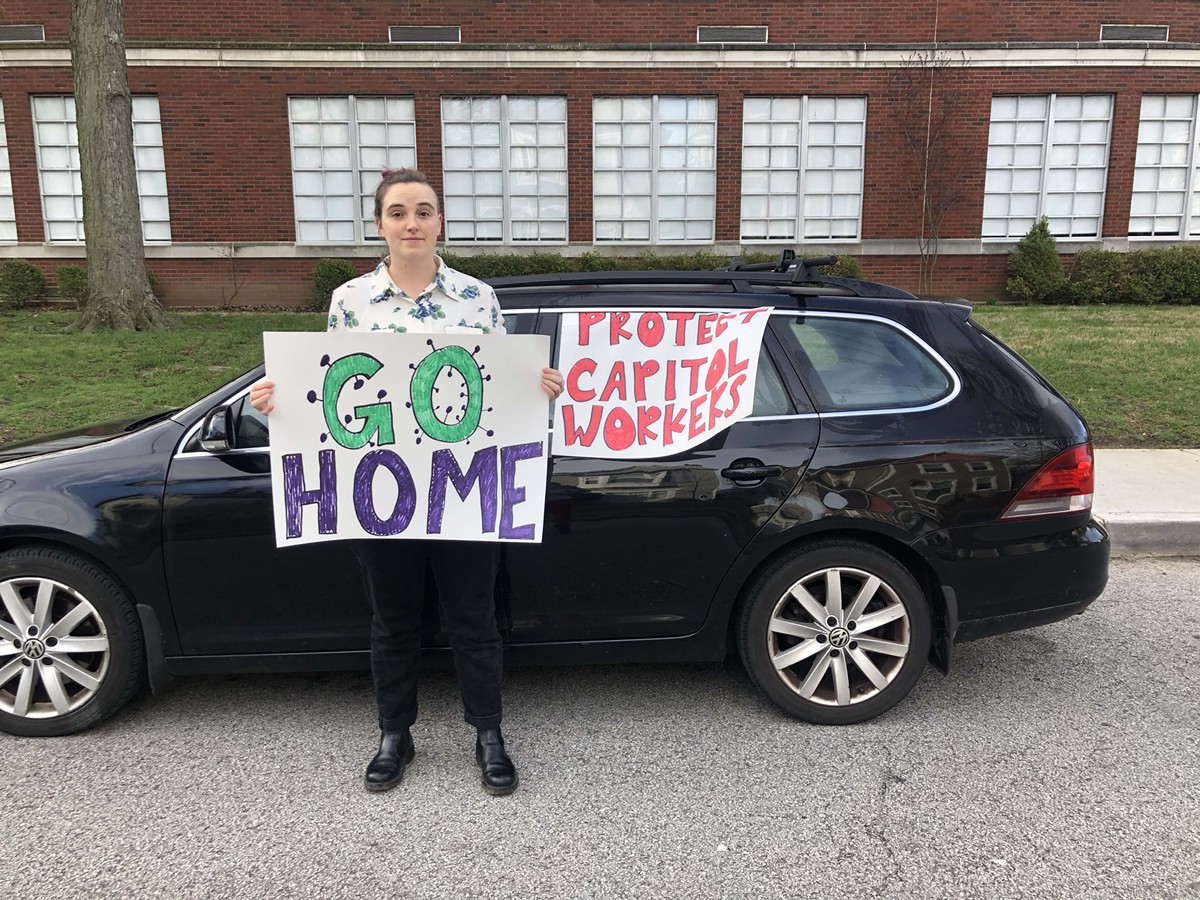

The poster board flapped from the black Jetta SportWagen’s windows as the car circled the Kentucky State Capitol building over and over again: “Protect Capitol Workers,” read one homemade sign. “Go Home,” said another.

The vehicle, driven by Beck Jones, was one of around 15 honking and circling the building last week where Kentucky lawmakers debate and pass hundreds of bills each year. This was how activists, unable to enter the Capitol, protested the legislators who continued to pass controversial bills in the midst of a pandemic.

