Louisville has many historic architectural attractions, including Old Louisville, City Hall, St. James Court, Whiskey Row, Farmington, and Locust Grove. For buildings of the modern era, however, Louisville has not been known as an architectural draw. Sure, there’s the Kentucky Center for the Arts, designed by the Caudill Rowlett Scott firm; Mies van der Rohe’s American Life Building; and the Muhammad Ali Center, designed by SKOLNIK Architecture. As well, the Omni Hotel adds an interesting twist to the skyline. But most of downtown, from older to newer, is pretty much standard-issue design from the respective periods.

Once upon a time, that was all to change. That change was to be called Museum Plaza.

How much of a change? The concept and subsequent design was right out of "Star Trek." As Nico Saieh told ArchDaily in 2009, “Museum Plaza is — in my opinion — one of the most amazing mixed-use projects of our time. It makes all the variables fit together on pure volume — with a Miesian look.”

Proposed by Laura Lee Brown and Steve Wilson, of 21c Museum Hotel note, along with Steve Poe and now-Mayor Craig Greenberg, Museum Plaza was to be a 62-story mixed-use tower. Within the tower would have been luxury and studio condos, office space, a Westin Hotel, a public plaza, restaurants and shops, a space for contemporary art, and studio space for the University of Louisville’s fine arts program. Calling the building a tower, though, needs some further definition.

In his book "From Bauhaus to Our House," Tom Wolfe, not much of a fan of the International Style, calls those towers BFBs (Big F’ing Boxes). Case in point locally: the PNC Tower. True, Museum Plaza would have towered, but as a collection of adjoining towers sitting on a plinth eighteen stories up, known as "the Island." When viewing the digital renderings of Museum Plaza, the wooden-block game Jenga comes to mind. The design would have been radical in any city — New York, Los Angeles, London, Berlin, Tokyo, Beijing, Singapore. Here in the Gateway to the South, on a one to ten out-there scale, Museum Plaza was a fifteen.

Erecting a fifteen at the corner of Seventh and Washington Streets meant a clash between the architecture and scale of the West Main Street District. A clash? Actually, a rip — not between then and now, but between way back then and the future. Feathers were ruffled, of course, including those of preservationists. Then-Mayor Jerry Abramson was concerned the building would always remain separate from the immediate environs. But then, that was the point.

Looking north to the Ohio River, Museum Plaza would have loomed as the invitation it was to that future. At night, the lit floors would have loomed even more intensely. Sitting near the south bank of the Ohio, it might have been Louisville’s version of the Gateway Arch in St. Louis.

Of all that sets Homo sapiens apart from the rest of biological creation, perhaps ideas head that list. The word "idea" is derived from the Greek "idien," meaning "to see" — as in, to see a connection, to see the future, to see a possibility. We all get ideas. Most evaporate soon enough. Heck, we’d go crazy if they didn’t. Others persist for a while, and some of those others persist on. Persistent ideas still remain just ideas unless they are eventually dragged into existence, as Eero Saarinen’s Gateway Arch was. Brown, Wilson, Poe, and Greenberg did their best to drag Museum Plaza into physical reality, but could not. Idea-dragging does, in fact, require the alignment of events and people and places, as well as an unbroken series of yeses, however jagged that continuity. In the end, that alignment just did not happen.

The primary purpose of the 21c Museum Hotel is to allow culture to be immediately accessible, beginning with the huge golden statue of David on the southwest corner of Main and Seventh Streets, then continuing in the lobby and throughout the hotel. The same accessibility would be the heart of Museum Plaza. The project began when Joshua Ramus and the REX Architecture firm were approached by the Museum Plaza core team of Brown, Wilson, Poe, and Greenberg.

The team’s vision "was really a beautiful ambition,” Ramus recalls. They told him, “We want to create a contemporary art institute. Is there an economic scenario where we could create a for-profit development in which we will also build the art institute, the net profit of which will then be turned back into the endowment for the art institute?”

The core team had asked their question of just the right person. Ramus has an international reputation as an architect who sees both the possibilities and limitations of a site, with the further ability to design a building far beyond the mundane. As local architect Mose Putney notes, “The solutions to the building program were profoundly inventive and architecturally/structurally brilliant, no doubt honed to surgical exactitudes within Atelier Rem Koolhaus.”

