West End. Residents who protest about that community’s economic and social problems are abundant, but few blame Neal, who has gone largely unchallenged in repeated elections.

It’s almost 10 a.m. on a recent Thursday and the day’s business in Frankfort is already in full swing. Dressed in business attire, about half a dozen students from Neal’s Kentucky Politics & History course at the University of Louisville (where he teaches part-time once a week) are visiting Frankfort as part of a class requirement. Standing around the cluttered conference table in Neal’s office, the students are expecting a personal tour of the capitol from a man who fancies himself a history buff. But Neal is already swamped and running behind, so it seems there might not be time for that today.

A judiciary committee meeting is scheduled to begin in a few minutes, and Neal tells the students he’ll meet up with them later at the day’s legislative session. Grabbing his gray suit jacket from the coat rack, he marches out of the office suite he shares with three other senators.

Although running late for his meeting, Neal stops on the way to chat informally with Sen. Dan Seum, a well-known Republican from south Louisville.

“Relationships are crucial,” Neal explains as the two part ways. “We’re on opposite sides of just about everything, but we can deal.”

The maze of hallways is filled with fellow lawmakers, lobbyists, tourists, students and Senate aides, and the belly of the capitol annex is grumbling with constant backslapping.

As Neal searches for the right committee room, he is stopped several times by someone seeking a vote or a handshake. A teenage girl approaches with a clipboard hugged tightly to her chest. She is lobbying for legislation to strengthen Kentucky’s domestic violence laws, and she gives a nervous but rapid-fire explanation before asking the senator for his support.

“I’ll take a look at it,” Neal says, perching his glasses at the edge of his nose to examine her brochure before heading into the meeting.

The bills being considered by the Senate judiciary committee include a handful of acts relating to crime and punishment, controlled substances and child medical support. Neal remains quiet but attentive, until finally he speaks up to inquire about a bill offering more funding for Kentucky prisons. Senate Bill 76 would require that each county receive $30 per prisoner daily for the care and maintenance of state prisoners housed in county jails.

Given these tough economic times — Kentucky’s budget deficit is some $456 million this fiscal year, which ends June 30 — Neal is skeptical, but does not voice outright opposition. Later he explains, “The budget trumps everything this session.”

About an hour-and-a-half into the laborious committee meeting, Neal introduces a proposal to continue studying possible reforms to the Kentucky Penal Code, which he calls “disjointed and irrational.” It’s one of a handful of bills he is sponsoring or co-sponsoring this session, including one to develop an intensive substance abuse recovery program for prisoners and another to restore voting rights to convicted felons, the latter of which has been championed for years by social justice organizations.

Whether in committee meetings, roaming the capitol halls or on the Senate floor, Neal is often the only African-American in the room. This does not seem to bother him, as evidenced by his calm and confident swagger.

“I don’t think or move like that,” Neal said during a recent telephone interview. “The work I do is not for myself — I’ve done pretty well. It’s for those people who have been compromised by our historical and lagging cultural development.”

Although Neal might not think about race when dealing with his colleagues, the fact that he remains one of only a handful of black elected state officials in Kentucky certainly raises questions about whether this cheerleading regarding a post-racial America is warranted, particularly here in the bluegrass.

“If you really look around the political landscape of America you still see at this point African-Americans faring very poorly as far as statewide offices are concerned,” says University of Louisville political science professor Dewey Clayton, who specializes in race and government.

That’s also apparent on the federal level, where the majority of black elected officials represent congressional districts. Of the 43 members of the Congressional Black Caucus, for instance, all but one are in the House of Representatives. And Massachusetts Gov. Deval Patrick is the only elected black governor of any state.

And while Clayton acknowledges the election of President Obama presents new possibilities for African-Americans, Kentucky still has a lot of catching up to do.

The commonwealth’s black population hovers just below 8 percent and is concentrated in a handful of metropolitan areas. Currently there are six other African-Americans who join Neal in the General Assembly, but they represent even smaller house districts across the state.

Clayton says there are many reasons Neal remains the lone black face in the state Senate; chief among them is Kentucky’s history of racially polarized voting patterns. But demographics should not be an excuse for a lack of diversity in the legislature, according to Clayton.

“It’s a question of political maturity. If we’re going to win statewide elections you have to play a different game of coalition politics,” Clayton says. “Until then we’re going to be confined to representing black majority districts only, which in Kentucky, with a small black population, that’s going to limit your opportunities.”

The 33rd senatorial district represented by Neal includes neighborhoods from Shawnee to Clifton and is about 53 percent African-American. Regardless of a district’s makeup, Clayton says black candidates ought to test the waters even though African-Americans have historically been excluded from the political pipeline.

