In the summer of 1985, Robert and Martha Marshall were moving from their West End apartment into a new home. They wanted what a lot of people do: A house big enough for their family with a yard for their kids to play in — and at a price they could afford. They found that on an all-white block of the Sylvania subdivision out near Pleasure Ridge Park. But any hope for tranquility was shattered when Martha noticed her 11-year-old son’s bedroom was on fire early one morning. Martha was up late — uneasy in the new home after men driving by in a pickup truck shouted the n-word two days before — and was able to get her son and 13-year-old daughter to safety quickly. The fire destroyed one bedroom and caused smoke damage to the rest of the brick house. Robert was staying at the family’s rental on Algonquin Parkway with their 9-year-old daughter at the time of the fire. When he returned to their fire-damaged new home, he found a “Join the Klan” sign and a swastika on trees outside.

“I never thought that something like this could happen in 1985,” he told the Courier Journal after the blaze.

The Marshalls’ search for answers and justice would ultimately yield convictions, with two men arrested within 10 days of the attack ultimately pleading guilty.

Their search would also set in motion a series of events that would lead to the uncovering of a Ku Klux Klan faction active in the ‘70s and ‘80s — the Confederate Officers Patriotic Squad — that was led and dominated by Louisville area police officers. Among the group’s members was a man who was chief of the now defunct Plantation Police Department for three years in the early 1980s.

The ripples are still being felt: Just last month, reporting by the Courier Journal revealed that two officers with the Jefferson County Sheriff’s Office had been formerly associated with the Klan faction. Those two officers, Gary Fischer and Mike Loran, have since left the department.

But the history of the Klan faction has largely been forgotten. Wading through Courier Journal archives from the 1960s-1990s and speaking to experts, in recent weeks LEO Weekly has pieced together a history of local law enforcement officers who were in the Klan.

The Backstory

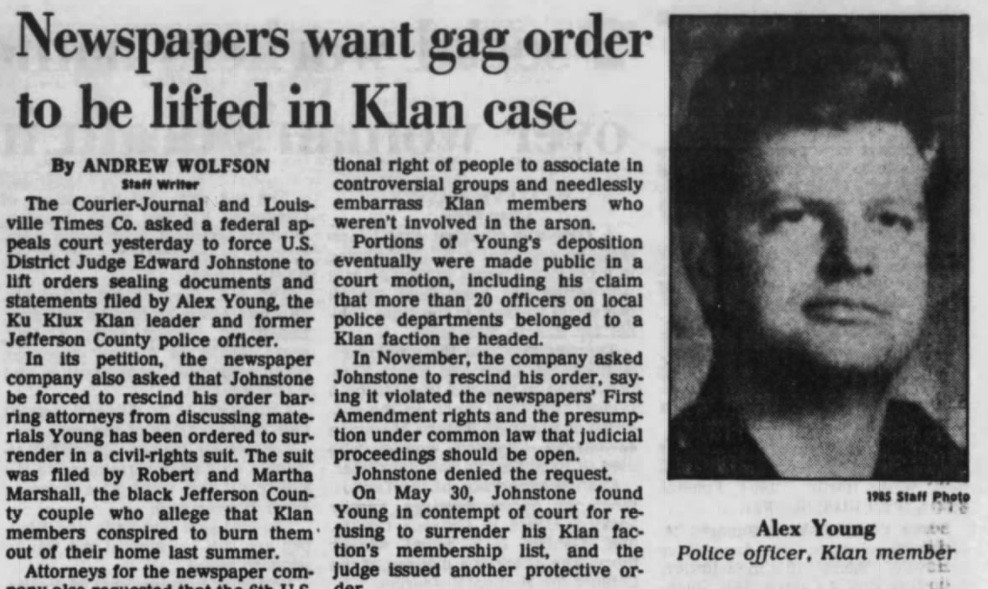

More than three weeks after the firebombing of the Marshalls’ home, Jefferson County Police Chief Russell McDaniel said he received a call accusing a 36-year-old officer named Alex Young of being a Klansman. After being questioned, Young, who worked in the department’s helicopter unit, admitted he was in the Klan and police said he agreed to leave the white supremacist organization.Young was quickly transferred from the helicopter unit to the department’s property room — a move the department denied was punitive — but no other action was taken.

