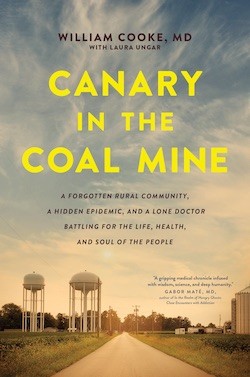

Dr. William Cooke sees what happened in Austin, Indiana in 2015— a small town 30 minutes away from Louisville — as a warning sign. Opioids swept through the town — something that’s identical to rural communities across the nation — and Hepatitis C and HIV followed. It didn’t happen overnight. But the situation was swept under the rug, Cooke said, and something that was preventable exploded into a full-blown crisis — one of the most devastating HIV outbreaks in the country. Cooke — who was the lone physician in Austin at the start of the epidemic — just released a book about his experience, “Canary in the Coal Mine: A Forgotten Rural Community, a Hidden Epidemic, and a Lone Doctor Battling for the Life, Health, and Soul of the People.” LEO caught up with him to talk about the beginnings of the crisis, what the town is like now and what other communities should do to avoid what Austin experienced. The interview is edited for length and clarity.

LEO: Let’s start with the earliest days of the twin epidemics. I’d imagine things were bubbling for a while, but after the initial wave of positive HIV tests, what was the town like and what did you do to try to help the situation? William Cooke: There was a lot of fear, panic, confusion, a lot of backlash against marginalized people that were really at the center of the crisis. The people who had basically been living in social isolation for most of their lives. So that was the atmosphere — a lot of fear, confusion and anger. That that was happening to their town, to their community, to their county, to our county. I had a particular vantage point where I was able to see this coming, so it wasn’t this huge surprise to me. But I think it caught a lot of the community off-guard, and then the fact that HIV had kind of disappeared from the public view for a couple of decades. That lead to some of the confusion and stigma — how it was spread and some of the misconceptions about that. So, people were afraid to casually contract HIV. They really didn’t want to be around anybody that had HIV out of fear that they would somehow contract HIV from being casually around them, so I thought it was really important to honor the humanity of the people who were suffering. I knew the community was a compassionate community — most people care about their neighbors — but it’s easy to stigmatize someone who you don’t see as your neighbor…So, one of the things we did early on was to really educate the community on how HIV cannot be spread, so I was really vocal about how HIV is not in sweat, it’s not in saliva, it’s not in tears, you can’t contract it from a surface. And really the only way you can contract HIV is if you share blood or sex with someone. And I think that helped people be around people with HIV and show them compassion. The family members that I met with, I made sure to let them know that if their loved one was upset, if they were crying and showing emotion, that they didn’t have to be afraid of holding them.

What were the strategies that were implemented to slow the spread at the time? I’d imagine testing was ramped up, and probably a clean needle exchange happened as well? Yes. Building up to 2015, we saw it coming. Public health care specialists saw it coming because we saw a surge in Hepatitis C, and Hepatitis C is spread the same way as HIV is spread, but it’s more contagious. So, any community that has a high prevalence of Hepatitis C is at risk for an HIV outbreak — it’s just a matter of time. So, from 2010 to 2015, we saw increasing numbers of Hepatitis C. Public health experts — the U.S. Department of Health, myself — we were calling for help. We were asking, ‘Please, do something, before it’s too late.’ But nothing was ever done. And then the HIV outbreak occurred, so we knew we needed to connect with people who were living off the grid, so we needed to develop resources and access points that felt safe to them. So we identified my office, the emergency department, two behavioral health organizations and the health department that could develop a syringe services program where people could access sterile syringes — not so they could use drugs; they were using drugs already. It wasn’t to allow them to use drugs but to allow them to make a healthy choice to not share a used syringe that could put them at risk.

What does the situation look like now? Well… they just closed our syringe service. So, we’re a little frustrated because we had developed a really thriving, successful response. One of the first things I was able to accomplish was connect with people with lived experiences to bring them into the response. Through that, we’ve grown a community recovery organization called Thrive, which is now one of the largest, most successful recovery organizations, not just in the state, but in the country. It’s recognized for their work throughout the country. They are asked to give talks and stuff in other places. These are people who were injecting drugs a few years ago, and now they are taking responsibility for their community and helping with the response…New HIV cases went from 181 that first year down to only one last year. Hepatitis C cases went from 250-300 cases down to less than 75 last year, so we’ve seen that decrease significantly…What we know is that in every county in Indiana that does not have a syringe service program, they’re seeing increasing cases of Hepatitis C, and, again, it’s just a matter of time before they start seeing HIV cases, as well. In the counties that have syringe service programs, those numbers are holding steady or going down. So, it’s further evidence that works.

There are many communities that are flooded with opiates right now across the United States. And those places seem at risk for spiraling. Was writing the book sort of a way to express that and inspire people to take preventive measures and keep that from happening? Yeah, so I called the book ‘Canary in the Coal Mine’ because Austin and Scott County was the canary to give the warning to the rest of the nation to pay attention when something bad is happening. There’s an unhealthy environment right now. Coal miners took canaries into the coal mines to know when the environment became unhealthy, so that they could take action. What happened in Scott County in 2015 should be that canary to the rest of the nation. •