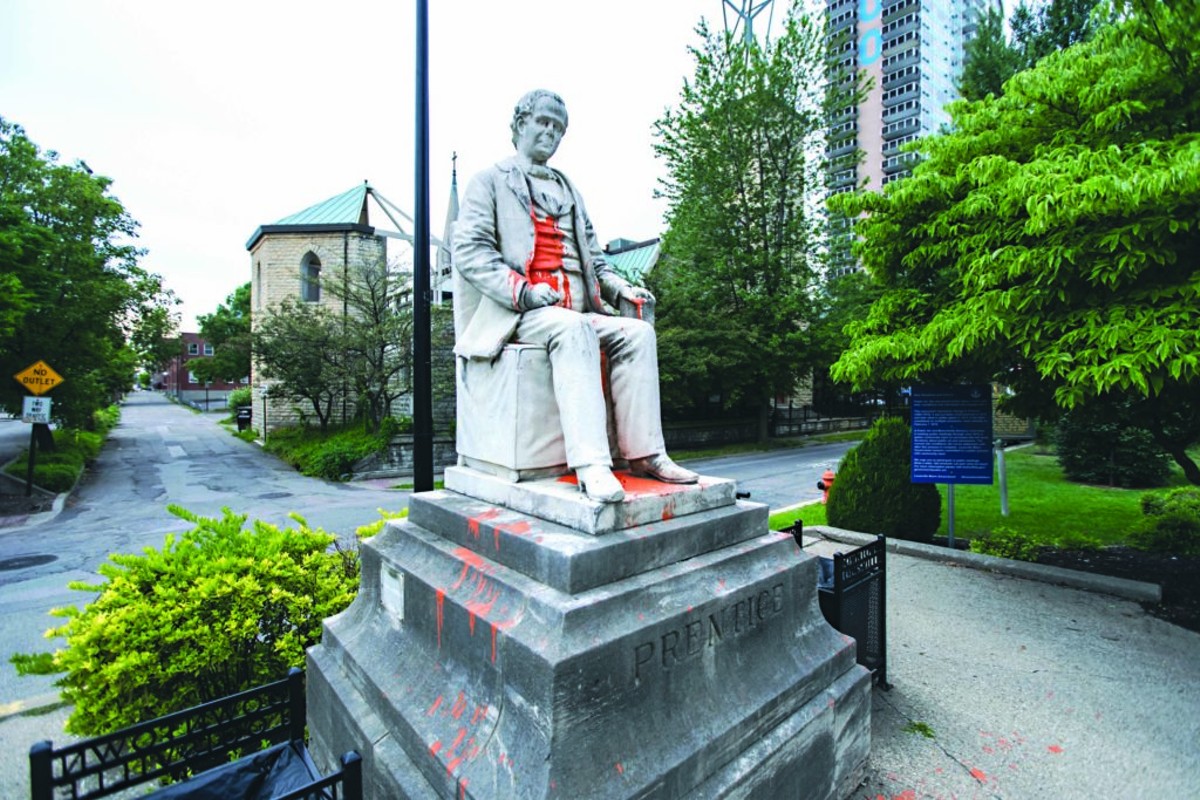

Just as we are seeing John B. Castleman in a new light because of new information about his past, we need to look at George D. Prentice the same way. The city wants to move the Castleman statue from Cherokee Triangle. It already put into storage the statue of Prentice, after decrying the 19th century journalist for what officials said were anti-immigrant writings that helped spawn the Bloody Monday riot Aug. 6, 1855.

But, as with Castleman, contemporary characterizations of Prentice are misinformed.

His statue needs to be returned to the Courier Journal, where it first sat until being moved to the Louisville Public Library in 1914, its last location.

The late historian Thomas D. Clark once declared in the Courier Journal that 19th century journalist Prentice had, “an enormous influence” on Kentucky history, American journalism and American political history. Yet, Clark said he could not decide whether Prentice was a “devil or angel” because Prentice supported the nativist “Know Nothing” party. If anything, Clark’s dilemma illustrates why Prentice, the influential editor of the Louisville Daily Journal, remains one of the most misunderstood figures in Kentucky history.

