Without warning, Stephanie Gillis whips out a can of Fancy Feast and walks down a narrow road lined by trailer homes. She snaps it open and pushes down on the metal top. Liquid slowly spills out, leaving a trail back to where we are stationed in the bright white Alley Cat Advocates van. While the van is air conditioned, it’s up in the 90s tonight, and she apologizes for sweating.

The work she is doing requires cat-like qualities: speed, strength, smarts and agility — all of which she has.

Her goal: capturing five stray cats so they can be transported to the Snip Clinic to be spayed or neutered.

Gillis sets up three traps. Two small ones have newspaper on the bottom, and she smears cat food at the entrance and middle and leaves an ample amount at the back. She places those strategically on the property. The last trap she sets up is her favorite. It’s a box trap, a large device about three feet square, and she sets it up on the homeowner’s front porch. This trap can capture several cats at a time. She tells me it’s like the trap Elmer Fudd set for Bugs Bunny in the old Looney Tunes cartoons. A single tug on a string and blam!

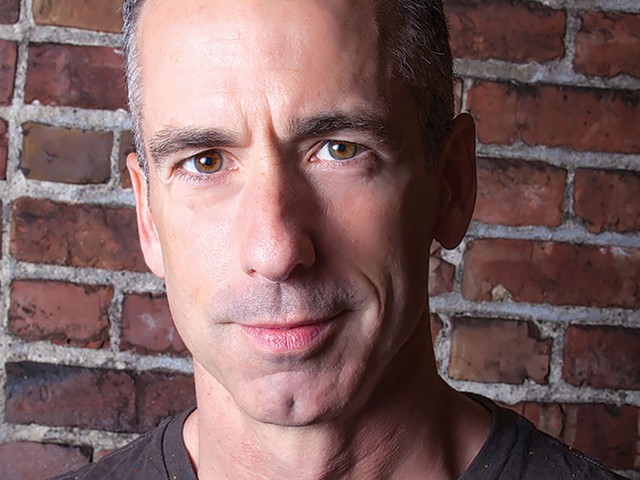

Gillis, 36, is the cat care coordinator for Alley Cat Advocates and one of the nonprofit’s three full-time employees. Her job is to help people in the community who care for the cats, but wouldn’t be able to capture and transport them alone — often people who are older, disabled or have limited financial resources. She goes out to trap cats about three times a week. The rest of her time is spent making appointments for those in the community who are able to trap and for volunteers who help folks who aren’t able to trap. She answers questions, offers advice and doles out encouragement about Trap-Neuter-Release, or TNR. Gillis estimates that between the trapping Alley Cat Advocates does and including the traps that are lent out, about 150 cats are trapped a week.

While Gillis doesn’t own a cat (she has three dogs), but she is no stranger to them.

“I fostered a cat. It was a very long foster, about three years,” said Gillis. “And now that cat lives with my partner’s mom.”

She spends much of her time among cats — and people — facing difficult circumstances and struggling to get by. And she learns a lot about caring from both the animals and the humans.

Some days can be very rough, like one she recalled for me.

“We got in a bunch of sick cats and a couple of the little baby kittens didn’t make it,” said Gillis. “But that same day, we spayed and neutered 43 cats safely, so there seems to be more good than bad, but you can’t help but feel that it is a little hopeless at times.”

The Life of a Community Cat

Today, Gillis is helping Lou Felty. The 80-year-old resident of Preston Village has been feeding community cats for the five years she’s lived here. She called Alley Cat Advocates for help getting them fixed.Preston Village mobile home park is close to Preston Highway, near several fast-foot restaurants, a Wal-Mart and Kroger. Cats wander through this leafy neighborhood of closely-spaced homes, sometimes stopping at Felty’s white single wide, on which a dark wood plank is attached with FELTY spelled out in large white letters.

Felty tells us she has been an amateur fencer for the past 50 years. Her white T-shirt is adorned with a yellow fleur-de-lis with fencing foils crossing through the center. She wears a dark baseball cap with a large and sparkly silver, red, white and blue American flag in the front. She smiles as she watches Gillis take the traps out of the back of the van.

Felty didn’t name the cats, but she knows each of them. She says that many have long fur and are really pretty, but they won’t let her pet them. She tells us that she believes she is the only one in the community who is feeding them. This is something that Karen Little, executive director of Alley Cat Advocates, said isn’t likely.

“The cats that live outside. They also have homes,” said Little. “They don’t have a home that you traditionally think of like indoor cats, but they have a home. They know that tonight, I will sleep under this deck, and on the warmer nights, I will sleep in the shed, and I eat at these six places, and people pet me to the extent that I want to be petted, and sometimes I lounge on this lounge furniture.”

