Principal Robert Earl Gunn Jr. told them to close the cafeteria doors. He’d already shooed out the television cameras and parents craning their necks for one last look on this historic day — the opening of the new W.E.B. DuBois Academy.

In their smiles and too-long jacket sleeves, crooked ties and untied shoelaces, with jitters and expectation: These were the 154. The inaugural class of 11- and 12-year-old boys whose stories Mr. Gunn would help shape, the ones he’s convinced will make history.

He stood before rows of lunch tables and addressed them without a microphone.

“You-all are now home in the W.E.B. DuBois Academy,” he shouted.

The tenderness in his voice belied his volume.

“Once you walk through those doors, things are going to change,” he said. “You are now ours, and we are now yours.”

They could count on two things every day, he told them: Reciting the school creed and hearing their principal say, “I love you.”

“If you’re not used to hearing that, if that makes you uncomfortable, I don’t care,” he said. “Because for a year, we have been able to plan this school just for you. And we want you to know that you’re loved.”

Leslye Harbin, an 11-year-old sitting near the front, had heard that part of his speech before, when Mr. Gunn was principal at Foster Traditional Academy. Leslye’s first memory of the man was his voice, not his face. It was serious coming through the loudspeaker during morning announcements.

“I knew someone outside my family cared for me,” he said. “When he said it, I knew he meant it because he said, ‘From the bottom of my heart, I love every single one of you.’”

The W.E.B. DuBois Academy in Louisville — only the fifth school of its type in the nation — has been two-and-a-half years in the making for Jefferson County Public Schools.

It was the brainchild of Dr. John Marshall, chief equity officer for the school district. He wanted to create an optional school for young boys of color with an Afrocentric and multicultural curriculum that’s imbued with values such as resilience, discipline and empathy.

Named after William Edward Burghardt DuBois, a civil rights activist, historian and one of the cofounders of the NAACP, it’s modeled after Carter G. Woodson Academy in Lexington. It began its inaugural year with 154 sixth-graders in August. Next year, seventh grade will be added; the following year, eighth grade. Marshall dreams of extending the academy through high school and creating a similar all-girls school.

He wants DuBois to be the model for the nation.

But before all that, Marshall knew DuBois would need a powerhouse principal to succeed. And Mr. Gunn was the only man for the job, he said. After meeting him, it’s clear why.

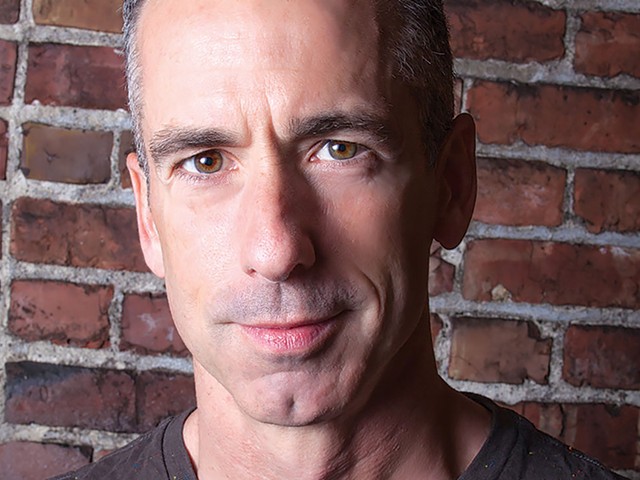

Mr. Gunn is unapologetic and unafraid to tell his own story. His fervor quickens as he talks about the 154. These boys become not them, but we. His preacher-teacher cadence confirms he’s one who has come not to convert unbelievers but to point young men to a mountaintop they can’t yet see.

“For far too long, it seems like, the group of young men in our building, the majority of them, have been left out, singled out, written off systemically,” he said. “Whether it’s the so-called achievement gap or the school to prison pipeline, there are so many barriers that have been set up. ...

“The legacy that I want to leave is showing that it’s possible for our young men to have the exact same opportunity as everyone else and that, if given that opportunity and support, they will go on to do great things.”

Mr. Gunn is the embodiment of what the school hopes to achieve: a young man of color who struggled but overcame. His story isn’t all that different from some he’s heard from the 154.

Neither of his parents graduated high school. His dad, Robert Earl Gunn Sr., worked at a factory for 42 years to raise his family up. Gunn Jr. struggled mightily in school. His sixth grade-report card was filled with Cs and Ds, he scored an 840 on the SAT, had to take remedial courses and, at one time, his college transcript showed he had a 1.9 GPA. But, he persevered and became both a teacher and a principal.