The Bloody Monday riot was a major tragedy in our city’s history. Both the “Know Nothings” (officially the Native American Party) and Louisville’s Irish and German citizens blamed each other for the bloodshed. However it was Benedict J. Webb, a Catholic journalist and historian, who declared in 1884 that Prentice was primarily responsible for the tragedy. Despite the fact that the majority of scholarship has since absolved Prentice of the charge, he has remained the chief scapegoat in Louisville’s historical memory.

One overlooked and uncomfortable factor in the controversy is simply this — long before America became a melting pot, Americans regarded the United States as a Protestant nation. Prentice belonged to the first generation of Americans to confront the changes wrought by mass immigration. Between 1840 and 1860, the nation “welcomed” 4.2 million immigrants, per Robert Remini’s “A Short History of the United States.” The majority were Irish and German Catholics.

This human tsunami coincided with a wave of nationalist and liberal revolutions that swept Europe after 1848. To Protestant Americans, revolutionaries like Giuseppe Garibaldi of Italy and Louis Kossuth of Hungary were heroic freedom fighters. To Pope Pius IX they were dangerous radicals who threatened the authority of both the Catholic Church and Europe’s repressive, traditional monarchy. The pontiff’s ultraconservative views were afterward reflected in his 1864 Syllabus of Errors, which condemned the separation of church and state, freedom of religion, freedom of speech and a free press. The Jesuits were his chief defenders and the then-controversial order, which had been expelled from several secular nations, condemned the rise of liberal nationalism.

It is therefore understandable that Kentucky’s Native American Party leaders, including prominent figures like U.S. Sen. John J. Crittenden, voiced their concerns over the “Catholic question.” Furthermore, the desertion of hundreds of Irish Catholic soldiers from the Army to the enemy during the Mexican-American War also had strengthened fears that Catholic immigrants placed loyalty to fellow Catholics above national loyalty.

A staunch Whig, Prentice came to regard the new organization as the only party that stood for the preservation of the Union. His controversial “Americans are you ready?” election day editorial was typical of past writings and reflected the journalistic jargon of the times. The anti-nativist Louisville Daily Courier termed Aug. 6 as “The Day of Battle.” The Courier also warned that if force was used to prevent them from voting, the Irish and Germans immigrants would not be held accountable for the bloodshed that might follow.

On Nov. 7, 1897, the Courier Journal’s lengthy account of Bloody Monday blamed the violence solely on Blanton Duncan, a Know Nothing campaign manager, and brutal mob leaders such as Hercules Walker, Phil Victor and John W. Tompkins. Furthermore, it should be noted that the violence was not all one-sided. Violent men on both sides had blood on their hands.

In reality, Prentice was appalled by the violence and risked his personal safety by joining Know Nothing city officials in saving lives and property. According to Archbishop John L. Spalding, Prentice publicly regretted his role in the riots. Benedict J. Webb later admitted that Prentice was not an anti-Catholic bigot but rather an overzealous political partisan. As historian Charles Duesner wrote in 1963, Prentice’s editorials “were a contributing factor” but “neither the only nor the most important factor in creating the riots.”

The recent controversy over Castleman and Prentice does not reflect the wrongs of the past but rather the ugly wrongs of today. All people of goodwill must speak out against today’s fear driven xenophobia. But we need to ask ourselves: How does the removal of the Prentice statue impact the nativism of our times? A nativism that now threatens the spirit of our melting pot nation.

Prentice’s brief connection with nativism was a blight on his career. But Prentice’s career lasted four decades, and he was primarily remembered as a man who helped save Kentucky for the Union. Ironically what was perhaps the only monument to a leading Kentucky Unionist has now been erased from the historical landscape.

If this was a victory for our “compassionate city,” it was a hollow, meaningless one. •

James M. Prichard is a local historian.