To wander the winter-worn paths, bare forests and rock outcroppings of Rose Island in Charlestown State Park in Southern Indiana is to walk with myth, memory, history and a black bear named Teddy Roosevelt.

Along with inter-connecting tales of visiting Aztec Indians, a banished Welsh prince who showed up here from either Florida or Mexico, and the found skeletons of six of his Welsh soldiers with brass coats of arms among their bones.

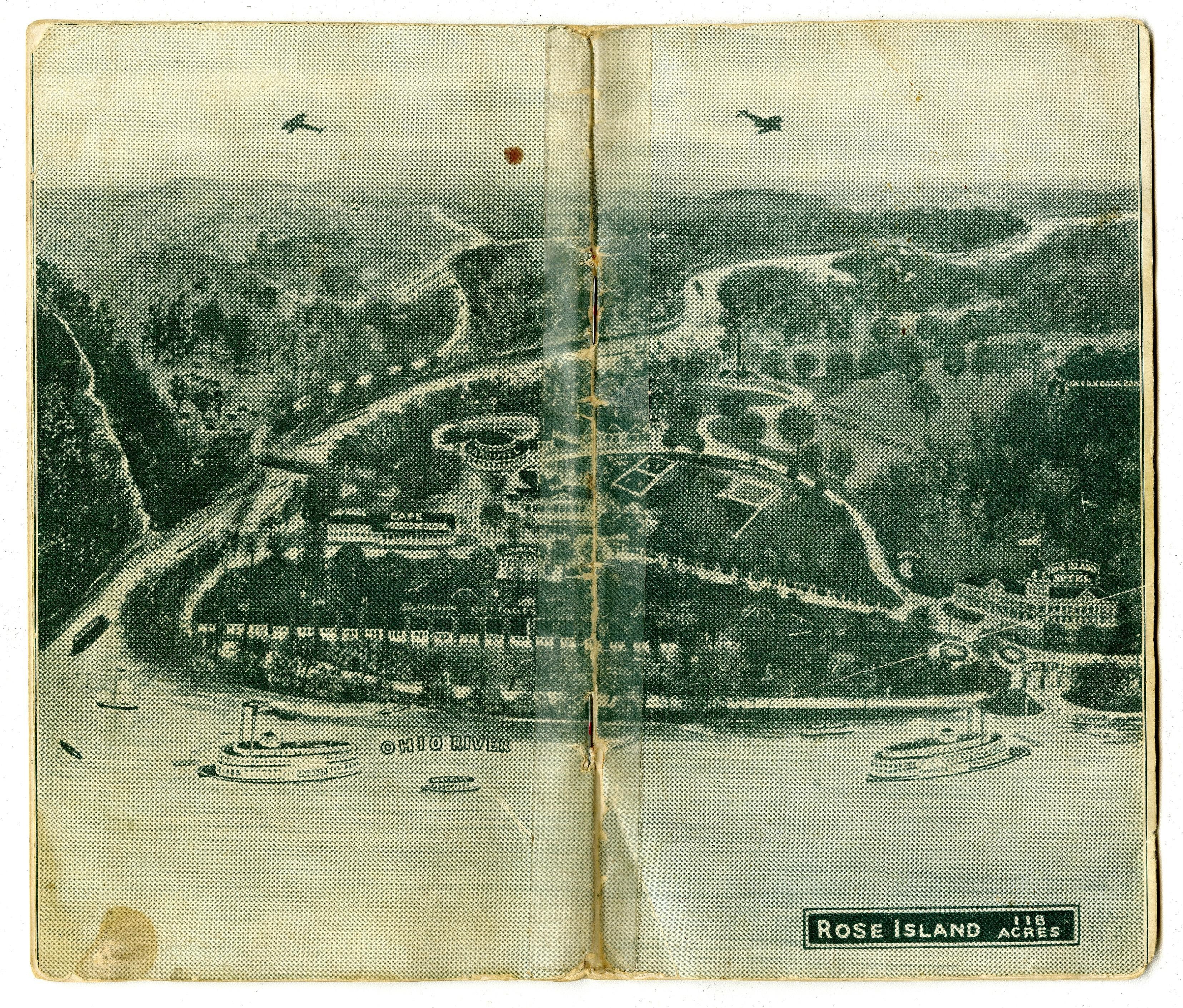

Add in possible ancient mound builders, a massive stone fort, Devonian fossils and karst sinkholes, a very popular, 1930s Kentuckiana resort washed away in the 1937 Flood, an historic swimming pool, 12 West Indian monkeys, a Florida owl and an alligator; presumably not a native.

