[Editor's Note: The following is an article about storytelling culture around Louisville. Read a story by Birds Of A Feather co-host Randi Skaggs here]

On stage is David Serchuk. In person he can be a quiet guy, soft spoken with a sweet and kind-of-dorky laugh. But when he’s on stage, his personality gets amplified, and his playful energy is turned up to 10 without ever taking away from his air of compassionate humanity. When he’s joking and telling stories about how strange and upsetting life can be, he’s inviting you to laugh with him, and you to empathize with his pain, and possibly remember some tough times in your own life.

Tonight, he’s wearing a turkey suit.

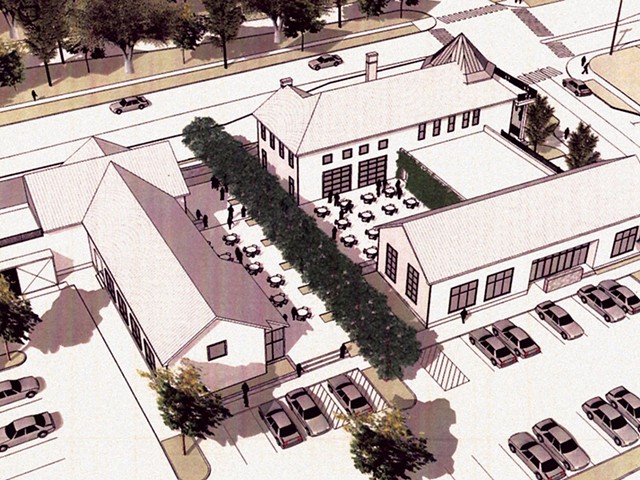

The 45-year-old freelance journalist is welcoming the audience to The Bard’s Town, cracking jokes about his outfit, and warming up the crowd.

Great to see you all, and let me tell you about the format of the show. We have two themes! One is Birds Of A Feather and that’s going to go first, and the second is Flying Solo, after an intermission.

Next to him is Randi Skaggs, 41, his coproducer and cohost, and also his wife and co-parent. During the day, she’s a school teacher, but tonight she dressed in an outlandish fighter pilot outfit. She’s also someone I’ve seen on stage multiple times. She brings a sort of merry twinkle to the stories she tells, but always drives them home with a finish that feels profound, yet humble. She also cracks a few jokes about Serchuk’s outfit, warming up the crowd for what comes next.

Welcome to Double-Edged Stories’ second show ever! I think everyone has a seat tonight, which is kind of crazy, because last time we had people crouching by the bathroom, which is not conducive to story listening.

They just seem like regular people, who happen to be on stage, telling stories.

They are both regulars, and regular winners, of Louisville’s Moth Story Slam. But on stage tonight, they are telling different kinds of tales, as they present Double-Edged Stories, a new storytelling event, with a unique hook and structure.

Instead of a single theme, there are dueling ideas. Tonight it’s “Birds of Feather, and Flying Solo,” information, which, when combined with their senses of humor, explains the costumes.

Double-Edged Stories is one of several storytelling events that have opened in town in the years since The Moth StorySLAM came to Louisville. What started as a single monthly event at Headliners Music Hall, is emerging as a full-blown storytelling culture. Stories get told in bars, basements and theaters, in venues small enough that only a dozen people can attend, and then all the way up to the 500-seat Bomhard Theater in The Kentucky Center.

It’s a loose community — some storytellers jump from event to event, while others show up once, tell that one story they need to get off their chest, and are never heard from again.

Those who stick around, on stage and in the audience, often form tight bonds of love and friendship. It’s hard not to when you’re sharing some of the most intimate and personal details of your life.

The Moth’s Metamorphosis

The Moth’s earliest stage was on a Georgia porch, where moths would circle the porch light, and occasionally crawl through holes in Moth founder George Dawes Green’s screen door, while he and his friends shared stories. Green moved to New York City and brought The Moth with him, starting shows in 1997, and while it’s grown and spread, it’s still pretty much shaped the same way that it was in the beginning.It’s a story slam during which 10 people each get five minutes to lay a story on the audience. Each performer gets a score, and a winner is declared. The performers are drawn from the audience. Any person interested in telling a story puts their name in a hat, and 10 names are chosen at random.

