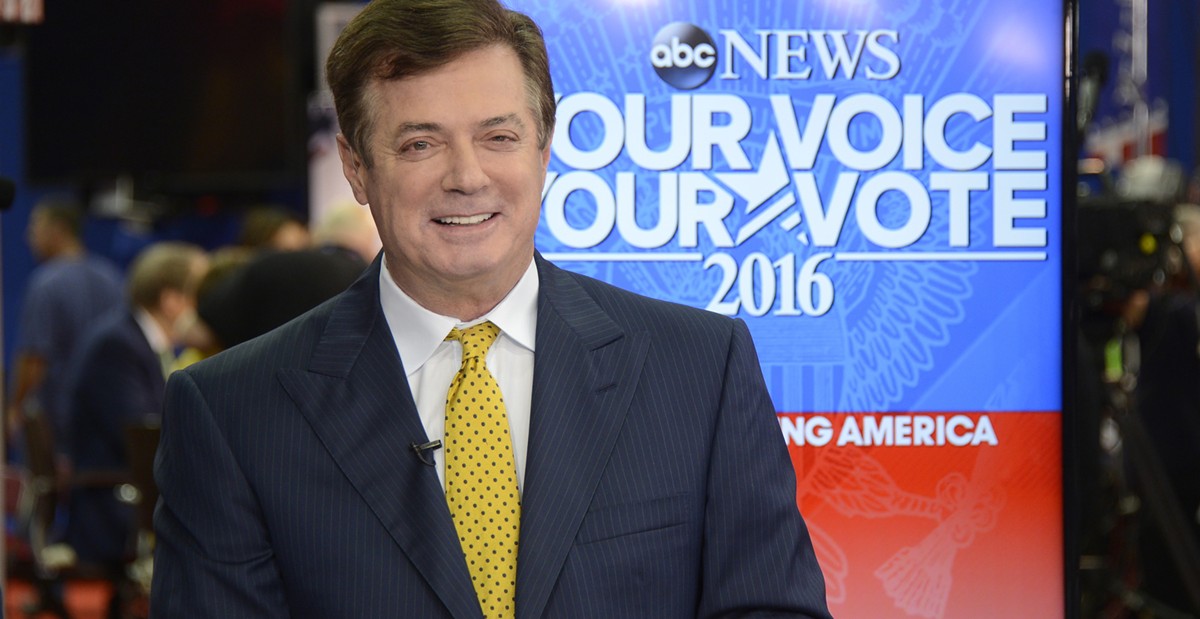

News that Paul Manafort was testifying last week to the U.S. Senate intelligence committee takes me back to March 2016 when I saw that he was joining the chaotic Trump campaign as an advisor on delegate and convention strategy (he later became campaign manager). I, unlike most Americans outside the beltway, said: “Hey, I’ve heard of that guy!” Later, when it was reported that Donald Trump Jr. had invited Manafort to a meeting with a bunch of shady Russians, including a rumored former Russian counter-intelligence agent, I was not surprised. In fact, I could only think that a room full of nepotists, ex-spies/lobbyists and people-on-the-take is Manafort’s most natural milieu.

I did not know Manafort because of his long history in GOP presidential campaigns from Gerald Ford to the elder George Bush, discussed in Franklin Foer’s excellent Slate essay “The Quiet American.” No, I first took note of him years ago because of events taking place in the 1980s, 7,000 miles away in Africa.

Although my research is now mainly in legal history, back then I was a UofL graduate student, an occasional contract researcher and anti-Apartheid activist interested in U.S. foreign policy, especially the competition of American and Soviet policy in Africa during the Cold War. This was the subject of my master’s thesis — a swashbuckling tale of the funding of the Volta Dam in Ghana during the Eisenhower and Kennedy administrations. OK, substitute “overly detailed and kind of boring” for “swashbuckling.”