Forget not the “Devil’s Backbone,” a bony precipice that rises almost 300 feet above all that, real and imagined, a steadily narrowing stretch of trail and jagged rock above the Ohio River offering a 10-mile visual sweep of the Kentucky shore. Yes, as legend insists, that land was cursed by the devil, but also provided the perfect hiding place, even eight centuries ago, to see all that was coming down the river without being seen.

If all of that reads like too much history to be assigned to one small Southern Indiana peninsula gently pushed out into the Ohio River 14 miles above Louisville, well join the crowd; there are doubters.

But it collectively makes too good of a story to just surrender it to humorless, bookish cynics who demand verifiable facts over romantic legend. All you have to do is walk the land, feel its ghosts, to know that truth doesn’t belong here.

Who needs it? Why ruin the fun?

It is, after all, entirely possible that wandering Aztecs and Welsh soldiers hung out around here centuries ago. No one has ever absolutely, definitively proven those stories wrong. Remember, Rose Island, which once hosted 135,000 visitors a year as the place to go from Louisville and Southern Indiana, isn’t even an island — and more on that later — so why sweat the historical details?

Beyond that, the larger Charlestown State Park, with its seven woods-and-water hiking trails and campsites, has a history all its own. Its 5,100 acres were carved in 1996 from a more than 10,000-acre Indiana Army Ammunition Plant promoted by a far-seeing President Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1940 — which, if you look at the big picture, was well before the bombs fell on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941.

At its peak in World War II, it employed 27,000 people, great swarms of them forever coming and going, many riding the train up from Louisville, others living in converted chicken coops. The plant stayed active during Korean and Vietnam wars before being shut down and cleaned up, eventually creating the booming River Ridge Commerce Center and rejuvenating its quiet, 148-acre neighbor, Rose Island.

It’s not all speculative history and mystery. It is possible to stand on Rose Island on a quiet morning and see some verifiable remnants of its amusement park past. There are crumbling fountains covered in moss, the cement blocks that once supported that long, rickety wooden suspension bridge over 14 Mile Creek — the toll 25 cents a head. You can see the twisted strands of metal bars jutting up from a thick layer of brown leaves, all that remains of the cage that once held the black bear, Teddy Roosevelt.

The old, outdoor swimming pool, 110 feet by 42 feet of filtered water and touted as “The Best in the Midwest,” is now filled with crushed gravel. It touches both worlds; a ghost-like rectangle in the middle of a growing forest, its curved ladders still ready for the next swimmer.

Once imagination takes deep root you can wander near the Ohio River landing, over by the massive stone columns that once held the arched R-O-S-E-I-S-L-A-N-D sign. Stand there and listen for the steamboat whistles, the excited chatter of its thousands of Sunday school picnickers eager to push onto shore; the fine orchestra music that once floated over a resort hotel, a dance pavilion, a horse-drawn merry-go-round and 20 guest cottages with screened porches and modern kerosene ranges, all now vanished.

For hundreds of years before those paddle-wheel boats, Native Americans used the Ohio as a major transportation and trading route, fought bitterly with one another, and built mound villages along parts of its 981 miles.

In the winter of 1668-69 the French explorer Rene Robert Cavelier de La Salle — who was seeking a route to China by the way — supposedly led his men down the Ohio River, perhaps as far as Louisville. Were they the first white men to see the river? Another claim under dispute.

But if you stand on the Rose Island shore on a quiet morning and shut your eyes, you’ll have no trouble seeing de Lasalle glide past. Stand a little longer and you might see George Rogers Clark float by, or give a little more thought to his brother, William Clark and U.S. Army Capt. Meriwether Lewis, who met about 14 miles south on their way to Missouri and beyond in America’s greatest voyage of discovery. We so often discount or ignore our valuable place in American history.

Spoiler alert ahead...

A modern-day walk down to Rose Island is most easily accomplished on Trail Three — although there is a woodland path. Trail three provides a very steep asphalt road, a needed maintenance entrance offering glimpses through the skinny trees of houses on the Kentucky shore.The trail drops down a few hundred feet, takes a sharp turn to the left and thankfully bottoms out near another historic marvel; a gangly, 357-foot, double-span, 107-year-old bridge that was moved from Portersville, Indiana to Rose Island in 2011 so hikers could get across 14 Mile Creek.

Hiker Warning: The walk back up the asphalt road seems about twice as long and difficult as it does coming down.