The New York show grew in popularity, partially because of “The Moth Radio Hour,” a radio show and podcast that draws the most compelling storytellers from the on-stage performances, and broadcasts them. The show also features stories from The Moth’s Mainstage, where tellers can take up to 15 minutes to get their stories across, without the competitive aspect.

Jenifer Hixson, a senior producer with The Moth’s national organization, said that what The Moth does is present storytelling at its simplest. While films, plays, ballets and even some visual art use some storytelling, The Moth strips away the bells and whistles.

“It’s just the plain old thing, a single person talking alone into a microphone,” Hixson said.

Before too long, satellite Moths started appearing in other cities. Often they were being run by people who had performed at one of the Moths in New York.

Tara Anderson is one of those folks, having moved to Louisville after living in the Big Apple for several years. She works for WFPL during the day, but, in 2011, she brought The Moth to Louisville. It has steadily grown in popularity, but it was a small group at first.

“We had people who had told stories at The Moth before in other cities, we had a few people that came from the poetry slam scene in Louisville, a lot of writers, some actors, some comedians,” Anderson said. “Anybody who wanted to get up on stage.”

That group also included people who had just heard The Moth on the radio.

Due to The Moth’s national success, other storytelling shows started emerging, first in New York, and then in other cities. The Moth producers in New York didn’t mind, even though a few of the early examples in Louisville were pretty derivative.

“I think one even had another insect name,” recalled Anderson.

While Louisville’s first string of imitators have dropped away, several other storyteller shows have been established, offering different formats that bring out different kinds of stories.

We Still Like You

On a recent Tuesday, Shelley Hoblit was finishing a story in the basement of the Market Street restaurant Decca. The 26-year-old comedian talked about a the gut-wrenching, yet darkly-hilarious time that she was temporarily locked up at Our Lady of Peace psychiatric hospital. She looked shaken just from telling the story.Then MC and coproducer of the event, Chris Vititoe, got up on stage and led the audience in a chorus as we all yelled: “We still like you.”

On-stage storytelling sort of implicitly suggests that there may be something of confession and absolution in the telling of a tale.

But We Still Like You makes that absolution official with a call and response that shares the name of the storytelling event and podcast. Like The Moth, it’s a satellite of another show, a Chicago-based group of the same name. Louisville’s version got started with Vititoe considering the comedic value of storytelling, while at the same time Mandee McKelvey, another Louisville comedian, told a story at We Still Like You in Chicago. The serendipity is, Vititoe had already decided to approach McKelvey as a possible cohost for a new show.

“She had just gotten back from Chicago, and she got last-minute booked to tell a story at We Still Like You and she had an amazing time,” Vititoe said. “So, as I’m telling her I wanted to do a storytelling show, and I thought she’d be good to partner, she’s telling me about that show.”

We Still Like You is a corner of the scene where comedy and storytelling overlap. Not only are Vititoe and McKelvey both stand-up comics, most of the storytellers in the show are comedians, though it’s not a hard-and-fast rule.

Vititoe likes what happens when the two art forms overlap.

“What happens is we ask them to tell a story that isn’t necessarily funny, and when they tell a serious story, their sense of humor comes out in a completely different way, than it would if they were writing a joke,” Vititoe said. “It comes out in a way that is exciting and natural.”

Instead of monthly themes, the show has a general guideline: Stories have to address something you regret, or expose a time you were ashamed. For an extra dash of personality, We Still Like you also features an artist, who creates a painting illustrating some part of the story in real time, during the same 10 minutes the storyteller has.

While this show frequently gives comedians their first taste of storytelling, for Hoblit, whose story about that aforementioned brush with mental health institutionalization, it was kind of the reverse. It was also one of the best stories I’ve heard.

“I had been doing a couple of The Moth story events, and I did a couple of those, and while I was on stage there, I realized I more enjoyed the actual wanting to make people laugh more than the storytelling part,” Hoblit said.