Like the last time there was news about Klansmen on the force nine years before, the department said they had a chat with the concerned parties and resolved the issue — case closed, no problem.

Two 20-year-old white men, Carl Ray Bramer, and Billy Wayne Emmones, as well as an unnamed juvenile, had already been arrested and charged with the attack on the Marshalls’ home by the time Young was spoken to. Bramer was charged with first-degree arson and told police that he had used gasoline and a cigarette lighter to set the Rutledge Lane home on fire. Emmones was charged with complicity.

While they initially pleaded not guilty, they would go on to plead guilty in 1986. Bramer was sentenced to 30 years in prison while Emmones, who pleaded guilty but mentally ill, received a suspended five-year sentence and five-year probation.

After the arrests, the Jefferson County Police said that Klan was not involved and had actually assisted them in their investigation; A local Klan leader, Jim Kennedy, denied that, saying, “the Klan would never turn in a white man for any racial attack.”

A little more than two weeks after the firebombing, more than 80 people gathered a few doors down from the Marshalls’ residence for a fundraising drive for the two jailed men. There were shouts of “keep them out” and “this is the American way.” More signs encouraging people to join the Klan were hanging on fences and posts in the area.

Kennedy, the local Klan leader, was there and decried the suspects’ bail amounts, set at $20,000 for Bramer and $5,000 for Emmones.

“I’m saying this is racism against whites,” he said.

According to the CJ, one 20-year-old resident at the rally said that the Marshalls “had their equal rights to stay in the West End. We want our equal rights to keep them out of Sylvania.”

At the end of the paper’s story about the fundraiser, the address of P.O. Box for donations to the defense fund was listed.

In the immediate aftermath of the attack, some Sylvania residents had told the CJ that earlier attempts by Black people to move into the area had been met with cross burnings and firebombings, driving them away. (“These kinds of incidents were not unheard of, but they weren’t always investigated. They didn’t always come to light like this,” said Catherine Fosl, a professor of women’s, gender and sexuality studies at UofL who was the biographer of the late Louisville civil rights activist Anne Braden).

The firebombing of the Marshalls’ home quickly resurfaced memories of another Black couple, the Wades, whose Shively home — which was under 24-hour police guard — had been dynamited nearly 31 years to the day before the Sylvania attack. The state had said there were two theories behind the bombing: That it was meant to get the Wades out of a white neighborhood or that it was a communist plot meant to “stir up trouble” between the races. With the United States in the grips of the Red Scare, civil rights activists Carl and Anne Braden, who were white and bought the home for the Wades to circumvent housing segregation, were charged with sedition along with five others. Painted as a communist, Carl Braden was convicted on sedition and would ultimately serve seven months in prison.

Three decades later that kind of violence was still occurring.

In the pre-dawn hours of Aug. 24, 1985 — less than two months after the firebombing — the Marshalls’ now-empty home was set on fire again, destroying it.

The next night, the Klan held a rally in Sylvania two blocks away, telling those gathered that Black people needed to stay out of white neighborhoods like the one they were in.

As in the first firebombing, the KKK denied responsibility.

“Every time something like this happens, it’s the KKK. We get the blame for it. I have no idea who possibly could have done this,” Kennedy, the local Klan leader, told the CJ.

No arrests were made in the second arson attack.

The Lawsuit That Dug Deeper

Just before their home was set alight for a second time, the Marshalls had filed a suit in federal court against Bramer, Emmones, the minor and “unknown defendants” who were members of the KKK.As part of that suit, the Marshalls’ lawyer, Morris Dees (who was also chief trial lawyer for the Southern Poverty Law Center) sought to force Young to turn over Klan membership lists after Southern Poverty Law Center investigators found that the officer had rented a post office box used as a mailing address for the Klan and a “Confederate Officers” group believed to be made up of local police.

