So, OK, history is not likely to place our more local heroes Daniel Boone, John Floyd, George Rogers Clark and Ohio and Missouri river travelers Meriwether Lewis, William Clark and Clark’s slave York in the same canoe with Donald Trump. It would be kind of like an orange with a bunch of apples. The Donald would talk a lot and never touch a paddle.

But in the Big Picture of American journeys — and the recent presidential election only adds more proof — there is some comparison: Most of these men started out pretty well and then fell out of the canoe. Boone, Floyd, Lewis, the Clarks and York all made a regional if not national impact — some of that still enduring today with the help of Hollywood, Walt Disney and Netflix. They made a difference. The United States got a whole lot bigger. We just never learned enough about the often-sad rest of their lives in our history classes — with William Clark, George Rogers Clark’s younger brother, coming out the best.

Their stories are separated from Trump by a few centuries, six bankrupt gambling casinos, a self-serving TV show, three wives, a horrendous virus and a Russian premier, but ego, arrogance, stupidity, childish behavior, adoring followers and eventual fall from grace are universally available in the leadership of any generation. History does roll in a full circle. Some day we may learn from that. All politics is local — and national. Trump leads the pack, but most of those men ended up as various degrees of losers: broke, damaged, forgotten, unelected and case studies in failure, although certainly not all of their own doing.

Closer to home the downside of our Indiana, Louisville and Kentucky pioneer figures include: Terrible businessman, victim of politics and land speculators, drank too much and fell into a fire, had a son tortured by Native Americans, trapped in slavery, captured by the British, killed by Native Americans, buried in unmarked graves, committed suicide. All that has generally been saved for at least the fourth or fifth paragraphs of their biographies.

Most of these pioneers were in some way aware of the other; some even drank, traveled and fought together. Some achieved considerable early fame — but rarely fortune — even as their incredible deeds contributed to our larger American history and westward expansions.

Donald Trump’s future — as the saying goes — is still ahead of him with the one certainty he did not, despite all he doth protest, win reelection. The 72 million votes received and those who offered them will cast a long shadow over the land but, as a recent story in The New York magazine by Jane Mayer surmises, Trump’s troubles and decreasing fortune are still ahead of him.

He has survived one impeachment, two divorces, six bankruptcies, 26 accusations of sexual misconduct and an estimated 4,000 lawsuits.

During his coming years of awkward seven iron shots at Mar-a-Lago he is looking at $300 million in personally guaranteed loans that need be paid, about $900 million in real estate debt, a few possible IRS rulings that could cost another $100 million if not easy time in the slammer and the declining value of said real estate.

Some think he has no interest in the presidency but can’t afford to get out. Others think him the next Rush Limbaugh — but too lazy to work three hours a day at the job. A few see him leaving the country. Many wish he would leave the country. Millions more want him to stay and Make America Great all over again in 2024. Ahead lies the possibility he may try to pardon himself. All that and his niece, Mary Trump, in her book “Too Much and Never Enough” called him “a terrified little boy.”

But it is interesting — if not educational — to compare past fallen heroes with our new ones. With the help of the Filson Historical Society’s Jim Holmberg, let’s go back a few hundred years to list the living truths and final tragedies of our early soldiers, settlers, explorers, agents, slaves, bureaucrats and politicians who gave us Louisville, Kentucky and Indiana before fate, turmoil or Native American musket fire did them in. And before Donald Trump got elected and took his turn at failure.

DANIEL BOONE

Boone, the sixth of eleven children, first reached Kentucky — then a part of Virginia — from his home in North Carolina in 1767 on a long hunt with his brother, Squire Boone. He returned in 1769, was captured by a party of Shawnee Native Americans who took all his furs and strongly suggested he not return. Boone, of course, did return in 1773 to lead a group of about 50 settlers into Kentucky where Native Americans captured his son, James, torturing him and a companion to death. The party quickly returned to North Carolina.

The killings led to a war with the Shawnees, which Boone joined, being named a captain in the militia. At war’s end, Richard Henderson, a prominent North Carolina judge and land speculator illegally purchased from the Cherokees a monster tract of land that’s now Western Kentucky and part of Tennessee. Calling it the Transylvania Purchase, in 1775 he hired Boone to lead 30 early settlers along what became the Wilderness Road through the Cumberland Gap to Boonesborough.

