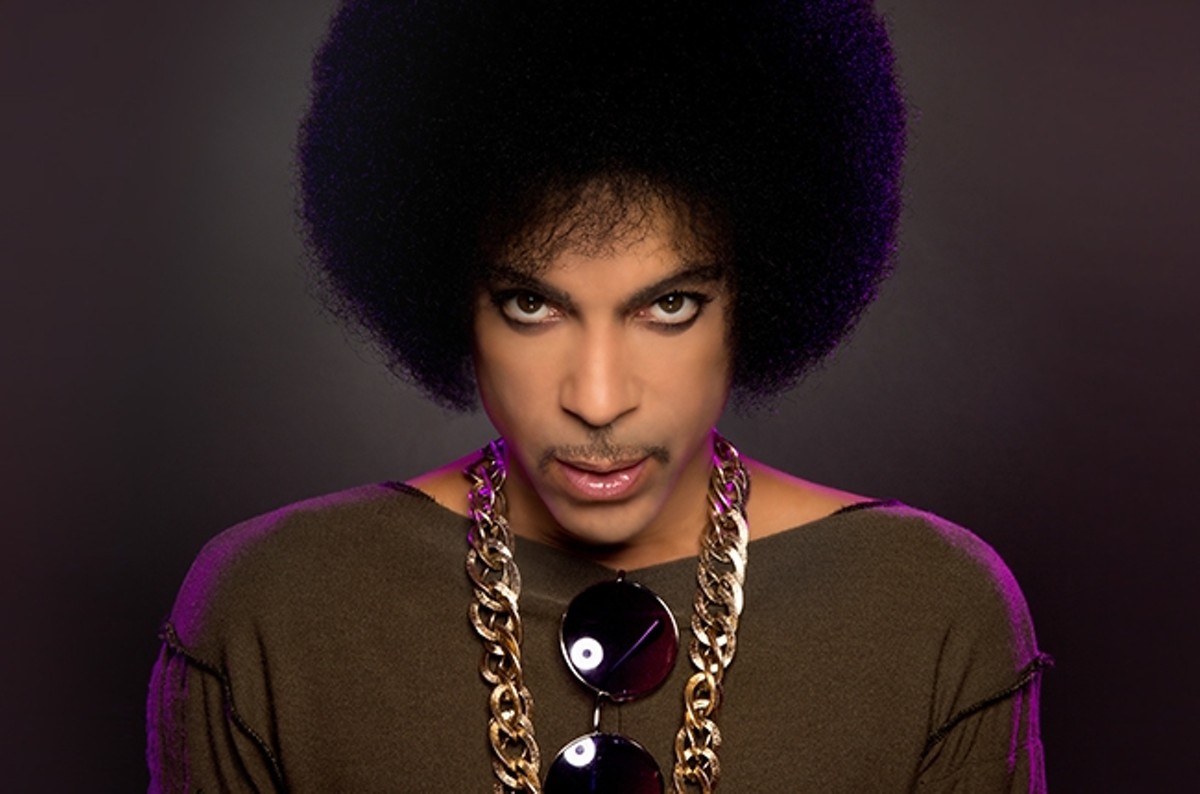

The first time I saw Prince, his albums were nestled in a stack of records at my cousin’s place. On one, it was a midrange shot of him, bare-chested against a blue background with his hair blown straight and feathered away from his face. On the other, he was wearing a trench coat, a scarf and underwear. I was very young, but I understood that something about him was dangerous. Perhaps he was something that I shouldn’t know. When 1999 was released, I was 9. My neighbor had the record, and almost every day, it seemed, I would go over to his apartment and play with his kids while we listened to 1999 on repeat. It was the soundtrack to the onset of my pubescent years. Those years weren’t graceful. I didn’t bloom easily. I was a rough kid, playing football with boys and buried in the middle of a book much of the time. I knew that my body was changing and I was beginning to feel things that I hadn’t before. Some of these sensations were wonderful. Others were painful and overly emotional. It was music that guided me through.

Hearing that Prince had died, my years of awkward wonder and titillation came to a final stop. I cried. I’d lost a piece of my childhood and also a piece of my mythology as an artist. No one creates alone. Not really. Most of us who write, paint and make music, etc., are amalgams of our influences. Prince was one of mine. His death felt personal, as if a relative had died. I had the urge to call my own family to tell them the news, as if they’d be able to help me process and plan for what’s next. Prince wasn’t family, but he was. He was a brother in art. I mourn him now because of art.

I’ve always been moved by things that are strange or beautiful: It is a bonus if that thing is both strange and beautiful as Prince was. He was ethereal and impossible, and, at the same time, his upper Midwestern upbringing betrayed him. He was tethered by his roots, just enough to keep him real when his mystique seemed to try and swallow him up. As his death brought revelations about the man, I learned that a donation he made helped save the Western Branch library here in Louisville. This library was the first branch of a public library system exclusively for African Americans. This was my library as a child. I lived within blocks of the place and spent many afternoons there engaged in reading programs or restocking my supply of books for the month. Knowing that Prince had stepped in to save this place that is important to African American history, and my own history, reaffirmed why it isn’t just his music that makes him worthy of our grief. He touched the world and, very specifically, many places where being young and Black felt safe. At the same time, he made sure to touch the places where young Black people were not safe. He spent his money and time to leave a better world.

When he came to Louisville last year, I was lazy about getting a ticket. I figured he’d been here a few times, he probably wouldn’t play many songs that I knew and likely he’d come back. After all, the drummer was from Louisville. The night of the final show, a few tickets went on sale at the box office. A friend managed to secure three tickets, and I didn’t hesitate.

When he took the stage, I remembered all the times Prince had been right where I needed him, in his songs and his movies. Finally, he was right in front of me and, overwhelmed with emotion, I was moved to tears. It was a private kind of cry — a few tears quickly wiped away without anyone knowing. Very different from the tears that fell when I learned he’d passed on.

Those tears were grief, but more than sadness, I felt gratitude. I feel blessed to have lived in a world where Prince existed: The same world that gave us David Bowie, Michael Jackson and Jeff Buckley. I was moved because I was able to bear witness to the beauty he gave the world. It was a beauty more perfect than the rose, more expansive and less tangible. It was cosmic. It was this that finally broke the tethers of his mortality. How very lucky we have been.

![[Vlog] The Metal Grind With Athena Prychodko (4/30)](https://media1.leoweekly.com/leoweekly/imager/vlog-the-metal-grind-with-athena-prychodko-4-30/u/golden-s/16271931/image-1.jpg?cb=1714449156)