Hoblit is 26 and working in advertising, and, like a lot of first time storytellers, or in this case nascent comedians, she started by listening to The Moth’s podcast. “Then I went to one of the live events, and it was really neat and I thought I could try it myself,” said Hoblit.

Since that first time, she’s told lots of stories, and performed in a lot of comedy shows. Her stand-up is still pretty story-centric, though she’s learned to add in what she calls “smaller punch lines” in the context of her stories.

But at We Still Like You, despite the humor she managed to inject, she had a serious agenda: “That one was more of a, ‘this is a great chance to get the story off my chest,’” she said.

More Space for Stories

Skaggs and Serchuk were some of the first storytellers at Louisville’s Moth.They met in New York’s improv scene, specifically, hanging out and improvising with the group surrounding The Upright Citizens Brigade. Serchuk even ran a storytelling night every two months, though it was more geared toward writers telling stories they had written. Eventually, the two moved back to Louisville.

They had both told stories at The Moth in New York, and they were excited when Louisville’s Moth started up.

As it grew in popularity, individual storytellers got to tell stories less and less. Toward the beginning, the hat would only have six or seven names in it, now it frequently has 30.

So part of the reason that Skaggs and Serchuk decided to create Double-Edged Stories was that they wanted to tell more stories. They also wanted to give other people the chance to tell more stories. They felt there was a greater need for stage time than The Moth alone could supply.

“We wanted to give people more opportunity,” said Serchuk. “We’ve known people that go five months in a row and don’t get called.”

Double Edged doesn’t have a hat. Storytellers submit a pitch for their story, and Skaggs and Serchuk curate. Even so, some of performers are newbies, in addition to more experienced storytellers.

“I think there’s a different nature to a curated show,” Skaggs said. “We picked out what we know are great stories. There’s no judging, we’ve taken that element out, so I think there’s a very different feeling.”

Double-Edged features longer stories, something that happens on the Moth’s Mainstage in New York, but not here. Those longer stories can go in depth in ways shorter stories can’t. Sometimes with a short story you can tell it’s actually a much longer version compressed, and Skaggs said she wants to hear good stories in their entirety.

Serchuk added that Double-Edged Stories needed to justify existing by finding these differences between itself and The Moth.

“We always wanted two themes, because we didn’t want to be a low-grade knock off of something great,” Serchuk said. “We wanted it to be fun and different. A different experience for people who want to hear stories.”

The proliferation of storytelling events suggests that Serchuk and Skaggs are right — Louisville has more stories to tell.

While it’s already one of my favorites, Double-Edged Stories has been around for only a couple months. We Still Like You has been sharing Louisville shame for about a year. Last year, a traveling show out of Los Angeles called Expressing Motherhood came to town and recruited local moms to share the stage. Last month, frequent Moth winner Graham Shelby premiered a one-person show at The Kentucky Center built entirely out of his stories. The Mothra, another comedian-centric story show, is a gift of the febrile stew of yucks that can be found at Kaiju. And I’d be willing to bet there will be more stories, in other venues soon.

While it’s impossible to know exactly why storytelling is spreading its wings, it is clear that it is, at least in part, because we all have a story to tell, and we were just waiting for space at the mic.

Hoblit is now a seasoned performer, but not too long ago she was just another member of the audience. She believes that inclusivity is the growth serum juicing up the scene, though she uses another word to describe the mix of amateurs and pros who are getting up on stage.

“I think it’s really inspirational, to make people feel like they have something to say, that people would want to listen to,” Hoblit said. “It’s a lot less exclusive than like, comedy or acting, so it allows for a much more community based… I wanna say ‘organism?’” •

The Moth in Louisville is on stage at Headliners Music Hall the last Tuesday of every month. You can put your name in the hat there. Go to themoth.org for more information. We Still Like You is in Decca’s basement on the last Thursday of every month. The next Double-Edged Stories will be at The Bard’s Town on Jan. 6, and you can pitch a story for its“Begin the Begin and Closing Time”until Dec. 10. Search Facebook for “Double-Edged Stories” for more information.