“I’m a real-life example of that kid in the classroom that some people can kind of write off,” Mr. Gunn said. “So as a principal, I carry that with me.”

But, he explained: “I don’t sympathize with a student. I can’t, because as soon as I feel sorry for you, I lower my expectations. You come to school, and you’re dirty? I’ll wash your face. Dirty clothes? I’ll change ‘em. You come to school, and you’re hungry? You’re gonna get fed. You come to school, and you’re mad, and those fists are balled up? I’m gonna hold your hands. I’m gonna tap you on your chest and tell you: ‘Whatever you’re going through, let’s talk about it.’ If we eliminate those barriers, what’s your excuse not to be successful?”

That’s why Mr. Gunn set no minimum requirements for admittance to DuBois. To apply, students had to say why they wanted to go. And parents had to express why they wanted their sons to attend.

That’s it.

All 52 students who applied from essentially the lowest-performing schools in the district were automatically in. Mr. Gunn wanted to smash any notion his school would cherry pick the best and brightest. There were 28 kids who scored Novice – the lowest – across the board and 28 who scored Advanced Program – the highest. The rest were in the middle.

But to Mr. Gunn, their numbers weren’t important. Their stories were.

Like the student who had a 0.4 GPA and had been suspended 28 days by Dec. 15. Mr. Gunn was moved by what his mother wrote: During a home invasion, he saw someone murder his father. “This school will save his life,” she said.

He’s in.

Another student, a twin, who had a high-performing sister who always seemed to outshine him. He’d yet to find his place in this world.

He’s in.

And Leslye Harbin, the young man at the front table in the cafeteria, who said he wanted to have Mr. Gunn as his principal again — and wear a sports coat. He likes the way a tie suits him.

He’s in.

Mr. Gunn heard so many stories like those. In one way or another, they were all like his, his father’s or those of the young men he grew up with. He knew if they’d had a place like DuBois, they’d have made different choices. And now these boys would, he was certain.

“Some make you laugh,” Mr. Gunn said. “Some make you get a little choked up. ... They’re all my sons. I will take care of them, and I will protect them, and I will fight for them like they’re my own.”

Even Mr. Gunn may not realize how closely these boys listen, how much they’re counting on him to keep his word, and just how much they expect of him.

For Leslye Harbin, it’s that he hopes Mr. Gunn will teach him to be a man: to be respectful of women, to be kind — to not be afraid of bugs. To be a surrogate father of sorts in the absence of his own.

Leslye’s dad has been in prison for complicity murder since Lesyle was just a year old. He’s visited a few times and keeps a photo of the man whose name he carries in his top dresser drawer.

In some ways, Leslye Harbin Sr. is an enigma — a hope-filled daydream of what could be or what might have been. Mr. Gunn, on the other hand, is an everyday man whose expectations he can meet and whose arms he can hold.

“He’s like a giant,” Leslye said of Mr. Gunn. “Say I get in trouble: He talks to me like a man. He tells me, ‘How am I supposed to get somewhere in life if I’m actin’ a fool’ and stuff?”

• • •

Down the main hallway at the DuBois Academy, banners extol the school’s PRIDE values: perseverance, resilience, initiative, discipline and empathy. Bright prints of high-profile historical figures line the halls. A banner with an African proverb hangs in the stairwell for these students — young lions as they’re called — to ponder: “Only when lions have historians will hunters cease being heroes.”

But the school is much more than its trappings. Mr. Gunn and his staff have made sure of that, starting with its curriculum, which they developed over the summer.

The optional school has an Afrocentric curriculum, but it’s not segregated. There are seven white students, four Latinos and one Asian. But the lessons are different. They’re taught through an Afrocentric or multicultural lens that’s focused on community as opposed to a Eurocentric one with an emphasis on the individual. The lessons include more black history but not just in history class. Also, in science and math and reading. Coursework might integrate hip-hop culture in a poetry lesson or Colin Kaepernick in the study of hero archetypes.

The idea is to create an environment in which these young boys feel comfortable, relaxed and safe because they see others who look like them and have classmates with similar experiences.