Activists around Kentucky have had to find new ways to show the will of the collective in a time when traditional protests can be deadly but are still needed.

Despite the unusual method, Jones said that the caravan protest felt effective.

“The energy of people coming together around a shared goal felt really present and powerful,” said Jones, who is a member of Save KY Democracy, which organized the protest.

Protests are an important part of holding people in power responsible, say activists, but the challenges of social distancing can also make it harder for demonstrations to be impactful, as fewer people show up and people in power are harder to confront directly. Some groups, such as Indivisible Kentucky, a left-leaning organization with a focus on Congress, have stepped back from traditional protesting during this time.

David Horvath, a spokesperson for Save KY Democracy said, “This is a huge challenge. I certainly wouldn’t want to make it out to be something that’s a preferable way to do things, because we already have two hands behind our back some when we do activism.”

Chanelle Helm of Black Lives Matter Louisville said that in-person protests are still important. “It really can go on,” she said. But her organization has been focused on needed volunteer work, such as delivering groceries and supplies to families in need, as well as planning training to teach others how to organize during the pandemic.

Planning a social-distanced protest brings its own complications, but it’s especially important as participants cannot easily communicate with everyone once they’re on the ground protesting.

Jones, who is 28, said that technology is key but a hurdle in and of itself: some people with Save KY Democracy did not have much experience with messaging and meeting apps such as Zoom and Slack.

Other Louisville groups have been willing to take on the challenge of protest during the epidemic. Louisville Showing Up For Racial Justice and The Bail Project Louisville were two of the first.

On March 20, the two groups organized an action to demand the release of prisoners from the Louisville Metro Department of Corrections who were over 60, medically fragile or being held because they couldn’t afford to pay their bail.

The protesters, a small number of invited activists, stood 10 feet apart from one another in front of the Louis D. Brandeis Hall of Justice downtown, holding posters declaring “Jails Hurt Families” and “End Cash Bail.” One member had brought many of the signs, which were wiped down with hand sanitizer before being distributed.

There was no Facebook or Twitter post advertising the event beforehand in order to keep the group of protestors small, and the event was scheduled strategically for 8:30 a.m., when the sidewalks would not be busy with pedestrians who could potentially be exposed to any contagions.

“They would probably prefer that we’re just sitting at home on our computers,” said Sonja DeVries, an LSURJ member, “they” being people in power. “But we need to be creative, we need to find ways of collectively resisting.”

On Friday, after participating in a webinar with activists from across the country, and realizing that they should probably step up their social distancing efforts, LSURJ and The Bail Project created a caravan of their own — cyclists and drivers riding past Louisville’s ICE field office, the Hall of Justice and mayor’s office — to protest conditions at the jail.

Sharon Fleck, a board member with Indivisible Kentucky, said her group typically promotes and helps organize protests that other groups are spearheading, but she still doesn’t see any mass gatherings, like the Rally Against McConnell’s Corruption event that Indivisible helped host this February, happening anytime soon.

“Now is not the time to have large groups of people gather,” she said.

Indivisible will continue to promote other protest events, as it did with Save KY Democracy’s caravan.

“I think it’s a great idea,” she said. “I don’t think that it has the same impact as, you know, having 10,000 people at the Capitol the way we did a couple years ago.”

Activists have been able to harness other avenues of protest besides in-person rallies to their advantage, too.

The day before the caravan, Save KY Democracy launched a social media and communications blitz to notify legislators digitally and via phone and email about their demands.

“Interestingly enough, it seems like legislators are paying more attention to their social media handles right now,” said Jones.

And, Save KY’s efforts seemed to have paid off, or, at least gotten something back.

After the caravan on Thursday afternoon, House Speaker David Osborne announced that SB 1, an anti-sanctuary bill (one that Save KY is against), was likely dead for the session. No abortion bills would be addressed in the House on that Thursday either, said Osborne.

“It definitely feels like a win,” said Jones, acknowledging that Save KY Democracy probably wasn’t the only factor influencing Osborne’s decision, “and I also feel inspired that this protest and the social media campaign and lots of other people in their own ways are still finding ways to communicate to our legislature about what we want and need.” •