The suit saw Young and other officers subpoenaed and kicked off a two-year-long legal battle to get Young to turn over a list of officers involved in his group. The Mashalls and their lawyers never accused Young of involvement in the firebombing. Rather, they suspected potential Klan involvement and believed that a list of Klan members could help lead them to perpetrators.

Testifying under oath in November 1985, Young outlined details about the Confederate Officers Patriotic Squad, or C.O.P.S., the Klan faction that he led, which he said had about 40 members — more than half of them law enforcement officers. Besides the Jefferson County Police Department, Young said that officers from the Louisville, Jeffersontown, Rolling Hills, Prospect and Plantation police departments were part of his organization. But according to the CJ, no names of officers in the Klan were included in the court documents relating to Young’s deposition.

In that deposition, Young also said he “probably” used an FBI computer to see if Klan members were wanted by the police or not and that he knew of the August Klan rally in Sylvania a week beforehand but did not inform superiors. He considered it “common knowledge” on the force that he was in the Klan and claimed he was one of the top 10 Klan members in the entire country.

Days after news of C.O.P.S. broke, Young was fired from the Jefferson County Police Department for lying about quitting the Klan and distributing more than 10,000 pieces of “extremely disrespectful, discriminatory and derogatory hate literature.”

After Young was fired, the Jefferson County Fraternal Order of Police Lodge 14 gave a vote of confidence for members to belong to any organization they wish so long as it does not interfere with their job as a police officer.

While the unveiling of C.O.P.S. was big news in Louisville, it was not the first time there had been signs of police involvement in the Klan.

In January 1968, the leader of the Kentucky Ku Klux Klan, Grand Dragon Boyd Smallwood, told the Courier-Journal that there were three Louisville police officers and one county police officer in his organization, including one who was a “high ranking” official in the Klan. He added that he would relinquish control of the Klan if there was a police official that wanted to take it over.

“Policemen generally are good loyal Americans that you can depend on,” he explained to the paper.

Smallwood described police as “stable and effective” Klan members and said efforts were underway to recruit more of them. At the time, Jefferson County’s police chief said they had “never heard a whisper” about Klan activity on the force.

In June of that year, after quitting the Klan, Smallwood would tell the paper that the four officers he had previously mentioned had also left the group.

Then, in 1976, the FBI warned the county and city police departments of Klan members within their ranks. According to a 1977 story in the Courier Journal, an FBI report the previous year found that 13 city and county police officers were members of the Klan. Informants also told the feds that one county officer was trying to organize a law enforcement-only Klan branch in the area.

At the time, the Jefferson County police chief, McDaniel, said he had discovered two officers who were Klan members. He would not make their names public, but said they had decided to leave the KKK and that neither were working in areas with large Black populations.

Louisville’s police chief at the time, John Nevin, said the FBI did not identify specific officers in the Klan and that there was nothing departments could do anyways as being in the Klan was not against department regulations.

Three years before the firebombing of the Marshalls’ home, a Klan rally in the gymnasium of Valley High School on Dixie Highway attracted an “enthusiastic crowd” of 800.

Louisville’s experience with police officers involved with extremism during that era was not unique.

In the city of Richmond, California, just north of Oakland, a group of officers called “the cowboys” were unveiled during a civil trial over the deaths of two Black men at the hands of police. In 1983, the city was ordered to pay $3 million in damages to the families of the men after Richmond citizens and fellow police officers testified about how the group habitually targeted Black people with harassment and discrimination.

And in the 1990s, a federal judge would call a group of Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department deputies, the Vikings, a “neo-Nazi, white supremacist gang.”

“That ridiculous narrative that white supremacism or racism is particular to the south, well, that’s total bullshit. It’s everywhere,” said Louisville-based activist Hilary Moore, co-author of “No Fascist USA!: The John Brown Anti-Klan Committee and Lessons for Today’s Movements,” which looks at anti-Klan efforts in the 1980s.

Not long after Young was fired, more details about C.O.P.S. started to flood out.

