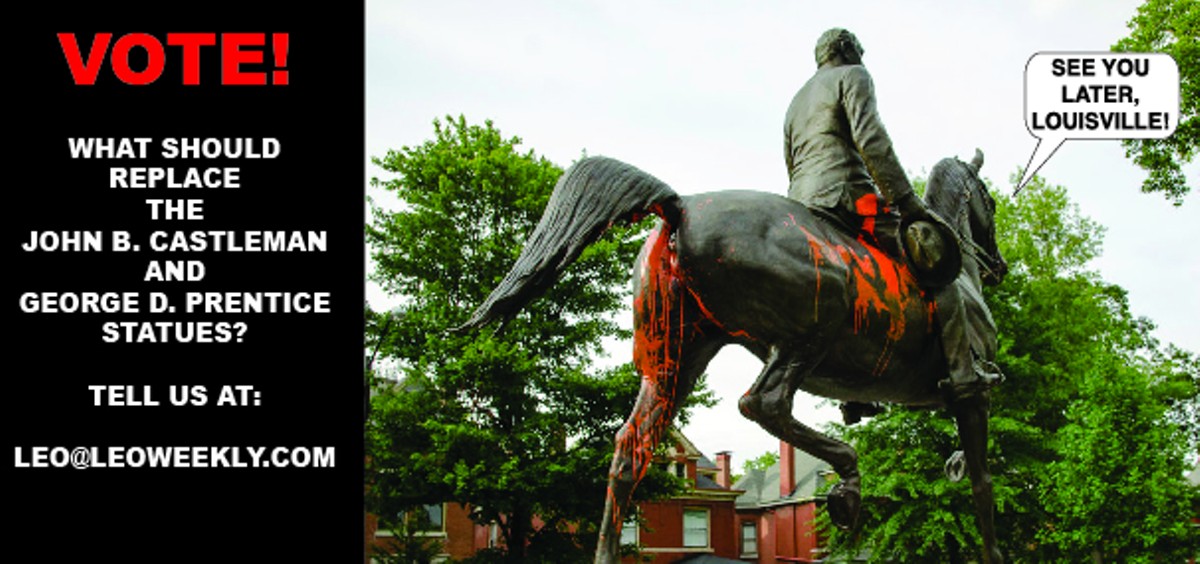

When Roger Porter heard about the recent decision by Mayor Greg Fischer to remove the controversial John B. Castleman statue from the roundabout just outside of his Highland’s condo, the 45-year-old had one question:

What will replace it?

“I really hate seeing the horse go. I like the concept of it. To see it empty, we’re not too happy with that,” Porter said this week from his job at Highland Mart.

Porter asks a question that has yet to be answered not just in Louisville, but in cities across the nation as they attempt to fill the empty spots left open by the removal of Confederacy-related monuments. Castleman’s statue in the Cherokee Triangle is being removed because of his role in the Confederacy, and the one of George D. Prentice, behind the downtown library, is being taken down because he was an anti-immigrant newspaper publisher who, some say, stoked the Bloody Monday riots here 163 years ago.

No alternatives have been offered to fill their voids.

The Mayor’s Office declined to comment, referring questions to a press release, which said no plans had been discussed for replacements, but, when they are, they will be reviewed under guidelines from the Public Art and Monuments Advisory Committee and the Commission on Public Art. These include the aim to display artwork that increases “the diversity and plurality of figures and histories depicted,” as well as to “educate our residents and our visitors in an honorable but also honest way.”

More than 32 memorials have been removed nationwide, most in the aftermath of the deadly Charlottesville, Virginia, rally a year ago. That gathering had been organized under the guise of protesting the planned removal of a Robert E. Lee statue. Due to ongoing litigation, it still stands. In fact, few of the statues at the centers of these controversies have been replaced.

Activists in Baltimore erected their own folk-art sculpture on pedestal that had held a statue of Confederate Gens. Stonewall Jackson and Robert E. Lee. The papier-mâché piece was vandalized and ruined by the weather just days after going up. In March, officials rededicated this portion of the park Harriet Tubman Grove in honor of the famed abolitionist leader. But the base where the generals on horseback stood remains barren.

Contentious sculptures in the U.S. Capitol’s Statutory Hall have had seemingly faster replacement results. In 2009, Alabama’s memorial to Confederate soldier Jabez Curry was replaced with a statue of Helen Keller. Earlier this year, Florida switched out their sculpture of Confederate Gen. Edmund Kirby Smith with one memorializing civil rights activist Mary McLeod Bethune.

What do Louisvillians think should go in the stead of these statues?

Louisville loves its hometown heroes, so proposals might start with Muhammad Ali. But Islamic law, generally, bars three-dimensional depictions of Muslims.

Phillip Golbsborough, 58, has lived near the Castleman statue since 1964. While he doesn’t agree with removing the statue, if it’s going to happen, he said, he’d like a fountain built in the space.

“You just can’t go around tearing things down to please other people who think these things offend them,” said Golbsborough, while working at a food truck on Bardstown Road. “If they’re easily offended of that nature, then, shit, you’ve got a lot to learn, because I’m going to offend you more than that guy on the statue. And I’m alive.”

His customer, Highland’s resident Todd Bartlett, suggested famed African-American jockey Jimmy Winkfield be considered. “He was the greatest black jockey of his time,” the 59-year-old said.

Down the street, 34-year-old Andrea Tindall, said inclusivity and utility must be considered. For instance, she said, she once saw artwork that consisted of rainbow painted bars, forming an awning under which people could sit. “That’s useful. I like useful,” Tindall added. “It would bring everyone together. I mean, we do Pride here. So why not?”

Sitting on the steps of St. James Church on Bardstown Road, a group of 20-somethings was enjoying a discussion under the shade. When asked, 22-year-old Community Engagement Coordinator Sarah Rohleder proposed not sculpting a living person so there is less opportunity to “screw up.” Underrepresented populations should also be considered, she said.

Her friend Ben Schroering, 24, doesn’t believe a person should be depicted. It should be a representation of the city, perhaps a re-imagined fleur-de-lis, he said. “Given the encroaching march of time, we are constantly going to be disappointed with any person that we put on that spot,” Schroering said. “Symbols can change with the times.”

Nature was the focus of 24-year-old Quincy Nelson’s idea —perhaps a solarium or field create a place to meet. “I don’t want another statue. I’m getting tired of old, dead people,” Nelson said.

Across the road, friends May Hale, 27 and Keiana Petty, 27, want a positive message. Their concepts veered more toward Louisville standards such as Derby winning horses and bourbon manufacturers. “Do something everybody likes, instead of having to debate about everything all the time,” Petty said. “Let’s leave the disputes alone and just put something that everybody would go, ‘Oh, wow.’”