Manafort attracted my notice because of the efforts of his former D.C. lobbying firm, Black, Manafort, Stone and Kelly, to sell the Reagan Administration on Jonas Savimbi’s attempt to overthrow the Soviet-aligned government of Angola. (Yes, the Stone is Trump loyalist, Roger Stone). The well-coifed Manafort was the point man and earned a $600,000 fee from Savimbi’s UNITA movement by convincing Reagan and U.S. conservatives that they were heroic “freedom fighters” struggling to create a model democracy in Africa. Reagan gave Manafort’s clients a $25 million military aid package, including several of the then-prized Stinger anti-aircraft missiles. (Just like the Islamic fundamentalists fighting the Soviets in Afghanistan received — we all remember how well that turned out).

While working for my former thesis advisor as a researcher on a historical dictionary of Angola, I learned more about what Manafort had omitted from the story of his client. This included Savimbi’s brutal authoritarian rule over the areas under the control of his forces, his past as a Maoist (until the Chinese money ran out) and the fact that supposedly Communist Angola had very cordial relations with the U.S. company that ran its oil industry, Chevron. In one dramatic story, Savimbi reportedly rounded up internal dissidents and burned them as witches. Now, that’s a political witch-hunt, Mr. President!

Manafort continued his business of putting lipstick on pro-Western dictators, such as kleptocrat Mobutu Sese Seko of Zaire and Ferdinand Marcos of the Philippines, with such success that it was impossible to study the darker side of U.S. foreign policy without running across him. In 1992, he was featured prominently in the Center for Public Integrity’s landmark report “The Torturers’ Lobby: How Human Rights-Abusing Nations Are Represented in Washington.” His mother must have been so proud.

After the cold war, Manafort re-engineered his business for a new line of dictator — authoritarian leaders in the former Soviet republics. Soon he hooked up with Vladimir Putin’s favorite Ukrainian, pro-Russian Viktor Yanukovych. According to Ukraine’s anti-corruption bureau, Manafort received $12.7 million over a decade to install Yanukovych as president in 2010 and to defend the imprisonment of his opponent, Yulia Tymoshenko. (Tymoshenko might have been lucky; another Yanukovych opponent, Viktor Yushchenko, was a dioxin-poisoning victim the year before Manafort was hired.)

Manafort was still on the payroll in 2014 when riot police fired on protesters, killing 53 people, and Yanukovych was forced to flee to Moscow.

One can only imagine suave Paul rubbing up with former KGB agents he once passed in the airports of Kinshasa or Manila. I’m sure they laughed about old times, sharing stories of daredevil days of their Cold War youth, before turning to the business of shoveling money out of the treasuries of these new and unsuspecting states.

Which returns me to the Trump Tower meeting in June 2016. While Don Jr. could be described charitably as an upper-class twit, and Jared Kushner as an overconfident political novice, Manafort has been in so many shady meetings like this it would take IBM’s Watson to keep up with them. In fact, he could dictate the “Petersen’s Field Guide to Bag Men, Contract Spies, Cutouts, and Other Shadowy Figures” to a secretary over a long weekend — with enough spare time to draft a script treatment for a “House of Cards” story arc.

So, while Don Jr. and the Russian lawyer set up the crowded meeting, the real principals were likely campaign manager Manafort and Rinat Akhmetshin, a pro-Russian lobbyist with ties to Putin’s intelligence apparatus. Some stories suggest Manafort was fiddling with his smartphone all meeting — maybe texting LOLs to Akhmetshin? (Although perhaps he was taking the meeting notes he reportedly has turned over to the Senate.)

Many of the news stories speculate on the legal liability of various individuals in the Trump inner circle, but that misses the point. Special Counsel Bob Mueller has surrounded himself with tough investigators who, like him, made their careers prosecuting organized crime. If there was a conspiracy to collude with the Russians, any major prosecution will focus first on the Trump campaign as an organization, with all the various acts tied back to it. In the middle of the web (as either lead conspirator or Mueller’s star witness) will be campaign manager Paul Manafort, still attracting my attention all these years later.