Kentucky was a dark and bloody ground in those days. In 1776, Boone’s daughter, Jemima and two other teenage girls, were captured outside Boonesborough by a Native American war party. Boone and others, including one John Floyd — and hold that thought — took off in pursuit, ambushed the Native Americans and saved the girls. The warfare continued, and in 1778 Boone and 30 others were captured by Shawnee Native Americans. Boone negotiated a settlement, lived with the Shawnee a few months before escaping. He was subsequently court martialed for leaving the other captured men behind. He was found “not guilty,” but was humiliated in the process.

In 1780, Boone joined up with General George Rogers Clark — another name to remember — in the American Revolutionary War to fight the Shawnee-British forces, battles in which two more of his sons were killed. At war’s end Boone bought a tavern in Virginia, became a surveyor, horse trader, politician and large-scale land speculator, dealing with parcels as large as 10,000 acres. He also owned seven slaves. The 1780s land market was very chaotic, poorly surveyed and ripe for large financial failures, including Boone’s. The explanations for those failures varied from Boone being incompetent to too trusting of other dealers.

“Many of the early guys,” said the Filson Society’s Jim Holmberg, “didn’t necessarily follow the needed land laws of getting the warrants, the surveys and everything else down to the final grants and ownership. The land that Boone claimed, all of a sudden, wasn’t his anymore.”

Boone did strike it rich in history book fame, however. In 1784 historian John Filson — the guy for whom the Filson Historical Society was named for — wrote a glowing, optimistic, come-on-out-here book about Kentucky featuring the life and adventures of one Daniel Boone. The book sold well and went international, selling in French and German. Filson, by chance, also owned large tracts of land in the area he so touted to others.

As Kentucky became a state in 1792, Boone became a living legend. He returned to Kentucky in 1795 with his wife, Rebecca, with whom he had shared 10 children over 25 years. She then adopted six more of her widowed brother’s family. Boone’s fame was no help in creating a fortune. He bid on and lost a job to widen the Wilderness Trail into a wagon route — the very trail he had opened. His Kentucky land claims were sold off to pay legal fees and taxes. In 1798, a warrant was issued for his arrest after he ignored a court summons. That same year Boone County was named in his honor.

Fed up with all of it and wanderlust still in his soul, Boone in 1799 moved to what became Missouri, then still part of Spanish Louisiana. Once there he acquired some large Spanish land grant territory, all of it on verbal promises he would become a citizen of Spain and swear allegiance to its king.

“Supposedly,” said Holmberg of the move west from Kentucky, “Daniel Boone said ‘I will never set foot in that damn state again.’ And there’s no evidence that he ever did. I think he just felt he’d gotten kind of a raw deal.”

With the 1803 Louisiana Purchase — and with no written record of his Spanish land grants — Boone lost much of that land, too. After petitioning the U.S. Congress he got it back about ten years later. He then sold some of that to pay off Kentucky debts.

Rebecca Boone died in Missouri 1813. Daniel Boone was five weeks short of 86 in 1820 when he died. He was buried in an unmarked grave — common at the time — until 1830. In 1845, as Boone’s fame and legacy grew, a Kentucky delegation went to Missouri to dig up the bones of Daniel and Rebecca and bring them home to a Frankfort cemetery. Holmberg said a debate continues to this day if the right bones were moved back home to Kentucky — a place Boone didn’t want to see again anyway.

“Missouri disputes it,” Holmberg said of Boone’s bones being moved, “and Kentucky says, ‘yeah.’ That Frankfort grave. Boone’s in there.

“Some people have done some limited testing. They did a cast of his skull, which we have here at the Filson, but there’s a dispute, even among the forensic people, as to whether it’s the real deal or not.”

JOHN FLOYD

In 1774, just a few years after Daniel Boone first came into Kentucky to help settle disputed lands illegally purchased by Richard Henderson, Virginia-born John Floyd and a party of surveyors set out downriver toward the Falls of the Ohio to also try to resolve those issues. Floyd had the experience; he had lived and worked for Col. William Preston — think Louisville’s Preston Highway — and had surveyed for a couple patriots named Patrick Henry and George Washington.