Ramus came to Louisville, or, rather, stopped over on his way to Dallas, as a favor to a friend who was dating Matthew Barzun’s sister. Barzun is married to Brooke Brown. After landing here, Ramus was taken to a rather abandoned land parcel, which the core group saw as the site of this art institute and whatever would support it. The favor, now performed, turned quickly into Ramus’ very active and direct involvement with the project. “We’re standing on the top of a parking structure overlooking the site when Steve Wilson asked, ‘Are you ready to present?’ And I said, Am I what? In the ten minutes walking from there and then going up to their office, I had to scrap together a presentation [about] who we were and how we thought.” Soon after arriving in Dallas, Ramus received a phone call, the purpose of which was to ask if he’d like to be architect of the project.

“We went on a worldwide study tour to look at contemporary art institutes, contemporary art institutes that were mixed with other programs, developments that had used cultural programs within the mix. In that tour, we got to know them and start[ed] to understand how sincere this desire was.”

He continued, “It [the process with the core team] was just very direct. No games. They said what they wanted, what the aspiration was. Whatever I presented appealed to them, and we embarked on this kind of crazy, beautiful, ambitious thing. It was super refreshing. Zero cynicism, just total optimism.”

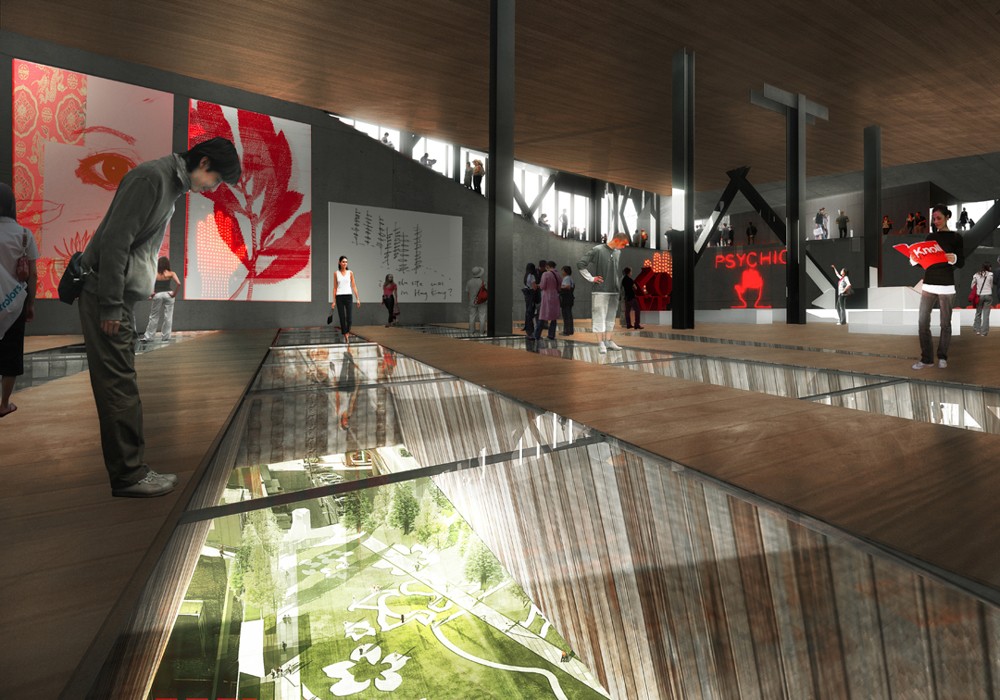

Ramus’ plan was to allow the areas of the public space, the Island, to flow one into another. Such public spaces in typical towers are at street level. When they include a gallery, that space often comes off as an afterthought, one with a predictable experience regarding layout. Because of the Museum Tower site, which was situated between a flood wall and I-64, such street access was not possible. As such, the Island defined itself in the middle of the overall tower. A dot matrix system in the gallery walls within the Island would have, depending on need, made them opaque or transparent. In addition, glass ceiling and floor areas in the gallery would have allowed views of the tower complex, up and down. The gallery itself, then, would have been an interactive work of art.

At first, the core team was doubtful about the lack of boundaries. To quote a 2008 Esquire profile of Ramus, "How America's Smartest New Architect Saved Louisville":

“In a meeting with the client in Louisville, they said, ‘Wait — so what you’re saying is, a kid in a bathing suit will come down from the luxury condo and have to walk through the public space to get to the swimming pool next to people in black-tie going to see the opening of the de Kooning show?’ And we’re like, Yesssss! Isn’t that exciting?”