In December 1985, just weeks after news of the C.O.P.S. faction was publicly revealed, the former police chief of the small home rule-class city of Plantation in eastern Jefferson County told the Courier Journal that he had been a member of the Klan group. The former chief, Roy Shaffer Jr., said the group’s purpose was to push back against “reverse-discrimination” and maintained that the group was not violent.

“We were sworn to uphold the law. We wouldn’t tolerate people who would break the law,” he told the paper.

Shaffer’s gun shop — also called C.O.P.S. — had for a moment been at the center of investigations into local Klan activity due to its name, but he said the name was purely coincidental.

In January of 1986, the release of depositions of other officers shed more light on the group.

One Louisville police officer, Robert Snyder, would say he joined Young’s group because of its stance against communists, but did not initially realize it was a KKK faction. He said he quit because of the group’s racial and religious discrimination. Another Louisville officer, George Fertig III, said frustrations with affirmative action drove him to join the group. In a December 1985 deposition, Fertig said he did not see any conflict between being in the Klan and being a police officer.

“I’ve never felt it was a conflict whatsoever,” he said, according to the CJ. “I’ve always been a professional police officer… and it’s never interfered with any of my duties.”

Jefferson County patrolman James Dunlap Jr. would say C.O.P.S.’s role was to “write to politicians to keep white rights as well as Black rights.”

In the depositions, Snyder, Fertig and Dunlap said they had donated money to Young’s legal fund, but denied any recent involvement in C.O.P.S. An Anchorage officer told the CJ he believed he was subpoenaed because he had won a country ham at a raffle to raise money for Young’s defense.

Gary Fischer, who left the Jefferson County Sheriff’s Office last month after his membership in the Klan resurfaced, said in a December 1985 deposition that he joined the group thinking it was “more or less a social organization.” In his deposition, Fischer also denied any recent involvement with C.O.P.S., saying that after he was initiated into the group, he no longer participated in their activities and did not consider himself a Klan member. Fischer also served as vice president of the River City FOP Lodge 614, stepping down in 2004. The FOP Deputy Sheriff’s Lodge 25 website currently lists him as the group’s sergeant at arms.)

In transcripts of a November 1985 interview between Young and Jefferson County Police Department investigators obtained by the Courier Journal in early 1986. Young said that he joined the Klan because “I get kinda bored with just the average routine life… I think white people should have an organization they can go to without fear of gettin’ transferred.”

He denied that he was anti-Black and said that he instead “bent over backwards” to treat Black people fairly knowing that one day he might be exposed as a Klan member. He characterized the Klan as “not anti-Black…it’s very pro-white.”

Young did not feel that being in the Klan impacted his job as a police officer, saying “I always liked being a police officer…I just happen to like being a party of a right-wing movement, too.”

In that interview, Young also claimed that C.O.P.S. was a name that he had made up and that he was the group’s only member.

Lasting Legacy

Carla Wallace, the co-founder of Showing Up for Racial Justice who was an activist with the Kentucky Alliance Against Racist and Political Repression at the time that C.O.P.S. was unveiled, saw hypocrisy in how officers said they could balance the Klan with their job.“You cannot take an oath to the Klan and an oath to serve the public and carry a gun,” she said in an interview with LEO. “Those two things contradict each other, because the oath you take to the Klan is totally counter to serving the public equally and targets Black people, Jewish people, LGBT people.”

While C.O.P.S. members who became known to the public downplayed the group — likening it to a social club and saying it was about lobbying politicians and voicing frustrations — the literature handed out by Young were a nod to its extremism.

According to the CJ, one pamphlet distributed by Young showed the face of a Black man with the words “HE MAY BE YOUR EQUAL, BUT HE SURE ISN’T OURS.” Another depicted a white barber decapitating a Black customer.

Asked about the hate literature he had distributed in the November 1985 interview with police investigators Young said, “It’s, just, uh, something you’ll find, like, on Polacks [a derogatory term for people of Polish descent] that you’ve seen passed around the police department.”

And after C.O.P.S. entered the public eye and Young found himself embroiled in legal battles, court records would show that Young placed phone calls to what the Southern Poverty Law Center attorney who was representing the Marshalls called “the most militant neo-Nazi and Klan leaders in the U.S.” Two of the leaders contacted by the paper said Young had asked them for financial or legal assistance.