He was 24 when he and the others were first to survey the lands around the Falls — including what would become Louisville. Along the way, Floyd claimed 2,000 acres in now what’s now St. Matthews and Bowman Field. On June 13, 1774, wandering south, the party came across a small river and named it Floyds Rivers — now Floyds Fork — think of the 4,000 acres of the Parklands of Floyds Fork in Eastern Louisville.

Floyd would later claim the only reason settlers stayed in bloody Kentucky was Native Americans had stolen all their horses and the Ohio River only ran one way. Indeed, Native Americans attacked his survey party, killing two men as four others fled down the Ohio and Mississippi rivers to safety. Floyd, alone and on foot, made his way back to Virginia on a 16-day overland journey. He, of course, returned to Kentucky in 1775, leading a party of 32 men through the Cumberland Gap, setting up camp only 20 miles from Boonesborough.

He was a delegate to Boonesborough at which the Transylvania colony was founded, made friends with Daniel Boone and joined him in that 1776 rescue of his daughter, Jemima, from the Native Americans. Floyd returned to Virginia and, with no maritime experience, signed on to a privateering syndicate to command the USS Phoenix to plunder British commerce during the Revolutionary War. His ship was captured by the British. Floyd was taken to England, escaped prison, was shuttled to France where American Ambassador Benjamin Franklin helped him get back to Virginia.

He returned to the Falls of the Ohio in 1779 with a new wife and son and five siblings to reclaim his 2,000 acres and establish settlements along what’s now Beargrass Creek. George Rogers Clark convinced Gov. Thomas Jefferson to name Floyd as Colonel of the Kentucky Militia in charge of Louisville’s defense. Floyd was also one of Louisville’s first trustees and Justice of the Peace; the earliest Louisville leader.

The local wars continued. Floyd and Clark engaged in several Native American battles, the most ignoble near Eastwood, Kentucky in September 1781 and labeled “Floyd’s Defeat” as 17 men were killed or captured. In April 1783, Floyd was wounded in a Native American attack on his way south to Bullitt’s Lick and died in a nearby stone house. He was 33. He would be buried in what’s now the Floyd-Breckinridge Cemetery on a hill just above noisy Interstate-64 and behind the Jamestown Apartments complex off Breckenridge Lane.

That cemetery and gravesite were initially abandoned and forgotten, even trampled by cattle, before the development of St. Matthews. It was resurrected in the 1940s by the Filson Historical Society; a stone wall built around it; Louisville history held in place.

