Early on in Larry Muhammad’s finely-crafted play about the legendary jockey Jimmy Winkfield, Winkfield (played with indefatigable energy by Gary Brice) tells us that he’s spent most of his life on the run. The Klan, he says, chased him out of Kentucky. The Commies chased him out of Russia. And the Nazis chased him out of France.

Those three episodes in Winkfield’s life just barely begin to sum up an amazing life. Muhammad’s program note says that Winkfield’s “60-year career is arguably the most fascinating saga in thoroughbred racing.” But that’s an understatement: His career is indisputably one of the most remarkable tales in the history of any sport.

The quick facts: Winkfield was the last African-American jockey to win the Kentucky Derby, a feat he accomplished two years running, in 1901 and 1902 (matched by only four other jockeys, all of whom are, like Winkfield, members of the Jockey Hall of Fame). Fleeing racist death threats, Winkfield moved to Russia in 1904, where he raced in the silks of Tsar Nicholas II, winning all of the signature races in Russia and Eastern Europe multiple times. He fled the Bolshevik Revolution — driving a herd of more than 200 thoroughbreds from Odessa to Warsaw.

He settled in France, married a Russian heiress and started racing and training from a château on the outskirts of Paris. By the time he retired from racing to focus on training, he’d notched 2,600 wins. He eventually fled the Nazi occupation of France and wound up back in the United States, a forgotten legend, mucking stables in South Carolina (where he and his wife had to conceal their marriage, which was, of course, illegal). Eventually, his acumen as a trainer rehabilitated his financial fortunes, and he was able to return to France and resume training at his château.

