DISCLAIMER: The statements in this article are solely expressions of the author’s opinion after reading the relevant documents, which are all public records. The author is also poor and not worth suing. Thank you.

Recently, eight unnamed students from Covington Catholic High School sued various media celebrities and politicians, including Elizabeth Warren, for libel. These were students who were heavily criticized for a confrontation they had with a Native American activist group in Washington, D.C. The story, with video included, started off as highly critical of the Covington students and then, as more video emerged and Nick Sandmann (the student smirking in the MAGA hat) came forward to defend himself, the picture became less clear. Ultimately, the Roman Catholic Diocese of Covington found the students not to blame for the incident, and the media coverage died down.

But then Sandmann sued The Washington Post and several other media organizations for defamation, seeking over $250 million dollars. That lawsuit was dismissed a few months ago. The judge’s opinion was a nice summary of defamation law in Kentucky and found the complaint wanting in several respects — the statements were not of fact, but opinion, several of the statements did not refer to Sandmann as an individual, and the statements were simply not damaging to Sandmann’s reputation.

In short, as the judge explained, defamation requires more than just false statements — they have to harm your reputation. That means that the statements must be about you, must be false statements of fact and must be accusing you of things that, if believed, would damage your reputation.

Sandmann’s father said they would appeal, so that case is not over yet, and, in the meantime, the case filed by some of the other Covington students was recently dismissed by a federal judge. Despite this dismissal, the Covington students’ lawsuit is worth studying as an example of how lawsuits can be used to attempt to silence critics and how that tactic is allowed to run rampant in Kentucky.

If Sandmann’s complaint was bad — and it was — this lawsuit was even worse. It had everything that was wrong with the Sandmann lawsuit but with extra ridiculousness.

First, the statements complained of were clearly not defamatory — they did not open the students up to ridicule in the community. Take Warren’s statement — a tweet that stated: “Omaha Elder and Vietnam War veteran Nathan Phillips endured hateful taunts with dignity and strength, then urged us all to do better. Listen to his words.” The tweet linked to a Splinter video where Phillips talked about how the students said, “Build the wall.” The strongest language used in the video is that the students “harassed” Phillips. Is this really defamation?

Nah.

Defamation is a fact-intensive inquiry so the words used matter. Considering Sandmann’s recently dismissed lawsuit, it is hard to imagine how anything Warren said — even in the words used in the video she linked in her tweet — could be so injurious to someone’s reputation as to require her to pay them damages. The most “damaging” thing she said is that the taunts were “hateful.” Similarly, the video merely states that Phillips was “harassed” by “high schoolers.” That’s it. Wait, that’s it?

Second, even if these statements could injure someone’s reputation, were they statements of fact?

There are no details and no specifics.

She accused someone of using “hateful taunts,” which is a pretty subjective statement. Were they taunting or speaking? Were they being hateful or stoic or humorous? Is that a fact that can be disproved?

Unlikely.

But here’s the worst part of this lawsuit. The plaintiffs weren’t even named; they were anonymous. You can’t — and I cannot stress this enough — anonymously sue someone for defamation and be taken seriously. The allegedly defamatory statements must be about you. And not a group you’re part of.

In Kentucky — where both of these lawsuits took place, statements made about a group can apply only where the individual suing is clearly identified. Membership in some amorphous group is not enough for defamation unless the group is very small and every member of the group is equally impugned. “High school students” is simply too vague to sustain a defamation action. Naming Covington Catholic narrows the group down to 586 students, and Warren didn’t even do that.

What makes this lawsuit even more absurd is that the plaintiffs did not name themselves in their own lawsuit. How can we know if they have been individually impugned if we don’t know who they are? How can their reputations be ruined in the community if the community doesn’t know who they are? Only Sandmann’s name has ever been mentioned in any media coverage, and he identified himself.

The fun part is that this lawsuit was not dismissed even on the merits of the defamation claims. It was dismissed because they sued Warren, a politician and federal employee, who is immune from being sued for defamation if the statement was made in her official capacity, which this statement was. The lawsuit was clearly without any merit for so many reasons that the court dismissing the case was able to simply choose its favorite and didn’t even address the rest.