The apocryphal Rose Island past is a matter of some dispute. If you are to believe one Zella Armstrong, author of the 1950 book “Who Discovered America? The Amazing Story of Madoc,” the gathering point of much of the Rose Island speculation, there were no such easy paths onto Rose Island around 1170 when the Welsh prince Madoc first showed up.

History — or at least Wikipedia — explains that Madoc’s father, Owen Gwyneth, Prince of Wales, had 22 kids with two wives and four mistresses. Things got a little contentious around the house, so one son, Prince Madoc, sailed west with some 1,500 companions, landing in present-day Florida or maybe Alabama, with another nebulous source mentioning Mexico.

According to Armstrong, once in this new world, Madoc’s Merry Band of Welshmen was continually driven north and west by Native Americans, until coming across that protective spike of land that would become Rose Island.

Stay with me here.

That location also didn’t suit the local Native Americans, who drove out the Welsh, killing six of them in a battle near Sand Island and the Falls of the Ohio where the Welsh skeletons and 850-year-old armor plates were supposedly found in 1799.

Spoiler Alert: No one since has any idea where all the Welsh went, or whatever happened to all that armor.

But thus began the tale — helped along a bit by no less an authority than George Rogers Clark — of the White Indians of yore, a tale that nicely refuses to go away.

The supposed Aztec arrival here maybe 400 years after the Welsh were pushed out doesn’t add much real coal to this historical fire but is often shoveled with a straight face.

That legend — often mentioned in old Courier Journal newspaper text without real attribution — says the Aztec Chief Montezuma, a South American empire builder of some renown, established the furthest northern outpost of his nation at, you guessed it, Rose Island. That story goes that the Aztecs lived there on caught-fish and home-grown corn until the unhappy Native Americans began to drive them out, too.

Things totally fell apart when the Spaniard Hernando Cortez swooped in on Montezuma back home in Mexico, which required the Rose Island brigade go home to help save their nation.

It didn’t work.

Mystery of the mounds

One consistent thread in these Welsh and Aztec house-hunting stories is the report of a 150-foot stone wall constructed around the face of what became The Devil’s Backbone, along with trenches, mounds and piles of stones that could serve as observation towers.Much of that came from the pen of Indiana State Geologist E. T. Cox who visited The Devil’s Backbone in 1873 and soon announced the discovery of a Great Stone Fort, or, perhaps a little less modestly, the “Gibraltar of Indiana.”

Some of that supposition was due to the 1873 fascination of geologists and historians with “mound builders” of any source — and a total lack of the actual history of some areas. There were a lot of rock outcroppings on The Devil’s Backbone and the early settlers apparently needed some good stories to go with a bad life.

Such legends ran head-on into the doubting pen of one Gerard Fowke, the most-traveled archaeologist of his day, who visited the Devil’s Backbone about 1902 and wrote of the previous observations of men such as Cox:

“Both the plan and the description of this so-called fort are entirely imaginary... The reported walls of ten to seventy-five feet in height are only the natural outcrop of the heavy, evenly-bedded limestone.

“It seems incredible that a person connected in any capacity with a geological survey, even as a cook or mule-driver, could ever have made such a ridiculous blunder as to suppose them artificial.”

Those who still wanted to believe in Madoc, the Aztecs and The Gibraltar of Indiana only surmised all that rock and wall and mounds had been there, but the local farmers had hauled them away for their new houses and walls.

Evil and church picnics

Human intrusion onto Rose Island calmed down until the 1880s when, as described in a 1949 Courier Journal column written by Melville O. Briney, Fern Grove, a massive 1880s resort hotel that preceded the Rose Island resort, was built just above 14 Mile Creek.Old photos show the hotel to be a spectacular, three-story Victorian-era building with triangular roof lines and latticed front porches stretching the length of the building

All the accompanying publicity always mentioned Fern Grove as a place to get away from Louisville’s heat and humidity, as if 14 miles in those pre-air conditioned days really made a difference.

Named for the thick groves of ferns around it, the resort, mostly used as a church camp, its 100 acres “more or less” was purchased from an Ohio couple by Falls City Ferry Company for $1,300.

Often an individual church would charter an entire boat. Picnic baskets in hand, its members would head upriver on a two-hour cruise, if not some direct hiking confrontation with The Devil’s Backbone and that narrow path along its top labeled “Lover’s Lane.”

Alas, as Briney pointed out, evil could even raise its head on a church picnic:

“All Sunday-school picnics were pretty much identical until that famous summer when the Episcopalians introduced dancing on their boat rides. To say there was a sensation is gross understatement. But while the older members of the somewhat sterner sects clucked and shook their heads in disapproval, their young flocked to join the outings of Calvary, St. Andrews and Christ Church.”