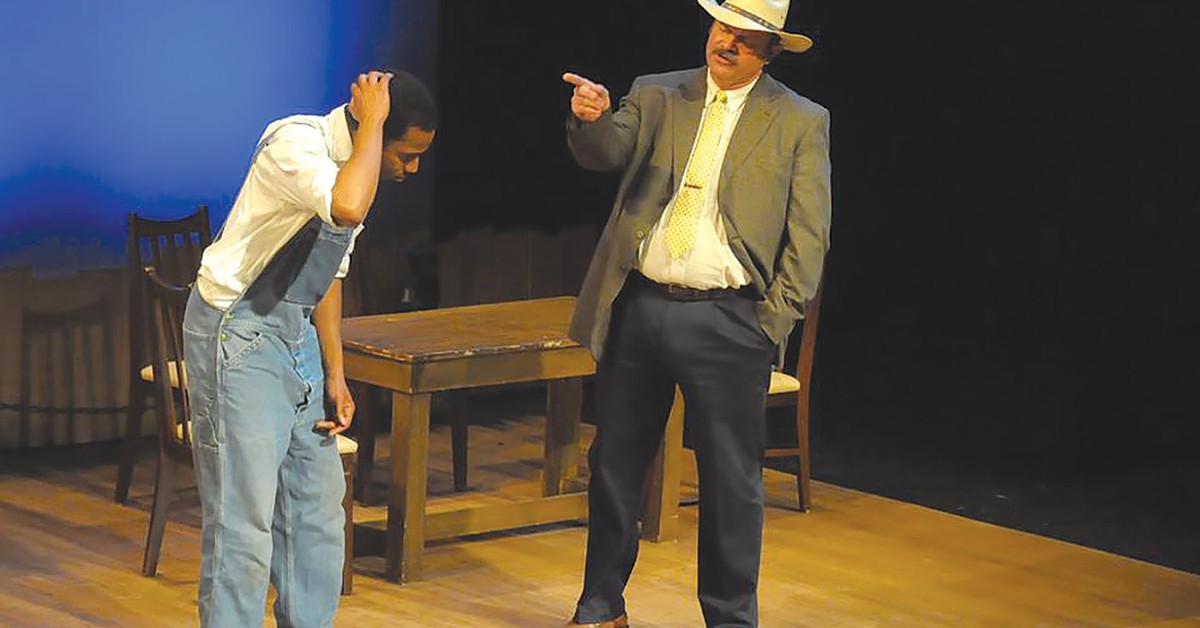

It’s a great story. And Muhammad has turned it into a compelling piece of theater. He starts the action at the lowest point in Winkfield’s career. It’s been nearly a half-century since his Derby glory, and he’s an old, unknown black man mucking stalls for a casually racist South Carolina horseman named Beauchamp. Their opening interchanges — Winkfield’s cautious diffidence, and Beauchamp’s swaggering arrogance — place us squarely in bitter heart of Jim Crow race relations in the ‘40s. Everything about the way Gary Brice (Winkfield) and Ernie Adams (Beauchamp) interact on the stage captures the chilling physicality of the modesty and brutality of that era. It’s a powerful start. And throughout the play director William P. Bradford II and his cast (several of whom play multiple roles) shape every scene with convincing authority in this production from Kentucky Black Repertory Theatre.

No matter the setting or the situation, Bradford and his team (set designer Eric Allgeier, costume designer Josh Crowe, lighting designer Nick Dent, and sound designer Ken Atkins, whose masterful work in evoking the sounds of the racetrack and the musical soundtrack of the 20th century shapes and frames the story as it jumps back and forth across decades), finds exactly the right tone. One scene finds Russian nobles (Francis Whitaker and Spencer Korcz) exhorting Winkfield to save their horses from being carved into steaks by the Bolsheviks. In another, Tom Pettey, Tom Luce and Tim Stone portray Nazi officers who have requisitioned Winkfield’s Parisian stables with perfectly clipped Prussian precision. And in a delightfully burnished French interlude between the wars, we see Winkfield during a period when his château was frequented by the likes of Josephine Baker (Sidney Edwards), Paul Robeson (Tyler Madden) and Bing Crosby (Patrick Alred). And all these scenes have a fully-realized feel.

But the heart of this time-shifting story plays out in 1940s America. That part of the story is populated by Winkfield’s co-workers and boss, all of whom dismiss him as an old fraud, and by his wife Lyddy (played with cunning force by Samina Raza). And it’s in those settings that Muhammad takes us into the spirit of this epic figure.

In the stables, Winkfield’s foils are a couple of hands named McLemore (Joe Monroe) and Travis (Marcus Orton), whose every appearance on the stage is a joy to watch. Monroe and Orton give no-holds-barred performances in their skeptical mockery of the old man’s claims, and that mockery in turn gives Brice’s Winkfield an opportunity to bring us into his thoughts about racing — and race. And it’s here that Muhammad takes us into the world of racing strategy as Winkfield conspires with young Latino jockey Milo (Francisco Juarez) to build the odds on a horse he alone has recognized as winning a big race.

Meanwhile, in the shuttered secrecy of their home, we see Lyddy and Winkfield grappling with their plight, fighting through a set of fears and challenges that must have seemed crushing and insurmountable at the time. And it’s in these scenes that we glimpse the intimacy, guile and energy that enabled this unlikely couple to prevail over their circumstances.

It’s a powerful story of unflagging effort — but despite Winkfield’s eventual moment of reconciliation with Beauchamp, Muhammad doesn’t avoid the tale’s darker elements. In the 1960s, Winkfield was invited back to Louisville by Sports Illustrated to an event at the Brown Hotel. He was at first denied admission because of Jim Crow racist policies. That event is deftly recounted here and includes nice vignettes from Tyler Madden (the African-American doorman charged with enforcing the policy), Patrick Alred (playing longshot jockey Roscoe Goose, the only white person in attendance who recognizes and respects Winkfield), and Owen Kane as the racing official who ignores this legendary figure — who died in 1974 at his château at age of 91.

“Jockey Jim” runs through May 6 at the Henry Clay Theater, 604 S. Third St. For information: 727-7972, or email [email protected]