The internationally recognized British-Nigerian artist Yinka Shonibare CBE uses Dutch wax fabric as a signature in his works. He has called the Indonesian inspired batik printed fabrics “the perfect metaphor for multilayered identities” (yinkashonibare.com/press). The Dutch, in the late 19th century, mass produced the brightly colored patterned cloth to sell in Indonesia without success. In turn, the fabrics were offered to the West African market where they were embraced and are now commonly associated with Africa. This complexity of identity, globalization and questions of authenticity inform Shonibare’s work.

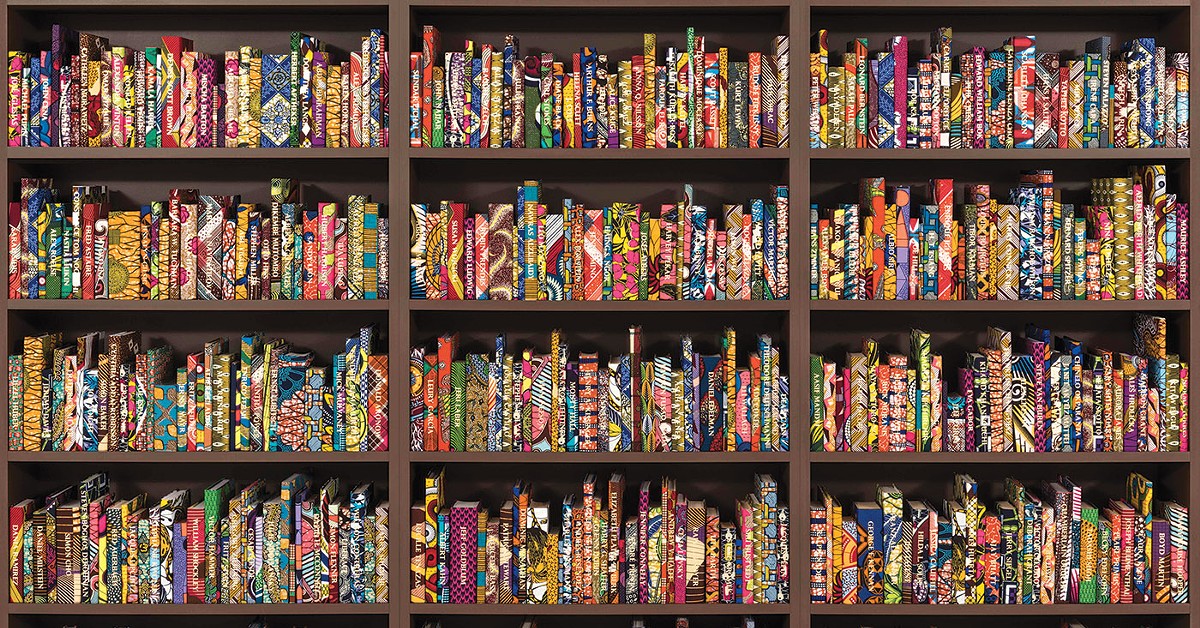

In “Yinka Shonibare CBE: The American Library,” the concepts of contribution, authenticity and growth is addressed. Over 6,000 books of various thicknesses and heights are covered in an array of Dutch wax fabric. On various spines, names are printed in gold lettering. The shelved books reside, in this case, in an original library space of the Speed Art Museum, thus layering time. The names inscribed are of people who are first- or second-generation immigrants to the U.S., people who participated in The Great Migration of the early 20th century, or of people who oppose immigration. The physical installation is accompanied by a vast database which lists the aforementioned peoples and their contributions to America. The contributions are scientific, artistic, literary, athletic, political and so forth. The database can be accessed by tablets that are stationed on wooden tables in the “library.” The database is also available online (theamericanlibraryinstallation.com), taking the installation beyond its physical space and emphasizing the truly global nature of humanity. By offering the data without editorial, a neutral space is created. Scrolling through the names and achievements is fascinating and engrossing. It is a bit jarring to then encounter a description of a person as opposing immigration in the midst of the plethora of contributions. It calls forth questions of entitlement, hypocrisy, fearfulness and human nature. The Dutch wax fabric then reminds us that these issues transcend the American experience.

Complementing the installation piece at the Speed Art Museum is a collection of his sculpture and prints. The sculpture of a ship in a bottle, “The Wanderer,” is a detailed model of the last ship to transport slaves from Africa to the U.S., despite the illegalization of the practice. The sails are made from the Dutch wax fabric, offering commentary on the textile’s appropriation and commercialization which propagated the slavery industry. “The Age of Enlightenment — Gabrielle Émilie Le Tonnelier de Breteuil, Marquise du Châtelet” is an effigy of the 18th century mathematician. The headless figure is seated, working at a desk with books, paper and quill. Her period dress is Dutch wax fabric, her left hand a prosthesis. Le Tonnelier de Breteuil, despite her “fault” of being a woman, excelled intellectually during the Age of Enlightenment. Again, the questions of hypocrisy and privilege arise; in spite of themselves, the “enlightened” elite were forced to recognize her abilities. Two large prints entitled “The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters (Europe/America)” are from a group of five images derived from Goya’s 1799 series “Los Caprichos.” The seated figure in each image is dressed in early 19th century attire rendered in the Dutch wax fabric. The sleeping figure is surrounded by wild animals, referencing the animal instinct that emerges without enlightenment. The layering of modern printing technique with classic imagery and vibrant color and pattern creates a tension between the old and the new, the accepted and the unexpected, the Western and the global. “Three Graces” is a freestanding grouping of three female, headless figures dressed in lavish Edwardian gowns which are also made from the Dutch wax fabric. The formal nature of the clothes is challenged by the seemingly exotic fabric, recalling that colonialism’s very fabric was composed of globalization. The sculpture “Food Faerie,” which harkens to the ancient Greek sculpture of Mercury, depicts a headless, winged youth clothed in Dutch wax fabric, bearing African mangoes on his back in a woven sack. Here, the messenger is Africa bearing its fruit to nourish the European culture and economy.

Shonibare offers wry commentary about the ongoing effects of colonialism, a period commonly viewed as historical. However, the political climate of America today is rife with its aftermath. “The American Library” provides tangible evidence in a subtle manner of America’s dependence on diversity and inclusion.

The show is co-presented by The Speed Art Museum and 21c Museum Hotel, featuring works from its collection.

‘The American Library’

Through Sept. 15

Speed Art Museum

2035 S. Third St.

Free with general admission

Times Vary