Jessica Dueñas, a DuBois Academy teacher, explained it this way: “If you feel good about yourself, if you feel safe in your classroom, you’re going to be open to learning. It’s a research-based idea. Relationships matter first. Once you’ve got the relationship down, everything else opens up. Maybe they’ll go from Novice to Apprentice. They might not jump to Distinguished. But that’s not the goal. … In terms of the social piece, I want these young men to come in and value themselves enough that when they go back into their neighborhoods they’re making good decisions because, hey, maybe they will disappoint someone in the building if they found out they did something foolish outside.”

That’s why every piece of the curriculum has a PRIDE component attached to it. And teachers will assess students on those skills. What does perseverance look like in this science project? What does empathy look like in this history lesson? Students must not just define it but demonstrate it in a community project.

“Numeracy, literacy — they’re all common core subjects,” Mr. Gunn explained. “They’re very important. But when I talk to parents about what they want for their sons — we’re raising young lions, and we turn them into kings. I haven’t heard a parent tell me they want their son to be Distinguished on KPREP or Proficient on KPREP.

“I hear that they want their sons to be better leaders, better learners, better fathers, better husbands, better brothers, better partners. So, what are we going to do to make sure we have those things? What do we want our students to look like at the end of the process? [Teachers are] never going to hear me say, ‘Hey, get those test scores up.’ [They] might hear me say: ‘We need to get this young man’s spirit up. It’s kind of broken right now.’ So, the big picture is: We want to do education differently. I think the purpose of education is to make young people better older people. So, when it’s time to take care of us and take over this world, they have the skill set, the mindset and the capacity to do that. That’s what we’re offering at DuBois.”

• • •

Mr. Gunn knows the dominant discourse, the narrative that says young boys of color aren’t assets in the community; they’re drains. And he knows that to change the notion, his staff will have to teach the 154 not just prowess with a pen — but the power — to tell their own stories.

And that starts where each one of theirs begins.

For Leslye Harbin, it’s in Louisville’s West End, born to a 15-year-old mom. His dad went to prison after Leslye turned a year old.

Now 12, he has a baby face, still, with a prominent scar on his forehead from a 10-speed bike accident when he was 5. He’s tenderhearted and jabbers on about toy cars in his basement one minute and the next, a news story about a 15-year-old who was stabbed to death and left this world without knowing why. He’d rather work math problems in the air-conditioned house than play outside in the heat. He’s a sharp dresser, got baptized at West Broadway Church of Christ and fully believes dogs are his kryptonite, especially one he calls the hotdog-dog that lives in the same alley where a man was shot.

He hears, “I love you” plenty at home. From his mom, his Grammy, his uncles. But it bothers Leslye that he doesn’t hear it often from his dad. He’s in prison in Western Kentucky.

“If I had him around I’d be a happy kid, normal, satisfied,” he said. “A normal kid playing sports and doing things like fishing and stuff.”

He doesn’t talk to friends much about his dad.

“If somebody asks me, ‘Where’s your dad at? I need to speak to him.’ I’m like, ‘He’s not around at the moment.’

If they ask where he is, sometimes Leslye just says he’s at work.

“I feel like if I tell people they’ll be like oh, oh and telling other people and spreading it out. For me, it’s a bad thing to know. Nobody should be in jail. They should be in jail for the bad things they do, but they shouldn’t have did it.”

Leslye is his mother Antwanette Chillers’ eldest child and her only son. He never wants to disappoint her.

He knows about his mother’s teenage past, the gang she was in called Bad News. They weren’t into drugs, but they fought, and the young men carried guns. He sees guns in his neighborhood, too. He’s cautious on his way to the corner store, as sirens wail past on Broadway and when he overhears men talking about what they’ve seen in the alley: Gimme the money! Gimme the money! Pow!

He can’t walk more than two blocks from his house in any direction alone. He runs to the middle of the house if the gunfire is close.

“I’m worried about disappointing my mom because she didn’t get to go to college,” he said. “I think if I go to college like my cousin she will be happy for me.”

It’s clear he’s listened in earnest to her admonitions because he repeats them in singsong.

“Arguments lead to fights. Fights lead to guns. And guns lead to death,” he said.

Leslye has moved from house to apartment to house again in his young life because the family outgrew one place, or the landlord didn’t make repairs on another. That meant he moved schools, too. Maupin. McFerran. Roosevelt-Perry.

Before Foster, he was out of control. Classmates bullied him just to see him explode. He felt ignored by teachers. And by then, his mother had another baby, his middle sister, and she didn’t have as much time to spend with him.

Finally, his mother got him into Foster where Mr. Gunn was principal, and he flourished. Leslye calls Mr. Gunn his school parent.