"Wonders" a story by Randi Skaggs

He leaned over to pick something up. It was a pan. My boyfriend picked up a frying pan from the sidewalk in Brooklyn. “I need a pan,” he said.Typical Dave. Jump in head first, never consider the risks. Who’d owned that pan? A serial killer who used it to fry human brains? How long had it been out on the sidewalk? Long enough for a dog to piss on it?

I mentioned these concerns to him, and he replied, “I’ll wash it.”

It was well after midnight, and we were headed back to Manhattan after a party. Suddenly, we heard a voice behind us pipe up. “Hey, nice pan!”

It was a tall, thin, elderly gentleman. He was wearing a tweed suit, frayed in several places. There was a large, blue ink stain on the lapel.

I went into defensive mode. I’d lived in New York long enough to know that I needed to be ready to either bolt, or punch him in the nuts.

Dave went the opposite direction. Dave engaged.

“Right? It’s a perfectly good pan, and I need one.”

Dave was born and raised in the New York City metro area. I was born and raised in a tiny town in rural Kentucky, and yet I felt I constantly had to teach him about the dangers of the world.

The man motioned toward the arch at Grand Army. “Did you know this is one of the largest and grandest arches in the world? Notice how those horses on the crowning statue have no reins.”

He was right. There were no reins.

I bolted toward the subway station. Our new friend kept pace. He swiped his card, followed us to the platform for the Manhattan-bound train and, of course, he sat with us.

Then, the man’s demeanor became almost urgent. “You simply must come see my collection. At my firm, I have an incredible collection of subway maps from all over the world. It’s marvelous, really.”

“Maybe,” Dave said.

“Now! You don’t want to miss it. I’m heading to the office anyway!”

Just as I was getting ready to rudely shout, “No Thank You,” I heard Dave said, “OK. Why not?”

You see, this was back when our relationship was new. Back when he didn’t know he had to run everything past me first.

So, here we were. Following a strange man to a more deserted location.

The financial district is a ghost town at night. We were all alone. We arrived at the base of a skyscraper, and he implored us to look up. “This is art deco at its finest.”

He pressed a button, a buzzer went off, and we walked into a grand lobby.

He showed us the intricate tile work of the lobby, which he said was based on Aztec designs. Then he pushed the elevator button, and up we went, to the 35th floor.

We emerged into a luxe law office. The walls were dripping with art. Audubon prints from the 1950s, an ancient Roman tapestry. We went into a tiny, windowless conference room. He began to show us subway maps.

There were more subway maps than I could have imagined. From the tangled web of the Paris Metro to the clean lines of the Washington, D.C. subway. He showed us a map of Tokyo’s system, which he said was presented to him at a traditional tea ceremony.

Then, “I must show you my article! They did an article on me!”

He swiftly left the room, and shut (locked?) the door behind him.

And for the first time this whole night, Dave looked scared.

“What the hell?” he said. “What are we doing here?”

“I don’t know,” I said, happy he was finally waking up.

“We don’t know who this guy is at all! Listen,” he said. “I still have this pan. If he does anything, I’ll hit him in the head with it.”

And although my boyfriend was talking about striking an elderly man in the head with a frying pan, I’d never found him sexier.

The man came back, carrying a newspaper clipping. It was from The New York Times, about 10 years old. It had a picture of him, in a much cleaner suit. It said he was a big-deal lawyer with a collection of art worth millions.

And that was that. It was very late at this point, so we offered to walk him back to the subway. He said he needed to stay and do some work, that he didn’t really sleep so well these days.

Dave and I didn’t say anything, but we both had tears in our eyes. What a night! And if I hadn’t been with Dave, I would have missed it all. All the wonders of Bob’s office, Bob himself, a man I pigeonholed in four seconds flat, a millionaire who wanted to show two strangers on the street some of his treasures.

Dave still shows me the wonders around me, helping me to stop viewing this world as a war zone filled with dangers, rather a wonderland to be explored. •