Kenya McGruder, former state director for the Obama campaign in Kentucky and president of the Urban League Young Professionals, says she has encountered a number of young African-Americans interested in running for public office, particularly since Obama emerged on the national stage.

Remaining hopeful, McGruder says the possibilities are endless now that Obama is in office, but the burden can be daunting and is not solely on African-American communities or would-be candidates.

“Anybody can win any seat. I will always believe it can be viable if you run hard and get a good team,” she says. “The reverse question is whether the Kentucky Democratic Party is seeking out viable African-American candidates to get into these seats.”

Charlie Moore, named director of KDP last week, said the party isn’t specifically targeting African-American candidates, but that the legislature should better reflect the racial breakdown of the state’s population.

By late afternoon, Neal is hustling between the Democratic caucus room and the Senate floor. There are only a few substantial bills being considered today, so business quickly turns into a parade of procedural resolutions and formal introductions.

Earlier in the day Neal arranged a photo-op for his U of L class outside the rotunda with Gov. Steve Beshear. Now he is formally introducing the students to his colleagues on the Senate floor.

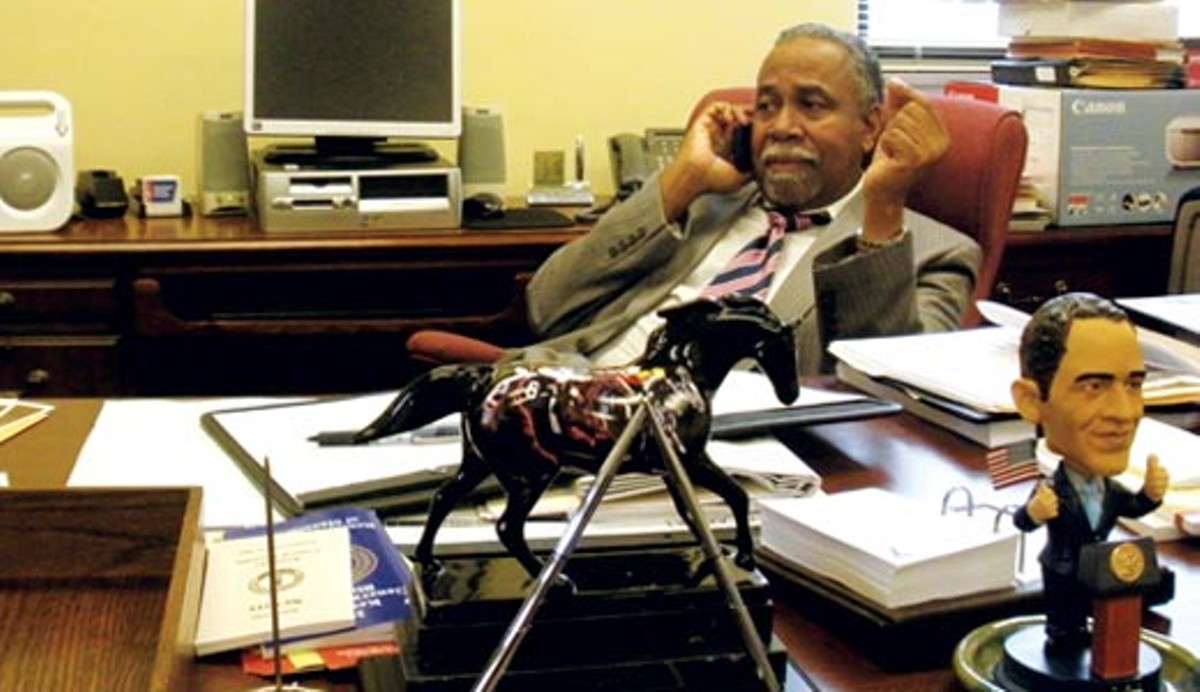

Walking through the underground corridor that connects the capitol to the annex building, Neal eventually returns to his office. Loosening his tie, he settles in behind a massive wooden desk and begins to reminisce. He recalls his college days in the 1960s when he was a student activist, marching on picket lines and engaging in civil disobedience (including a bold stunt that involved taking over the office of U of L’s president at the time).

Since then, he says the state has made significant strides toward racial equality. And although he made his way to the Senate, a struggle remains.

“There was certainly a significant group of people who resisted. And that resistance now is structural,” he says, citing troubling statistics regarding minorities and education, employment and incarceration rates in Kentucky. “Even with Barack Obama, when you really look at the voting patterns, sure it reflects some change. But there’s also a very difficult, historical resistance racially. Twenty percent of the people in the primary said they wouldn’t vote for a black man — well, that’s Kentucky.”

As he speaks, his office phone rings, interrupting his thought. It’s a colleague calling to discuss politics. Neal leans back and outlines a strategy. It’s back to business.