“Leslye hasn’t had a bad year since I met that man,” Antwanette said. “I’m blessed and thankful for him.”

So, when Antwanette found out Mr. Gunn moved to DuBois, she wanted Leslye to attend. With the uniforms and the creed, she thought the school might be like a “mini Trinity.” Then she read more about the curriculum.

It was more than she’d ever hoped.

• • •

Days before the start of school, all 154 boys stood in the Muhammad Ali Center for the first time in their uniforms for the DuBois Academy’s inaugural coat and tie ceremony.

They walked down the center aisle to the voice of John Legend, singing.

“One day when the glory comes … It will be ours, it will be ours.”

City dignitaries. A poet. A violinist. An NBA star. They took the stage to pledge support for the 154.

The superintendent talked about success being on their shoulders. Mr. Gunn, of making history.

There were tears and ties, pledges and prayers.

“When we talk about numbers, we leave out names,” Mr. Gunn shouted. “When we leave out names we forget about the stories. And best believe each and every one of these young lions has a story that he will be empowered to tell.”

The mic cut out, but Mr. Gunn kept going.

“We are going to change the narrative. We are going to push back, because every single young man will be exactly what he wants to be, not what anybody tells him he needs to be.”

• • •

On Aug. 15, the real work of the DuBois Academy message began.

The first few weeks were tougher than Mr. Gunn expected. For Leslye, too.

Mr. Gunn said he felt like he’d been knocked down in a prize fight.

Leslye was already in detention by the second week of class. But his first progress report showed he’d earned all As and Bs.

Mr. Gunn sat in the principal’s office on the floor with Leslye because his office furniture hadn’t been delivered yet. Some classmates swiped his pencils and notebook. He didn’t know who, got mad about it and wouldn’t leave the classroom once the bell rang.

It was a small teaching moment about perseverance, about resilience.

But by Leslye’s second report card, his grades dropped to three Cs, a D and a U. The U means unsatisfactory, and it’s the lowest mark. He was suspended for two days for fighting. But, he also joined student council and an after-school club where students sample international food.

Leslye was disappointed in his behavior.

“I don’t need nothin’,” he said, hanging his head. “I need to control myself. I need to use my mind and think more, think before I do.”

But he isn’t giving up. And neither is Mr. Gunn.

“I’ve yet to meet a student that I’ve worked with over the course of 16, 17 years that was unable to meet my expectations,” Mr. Gunn said. “You just have to be relentless and unwavering in that commitment to them to see in them what they may not see in themselves.”

High expectations with love.

Teachers frame their classes with these tenets every day and point to behavior that exhibits those values.

Thank you for taking correction, Mr. Williams. That’s how we show perseverance, Mr. Harbin. Gentlemen, let’s show some empathy here.

Language arts teacher Mary Leslie explained it this way:

“We want them to understand you don’t have to defend yourself here,” she said. “You’re not trying to prove anything to anybody. You are here to learn and to grow. And for some of the kids, it’s like, ‘I’ve got to keep proving myself. I’ve gotta show myself tough. I’ve gotta show myself as not being weak. I’ve gotta prove to you that I have whatever it is.’ And they’ve gotten so accustomed to having to do that. And that’s what we’re trying to get rid of here.

“You can come in, be who you are and let’s grow from there.”

• • •

Every Friday morning, all 154 boys gather in the cafeteria before class starts for Pride Brotherhood time.

They recite the creed in call and response. And then shout: One Pride! One Brotherhood!

But it’s what comes next that sometimes moves these boys, their teachers and Mr. Gunn to tears.

It’s a segment called showin’ some love.

Mr. Gunn hits play on a boom box and soul singer Bill Withers’ original “Lean on Me” blares through the speakers.

They have two minutes to show love to their brothers. To teachers. To Mr. Gunn.

“We hug people and shake their hands,” Lesyle said. “I think it’s beautiful because we get to uplift people. We never did this in any other school. Some boys don’t hug each other, but if you get close to Mr. Gunn, he’s gonna hug you. He calls himself the big teddy bear. My friends, we shake hands and pat each other on the back.”

But that’s not all. Any boy who wants to, stands up and recognizes his classmate by name in front of the 154.

For helping me with math homework.

For not giving up.

For being my friend.

DuBois Academy is a place where the 154 will be loved, Mr. Gunn said.

They were chosen to be there, he said, and they’ll write their stories despite what the world may say about them.

By not just talking about love but showing it. •