In December 1987, Young would finally agree to turn over a roster of Klan members to the Marshalls’ attorneys after more than two years of court battles. However, it was ordered that the list be sealed and only open to parties in the case.

Young attempted to sue the Jefferson County Police Department for millions of dollars in damages over his firing and, later, the Louisville Police Department for not hiring him.

In 1992, it was revealed that former county police spokesperson Bob Yates, who had previously commented to the press about issues that potentially involved the Klan over the years, had appeared in a photo wearing the robe of the white supremacist group. He denied he was in the KKK and said he put them on as a joke at a Christmas party at C.O.P.S. Klan leader Alex Young’s house more than a decade earlier. But he said he suspected Young was in the Klan given the decorations in his home — including a picture of a burning crosses above the bar. He said he went to Young’s house because Young threw good parties.

The photo had allegedly been purchased from Young by the owner of a cemetery who thought they might be able to use it as leverage against the police department, but that’s a story for another day.

A year later, in 1993, another former Jefferson County police officer, John Bersot, testified that he had been in the Klan when he was with the force in the 1970s, saying he joined over issues like affirmative action and busing. Back in the 1980s, he had been questioned in connection to the Marshalls’ probe into police officers on the Klan. At the time, he told the press he had never been in the Klan.

When Louisville Metro Council President David James heard the news about the former Klan members still working for the Sheriff’s Office, he was not surprised.

A former police officer, James was hired by the Louisville Police Department in 1984 as the force was under federal orders to hire one Black officer for every two white recruits until the department met a diversity goal. On his first day on the job, he found a note on his locker calling him the n-word and telling him to quit. Two years later, a white officer would call him and another Black officer that same slur in the parking lot of the old FOP lodge on West Breckenridge Street.

“He felt very comfortable calling me the n-word in front of his friends; He didn’t feel so comfortable after I hit him in the mouth,” James said. For white officers on the force, that kind of behavior “was not unheard of back then… it was okay.”

James said he didn’t know of fellow officers who were in the KKK back then, but there were rumors about some as well as colleagues he knew didn’t like him because he was Black. When the news about the C.O.P.S. faction broke in 1985, some officers went out of their way to tell him they weren’t a part of it and that they stood against it.

In the end, James said the continued diversification of the department brought on by the consent decree helped change the department.

“When you had that big influx of Black officers on the police department, it helped change the culture, because my incident — hitting somebody in the mouth in the FOP parking lot — wasn’t the only one,” he said. “So people learn, hey, there’s more Black officers on the department and they’re not going to put up with x, y or z.”

Bob O’Neil was another Black officer who joined the Louisville Police Department in 1984. There were issues of racial bias and discrimination on the police force, he said, but new officers often feared they’d lose their jobs or stall promotions if they spoke up without concrete evidence.

“You’re here to protect the public. With those types of biased attitudes, that can’t be done in a fair and legal manner in most cases,” he said. “People say, ‘Well, that’s his beliefs.’ Well, with that type of belief, you can’t really treat people fairly.”

O’Neil, who spent 20 years with Louisville’s force and is now a detective with the Audubon Park Police Department, said a mix of openly biased officers leaving and more inclusivity-minded officers getting promoted improved the Louisville Police Department over the years.

Wallace, of Showing Up for Racial Justice, said while there was a certain tolerance among many white Louisvillians at the time for Klan activity, there was also a lot of opposition put forth. Over the decades, that pressure on the police to watch its ranks has mounted. After the news of the two Sheriff’s Office officers in the Klan broke, she knew the department would have to get rid of them, that they would not keep their jobs as Klan members had in the past.

“They had to do it because it’s a PR nightmare now. After the Black-led uprising of last summer, they have to start acting differently,” she said.

Keep Louisville interesting and support LEO Weekly by subscribing to our newsletter here. In return, you’ll receive news with an edge and the latest on where to eat, drink and hang out in Derby City.