That parallax shift, Ramus notes, is, “often the role of the architect. I think a lot of architects can be patronizing and sort of tell the client what they should do. I actually think the role of a good architect is to be more like a mirror, and say do you realize this is what you’re already doing, and then to turn up the volume and say this is how we can do that even more.”

The core team soon appreciated the juxtaposition of Ramus’ Esquire quote. As Ramus explained, “If you look at how 21c operates, that’s at its core — this idea that culture is immediately accessible, and should be involved in people’s everyday life. To be honest, I don’t think we were saying something radical to them; I think we were just making it apparent that that’s what they were already doing. They were shocked at first, and then realized, 'That is what we’re doing. That is our mission. We want the best art in the world in downtown Louisville.'”

Ramus demonstrated that the mixed-use aspect of Museum Plaza had six distinct elements: the condos, office space, a hotel, a public plaza, restaurants and shops, and the art and studio space. In an illustration, he took six separate towers west of the center of downtown, cut the imagined site in half, then swung the eastern half under the western half, elevating that western half, all the while maintaining the six separate structures in the unified design. Between the top three and the bottom two structures was the plaza, that complete redefinition of public space. In addition, a structure at about a 30º slant would have provided street-level access by a funicular, a sort of counterbalanced tram. This approach not only resulted in an astonishing building, but it also redefined the traditional placement of public space, office space, and residential space, allowing the towers to remain structurally distinct. Such astonishment would have redefined the downtown area, and the city itself.

In 2006, a formal announcement was made for the Museum Plaza project, an announcement conveying the intention to erect a building that could have been on the Starfleet Academy campus circa 2161. On October 25, 2007, a groundbreaking ceremony was held, but the bringing of the 22nd century in the 21st was not to be.

As mentioned, projects on the scale of Museum Plaza — from the Eiffel Tower to the Saturn V rocket to the first COVID vaccine — require an alignment. Maybe not of the stars, but definitely of people and money, and of that string of yeses. When researching almost any ambitious, long-term project, of any sort, such an alignment — that is, serendipity — enters the equation.

For Museum Plaza, serendipity was present at the beginning, specifically regarding financing, as well as resolving raised conflicts of interest concerning hotel room tax distribution — and, of course, in the initial collective vision of Brown, Wilson, Poe, and Greenberg, and then of Ramus. However, by the next January after groundbreaking, that serendipity began fading quickly. Construction had halted due to vibrations caused by excavating equipment, which threatened the structural integrity of the nearby nineteenth-century buildings.

More significant, though, was the unfortunate timing. By that New Year’s Day, a massive worldwide financial downturn was already underway, to last more than one and a half years. Despite a likely $100 million HUD loan, filed for in the summer of 2010, Museum Plaza was history by the following summer. In August 2011, developers announced that the project had been abandoned. Today, part of the parcel of land has, of all things, pickleball courts.

Over the last ten years, other projects for the land have been proposed, obviously without success. Whatever project might be built will not have the vision and the utter electric creativity that was once Museum Plaza. How electric? Quoting Putney again, “Towers are geographic wayfinders, city-core magnets, icons that etch place identity into memory. Approaching Louisville’s already modest [...] skyline from any of the cardinal directions doesn’t present much evidence of imaginative architectural invention. Museum Plaza would have radically changed that, which, to my way of thinking, could have been pivotal in elevating the Spirit of Louisville both internally and externally, physically and temporally illustrative of what we’re capable.”

He added, "Museum Plaza certainly was an ambitious undertaking. I celebrate the Museum Plaza teams’ cunning efforts to go as far as they did and create such a spectacular proposal.”

What might have been is far too often a human foible. Yet just as often — or sometimes, anyway — the wondering is an all but irresistible trinket, an itch from the past that still needs scratching. Imagine, then, coming across or along the Ohio in passing through our town, or to arrive, only to spy this letter from the future, reaching skyward in a way no other local building can — indeed, as most buildings anywhere across the globe cannot.

And so, perhaps the key word at hand is "juxtaposition." Juxtaposition, especially in the modern realm, is often key to a meaningful work of art. As that fifteen on the out-there scale, Museum Plaza would have been utterly juxtaposed. Not only as a physical presence within its surroundings, both immediate and beyond, but in the minds of those afar from Louisville who think of our city only on the first Saturday in any given May.