The modern-day signage on Rose Island points out where that massive Fern Grove Hotel once stood, its back pushing up against The Devil’s Backbone, but the old photo makes the hotel seem just too big for the space. Nothing of it remains, but it somehow still doesn’t seem to fit.

Then came along one David B. G. Rose, a guy who parlayed a paper route as an 8-year-old in Nicholasville, Kentucky, into a newspaper delivery franchise, eventually becoming director or CEO of 20 Louisville companies.

His success included founding the Standard Printing Company with $75 in 1900 and building it into a multi-million-dollar printing company, the largest in the South. His legacy includes selling to Louisville at the cost of the 65 acres of land that became the Shawnee Golf Course, and organizer and president of the Falls City Ferry Company.

Rose was a guy who always dreamed big, knew all about Fern Grove and believed it needed a boost. There were also rumors that some guy from out of town was about to buy it. Forget that. The headline in the 1923 Courier-Journal proclaimed:

“Rose Is To Build Summer Resort

Printing Man Buys Fern Grove for Amusement Park”

No price of the purchase was mentioned, but Rose did pledge to spend $50,000 in 1920s money for a getaway resort and summer amusement park. Subsequent stories said he spent $250,000.

Promised improvements included a bathing beach, augmented water supply, tennis courts, a first-class restaurant and cottages for rent. As an added ornamental attraction all the trees facing the river would be whitewashed.

Oh yeah, that small peninsula of very attached land would become... yes... “Rose Island.”

Now a ghost attraction

Getting there would be made much easier; he had his whole fleet of ferry boats ready and the steamer “America.” The paddle wheeler the Idlewilde, later the Belle of Louisville, would make regular runs from the already popular Fontaine Ferry amusement park to Rose Island.Those in cars could drive up Utica Pike in Indiana to Charlestown, drive down that steep hill on what is now trail three, park along 14 Mile Creek and walk the rickety bridge. On the Kentucky side, Rose offered three ferry trips a day from the newly named Rose Island Road.

On the busy days 4,000 people paying 50 cents each might visit the amusement park. It quickly grew to include a dining hall holding 400 people, a miniature golf course, an ice storage area, a rock crusher to create gravel paths, a roller coaster, that motley zoo, rented rowboats, pony rides, a garden for fresh vegetables, a dairy herd for milk and flowers and roses — yes roses — grown along a forest walkway flanked by upright pillars and metal arches to hold them.

It was all special and grand and very busy until the Great Depression crushed our national economy and the 1937 flood buried parts of it beneath 10 feet of water

Its visitors became mostly the curious in small boats. Despite several announced attempts to revive it over the years, Rose Island rotted away, buried in weeds, invasive shrubs and neglect. It’s old swimming pool, surrounded by a tall, rusting metal fence, became filled with brackish water and rotting leaves. Above that brown water rose a round metal stand, tilted to one side; the place where hundreds of kids once stood trying to spin others off into the water, now all crushed gravel and ghosts.

Once the Portersville Bridge was put into place, the grounds restored, Rose Island became alive again. When walking the bridge, its wooden planks vibrate, echoing off the water below and into the surrounding hills.

Ahead, bending back toward the river, waits a replica of the Rose Island sign that once greeted visitors scrambling off the paddle wheelers. It offers anticipation and short history lessons; the Miami, Delaware and Shawnee Indians were present in Clark County; the Ohio River once dropped to only one foot nine inches in depth during the drought of 1881.

Another nearby sign holds the Rose Island rules — a period piece in itself:

No Gambling Will Be Allowed

No Drinking Permitted

Animals Must Not Be Molested

All Other Property Fully Protected

As for The Devil’s Backbone, the sign attached to the steep trail leading up to it warns with mixed results: “State Park Boundary. No hunting or trespassing.”

No Lover’s Lane.

No signs of the devil.

No way.

Scattered around the entire site are blue, circular discs attached to poles marking the depth of the 1937 flood, a few so high up they can’t be touched. Closer to the river are metal arches rising above new, concrete pillars; smaller replicas of those that once held the Rose Island roses.

For all that, the physical Rose Island restoration is sparse. There’s just not much left. The tall bare trees are lovely, most of it second and third growth, all of them leaning toward spring with no visual proof there either. The incoming wildflowers are said to be magic. But the old mysteries linger. The mind wants to see more than what is available.

That’s best accomplished sitting on a fallen log, the woods silent, the gray Ohio River disappearing around a bend, taking both the past and the future with it. •