GEORGE ROGERS CLARK

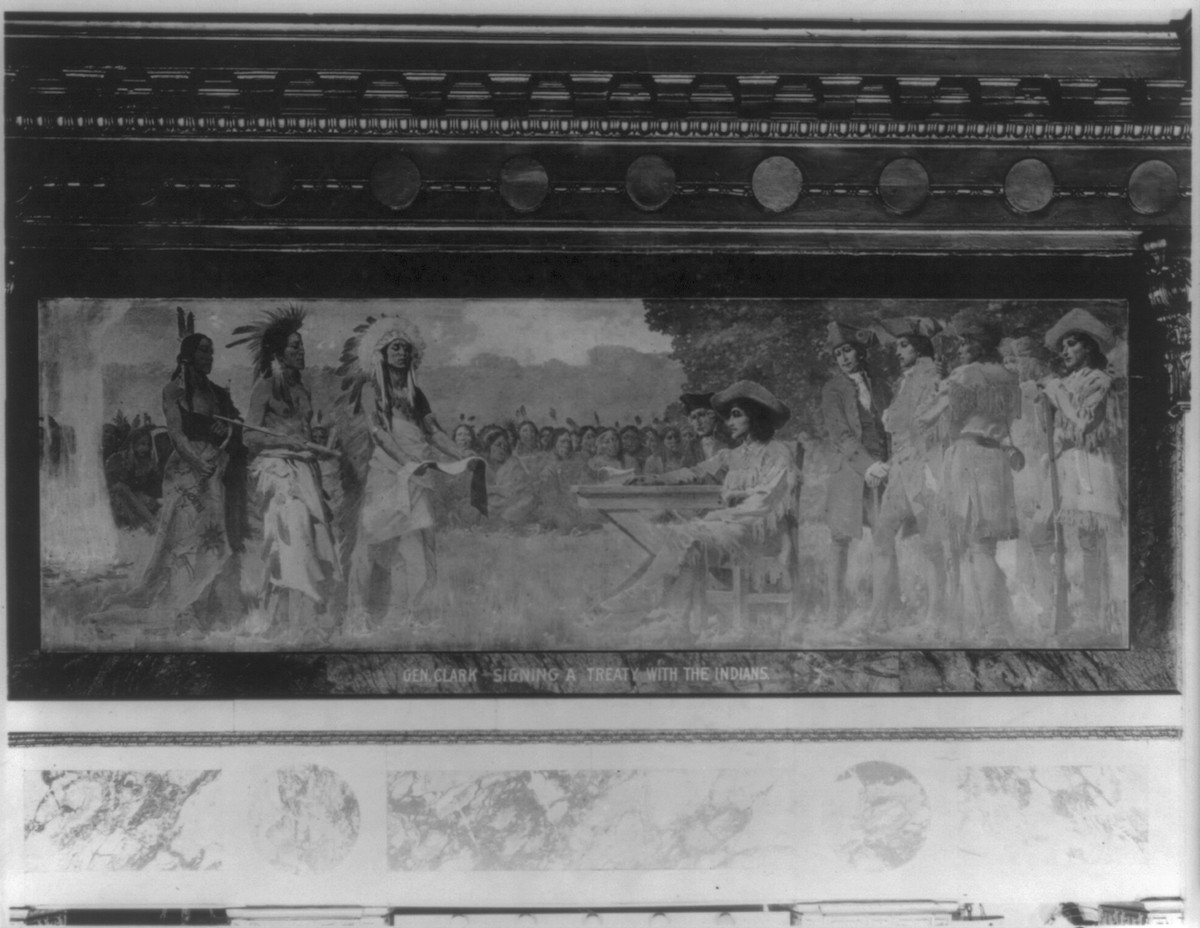

You already know the connection between George Rogers Clark, himself a surveyor, to Daniel Boone and John Floyd. If you were paying any attention in history class you are aware that Clark, at age 24, led 175 men on the secret Illinois Campaign in 1778 and 1779 during the Revolutionary War. In brutal winter weather his small party captured several British-held villages, eventually helping to add the entire Northwest Territory to our national portfolio, now Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin and part of Minnesota.

Clark’s major problem with that campaign — and a couple others — was government money from Virginia was scarce and he ended up financing a lot of it himself. He went on to fight several successful battles in Ohio, then returned to Louisville where in 1781 Virginia Governor Thomas Jefferson promoted him to brigadier general and placed him in charge of all Kentucky and Illinois militias. Most important to local history, Clark’s original party down the Ohio included about 60 civilians who set up camp on Corn Island at the Falls of the Ohio. In 1778, the settlers moved over to the mainland and established Louisville as Corn Island slowly washed away.

Frontier life remained difficult. About 1,500 settlers had been killed in the 1770s and 80s in Kentucky. Clark remained in the fighting as rumors began to circulate that he was often a drunk and ineffective leader. He also had financial problems. Neither Virginia nor the United States Congress had paid him back for his military expenditures, although his wartime compensation did include a 150,000-acre Southern Indiana grant that now includes Clark County and parts of Floyd and Scott County.

In desperation, Clark offered his services to the French, who were in disputes with Spain along the Mississippi River. Using his limited funds and money borrowed from friends, Clark was prepared to create an army and seize St. Louis and New Orleans when George Washington called the whole thing off.

Debt, bitterness, political rivals and alcohol eventually drove Clark to a cabin and little piece of land on Clark’s Point in what is now Clarksville. It was there that William Clark — George Rogers Clark’s younger brother and financial savior — would meet with Meriwether Lewis to discuss their Thomas Jefferson-inspired “Corps of Discovery” to the Pacific. The site is now the Falls of Ohio State Park.

George Rogers Clark had one more possible chance at financial success. He was named a board member of the Indiana Canal Company, which in 1809 was chartered to build a canal on the Indiana side of the Ohio. The venture collapsed a year later when two fellow board members, including Vice President Aaron Burr, were arrested for treason with some of the $1.2 million in investment missing.