So, why file it? Why waste time and energy filing a losing lawsuit and for such a comically large sum of money?

I would say that it was to gain media coverage but, as noted above, these plaintiffs were anonymous. Perhaps it was simply to harass the defendants, force them into litigation and the costs that accompany it. If so, this lawsuit would be properly characterized as a SLAPP lawsuit. SLAPP stands for “strategic lawsuits against public participation,” and the term refers to lawsuits that are specifically filed to intimidate and silence criticism.

SLAPP lawsuits have a long and ignoble past, the most famous of which was the case New York Times v. Sullivan, a Supreme Court case that set the standard for defamation against public officials. That case was set against the backdrop of the civil rights Movement when public officials would use defamation laws to try to silence newspapers that reported on civil rights protests.

Although it did strike a heavy blow, New York Times Co. v. Sullivan did not end the practice of using litigation to stop public criticism, and so several states have enacted “anti-SLAPP” laws that provide a remedy to those who have been sued in a SLAPP lawsuit. These laws give the defendant an early opportunity to stop a lawsuit by showing that the statement they made was on a matter of public concern. The plaintiff must then show that, despite that, the plaintiff is likely to prevail. If the plaintiff fails, they may have to pay attorneys’ fees to the defendant, a nice disincentive for filing a frivolous lawsuit.

Without anti-SLAPP laws, defendants can only move for sanctions against the plaintiffs and their attorneys, which has a considerably high bar because a lawsuit is, by definition, not frivolous even if it is not based in the law as long as it consists of a good faith argument for the modification or reversal of existing law.

I’m not arguing that this bar should be lowered; attorneys should be able to argue that a law should be changed. But anti-SLAPP laws, limited to lawsuits intending to punish people for criticizing others on a matter of public concern, fill an important gap in existing law and allow for enhanced protection of the First Amendment.

Unfortunately, many states don’t have anti-SLAPP laws, including Kentucky.

What that means is that despite the arguably harassing nature of the Covington suit against Warren and others, they had no opportunity to dismiss the case early and have no meaningful way of recovering attorneys’ fees. So, even though they won the lawsuit, they did so at a sizable cost; lawyers aren’t cheap and these defendants, Warren included, had to hire local Kentucky counsel as well as pay their regular attorneys.

This lawsuit makes a good case (pardon the pun) for passing an anti-SLAPP law in Kentucky and perhaps federally. Otherwise, plaintiffs who want to harass those who criticize them can simply choose a state that does not have an anti-SLAPP law and use the courts to punish those who would speak against them.

John Oliver recently experienced this in West Virginia.

Ultimately, that case, and the Sandmann one before it, likely came about because individuals felt they were being punished unfairly in the media. But the media coverage did not accuse them of committing a crime or being dishonest or even hurting anyone. Basically, it made them look like jerks. And maybe that portrayal was unfair based on incomplete footage. But these lawsuits are a different story; they look like the reactions of children trying to punish those who have called out their bad behavior.

In Kentucky, there is no real remedy for this tantrum. But perhaps there should be. •

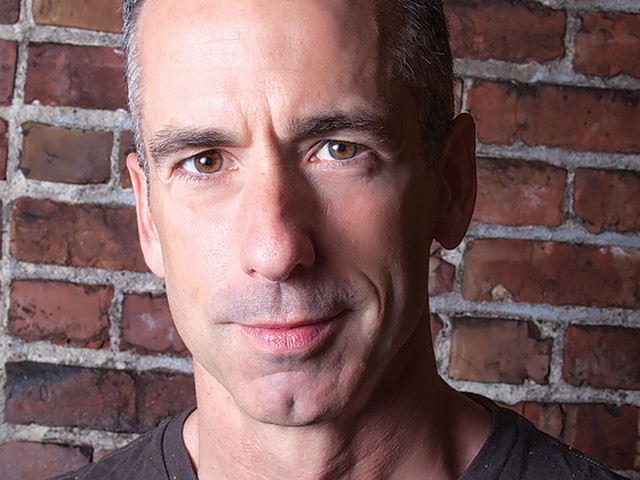

Dr. JoAnne Sweeny is a UofL law professor.