“By then,” said historian Jim Holmberg, “Clark was leading a pretty quiet life, engaged in history, corresponding with some folks, but he was getting crippled up with rheumatism. Other people would write his letters for him because his hands were getting so crippled with arthritis.

“And then, in 1809, he is either drunk, had a stroke or rheumatism in his hip got to him and he falls into the fireplace in his cabin. His right leg is burned so badly gangrene sets in and it has to be amputated.”

The story is that Clark, without anesthetics available, called for a fife and drummer to play a tune outside his window and tapped his fingers in tune as the leg was sawed off. He lived the next nine years at Locust Grove in Louisville with his sister, Lucy, who had married Major William Croghan.

Clark died in February 1818 and was buried in a cemetery behind the house on Mulberry Hill, now George Rogers Clark Park. His body was moved to Cave Hill Cemetery in 1869 — 51 years later. There was some uncertainty about that identification, too, until remains were discovered with one leg. Several years after his death, Virginia granted his estate $30,000 in old military payments and continued them until 1913.

MERIWETHER LEWIS AND WILLIAM CLARK

Lewis and Clark are two names united in a broad stroke of American history whose eventual forgotten fates included success and suicide.

Lewis was born in Virginia in 1774. He had no formal education until 13, enjoyed the outdoors and hunting and once tutoring began developed a strong interest in natural history. He later joined the Virginia Militia, then the U.S. Army — where among his commanders and eventual good friend was one William Clark. In 1801, President Thomas Jefferson appointed Lewis, who had grown up a neighbor, as his personal secretary allowing him to live in the presidential mansion where he had frequent contact with Jefferson and other distinguished guests.

Jefferson encouraged Lewis to take classes in astronomy, botany, zoology and medicine. As the Pacific expedition was planned and Jefferson told Lewis of the various commercial, scientific and commercial reasons for the trip, Lewis invited William Clark to join him.

William was the ninth of the 10 Clark children. He also was tutored at home. Once the Revolutionary War was over — and five Clark brothers fought in it — the family made its way by flatboat down the Ohio River to Mulberry Hill in Louisville in 1785. In 1790, William Clark was commissioned a captain in the Indiana Militia, fought in several battles, but resigned in 1796 at age 26 to live at Mulberry Hill. In 1803, Lewis recruited him for the Corps of Discovery.

“When you think about it,” said the Filson’ s Holmberg of the forgotten reach of the Clark brothers, “George Rogers Clark played an important role in getting the old Northwest Territory for the U.S., which doubled the size of the United States and here comes little brother William who with his partner explores the Louisiana Purchase, which doubled the size of the U.S. at that time. That’s a pretty darn good claim.”

The meeting of Meriwether Lewis and William Clark is commemorated with a statue at the Falls of the Ohio State Park. A total of 33 volunteers would join the party that moved up the Missouri River in May 1804. Along with the party was York, William Clark’s slave since childhood, who would play a vital role in the success of the mission.

The epic journey to the Pacific Ocean lasted three years and covered about 8,000 miles. Every manner of guile, courage, intelligence, luck and survival skills were needed, along with being able to negotiate with about 20 separate Native American tribes, many of whom had never seen a white man. Lewis and Clark brought back with them a bounty of maps, journals, botanical and geographical information. The two men became national heroes as the rest of their party disappeared back into history.

Clark had a mostly good life after the expedition, living most of that time in St. Louis. President Jefferson appointed him brigadier general in the Louisiana Territory and U.S. agent for Indian Affairs, a skill he had developed on the expedition. He had a reputation as a harsh owner of slaves but treated the Native Americans more fairly, but also allowed their forced removal from their homelands. He lived to 68 and was buried in St. Louis.

“He’s chief Indian agent for the West. He becomes territorial governor of the Missouri Territory,” said Holmberg.” He lives a very prominent post-expedition life.”

Not the same for Meriwether Lewis. He moved to St. Louis as Jefferson appointed him governor of Louisiana Territory and he received a 1,600-acre land grant. He also agreed, at Jefferson’s insistent request, to publish the full Corps of Discovery journals. As Holmberg explained, Lewis was not a politician and was criticized by political rivals and co-workers who complained he was too military and ultimately ineffective.

“He was trying to merge the French population and the Americans that are pouring into the territory and the land issues,” said Holmberg, “and he gets into land speculation and runs afoul of the government just like George Rogers Clark.” There was also speculation, said Holmberg, that Lewis also had a drinking problem, was probably taking laudanum, was suicidal and may have been bipolar.

In August 1809, Lewis, deeply in debt and dealing with a nervous breakdown, decided to go back to Washington to try to save his job, reputation and finally — after a lot of pressure from Jefferson — get the journals written. Taking the Natchez Trace through Tennessee back to Washington, Lewis stopped at an inn called Grinder’s Stand on Oct. 10, 1809. The innkeeper’s wife, Priscilla Grinder, would say she heard gunshots that night and found Lewis in the morning badly wounded with gunshot wounds to the head and stomach along with self-inflicted razor slashes on his body. He died in his own blood at age 35. Years later came the inevitable speculation he had been murdered, but no proof was found.

Lewis was buried at Grinder’s Stand in an unmarked grave that a year later was marked with a wooden fence. In 1848 the State of Tennessee erected a monument over the site, but all became overgrown and abandoned until 1905. It was 1925 before the death site was made a national monument. In 2009 — the bicentennial anniversary of the Corps of Discovery — the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation honored him with 2,500 people in attendance.

YORK

William Clark’s slave, York, was born in Virginia in 1770 and left to Clark in his father’s will. York, the same age as Clark, became his constant companion when he lived in Louisville and then on the Corps of Discovery. Historian Stephen Ambrose, whose book, “Undaunted Courage,” forever illuminated that journey, said York was a big man, strong and athletic. York would become a great help on the expedition because he was such a curiosity; many Native Americans had never seen a Black man before; he provided instant rapport, connection and created a sense of trust.

At least for that journey, York was a full and popular member of the expedition. He had his own rifle. He got to vote on community decisions. He went on scouting trips and participated in trades with the Native Americans.

“He could hunt, he could fish, he could handle boats and he could swim,” said Holmberg. “We know that because Clark in his journals talks about York swimming out into the Missouri to gather greens for his supper. He could do everything the other guys could do and as a servant he could make camp life easier for Lewis and Clark.”

Yet York’s personal life before and after the expedition always spoke of a slave-master relationship. When William Clark moved to St. Louis from Louisville, York had to leave his wife behind and he complained to Clark about it

“York speaks up,” said Holmberg. “It’s like ‘well hire me to somebody here in Louisville so I can stay here with my wife. Sell me to somebody here in Louisville so I can stay.’”

York had to move to St. Louis with Clark. When York returned from the Lewis and Clark expedition and all other party members were rewarded with land grants, York received nothing. Given the work he had done on the journey, York expected to be freed from slavery afterward. Clark, with a reputation of being coldhearted with his slaves, wouldn’t grant it.

In the fall of 1808, Clark did allow York to briefly return to Louisville but ordered him back in St. Louis in 1809, and he was very unhappy about it. Holmberg said Clark beat York after his return and had him jailed after stories — true or not — surfaced that York had been drinking in taverns and telling expedition tales.

A letter at the Filson Society indicates Clark remained unhappy with York and sent him to Wheeling, West Virginia, with a load of trade goods. Clark then wrote a letter to his brother, Jonathan, in Louisville saying that when York got to Louisville on the way back from West Virginia to sell him or hire him out to a severe master.

York was hired out to a severe master. Still a slave to Clark, he opened a freight-hauling business in Louisville. Freedom was just across the river in Indiana but York, trapped as a slave in body and mind, remained in Kentucky, perhaps still wanting to reunite with his wife whose master had moved somewhere south.

Clark would say he finally freed York about 1817. York moved to Nashville, Tennessee and started a freight business there, possibly still seeking his wife. History remains vague here. One story is that York died somewhere in Tennessee and was buried in an unknown grave. Another — more apocryphal –— is that he returned West and lived free as an honorary chief among the Crow Native Americans.

York, at least, found honor in the end. He has since been memorialized in plays, several books, an opera and a statue by Louisville Sculptor Ed Hamilton on the Louisville waterfront. A short distance away, a witness to much of this, the Ohio River continues its relentless journey downstream through time and history and even presidential elections.