Aside from reducing the cat population, spaying and neutering also cuts down on undesirable cat behaviors such as spraying and crying out when they are in heat. And spayed or neutered cats typically have a better temperament.

Not everyone in the community appreciates this.

Andrew Melnykovych is vice president of the Beckham Bird Club. “The ecologists who have studied this have looked at trap-neuter-release and it is not a solution,” said Melnykovych. “Because it puts feral cats back out into the environment to do what feral cats do. They are killing birds and small mammals in large numbers and the ubiquity of the toxoplasmosis parasite in the environment is tied to high populations of feral cats as well.”

Melnykovych believes the ultimate solution is not to have outdoor cats. This, he said, would be better for the cats and better for the environment.

“How you get there is obviously very controversial,” said Melynkovych. “If you don’t release them, then what do you do with them? The tragedy of the thing is that a lot of the feral cats are not going to be adoptable.”

Still, trap-neuter-release seems to be here to stay.

“Conservationists still protest the practice, but have gained little traction in their attempts to suppress the practice,” said Bryan Kortis, national programs director for Neighborhood Cats, a TNR group that is based in New York City with branches in New Jersey and Hawaii. “This is due to their failure to offer any practical alternative solutions to cat overpopulation, and the public’s general support of TNR as measured by random surveys.”

To Catch a Cat

Gillis attaches the string to the box trap, unwinds it from the spool and takes her place a few yards away near the van. As she sits in the van with the thread in her hand, it’s a waiting game. To her left is a pair of binoculars.The first two cats are caught within 10 minutes of setting up the trap. One black and one tan, both of them at the same time. Gillis pulls on the string, the trap comes down with a clang, and the cats go crazy. Gillis springs into action, running over with a blanket to cover the top of the trap and the cats immediately settle down.

The next cat takes a bit longer to catch. So she resorts to pulling out a can of Fancy Feast to get that scent on the road. Gillis says these cats deserve nothing but the best, so they don’t use generic wet cat food. She jokes that each can contains three tiny shrimp and that it would be fine for human consumption if the apocalypse descended.

Gillis explains to me that her work requires her to find out from the people feeding the cats what their routines are. Maybe there is a whistle, or a special call, when it is food time. If things are too different, the cats can sense it, and the trapping won’t be successful. Sometimes caretakers hover nearby and it makes her job more difficult. She understands that they have an attachment to the cats, so Gillis has to balance being respectful to the caretakers while effectively doing her job.

In total, four adult cats are captured. A fifth cat eluded capture two separate times, walking up close to the trap at one point before scurrying away.

Gillis drives her furry cargo to the Snip Clinic, where she fills out paperwork for each. Soon after, other Alley Cat Advocate volunteers and community members arrive with captured cats. Paperwork is filled out for all of them in preparation for exams and operations that will happen in the morning

“Alley Cat Advocates handles over 6,000 calls a year, rents out traps, provides training, and funds surgeries through private donations and grants,” said Lisa Starr, shelter outreach director at the ASPCA. “They’ve built strong relationships with municipal and private animal shelters, members of the public, and community cat caretakers.”

The first two cats Gillis caught were neutered and received the FVRCP and one-year rabies vaccinations. They received a 30-day dose of flea treatment that kills fleas, ear mites and roundworms. And finally, while they are sedated, a quarter inch of the tip of the left ear is removed ear tip to identify them as sterilized, feral cats.

The third cat captured, a black and gray domestic long hair, was a female. She was spayed and received the same services that the other two received. She was not pregnant, and was not lactating which meant she hadn’t had a recent litter.

The final cat trapped was a black male cat, domestic medium hair. He had a slight irritation in one eye. He was neutered and received the same services that the others did. The vet examined his eye and found nothing amiss.

All cats were returned home safely on June 14, two days after they were caught.

Gillis said that the day after these four cats were caught, an Alley Cat Advocates volunteer went back out to that community and caught five more.

Gillis was fine company and conversation came easy. Normally, she would be doing this work solo — something she said she enjoys. But today we talked. We talked about relationships, politics and our common appreciation for classic rock.

Once in a while, Gillis cares for a cat that needs medical attention — they go to ACA-trained rehab volunteers for recovery time. In those instances, she said, she can feel a bond with the cat, but realizes that the process is a revolving door and takes comfort in the notion that these cats will have good lives and end up being loved and appreciated.

“I value the life of all animals,” Gillis said. “So for me, getting this job was an opportunity to help those who can’t speak for themselves.”

She says this is her first job where she can’t find fault — it seems a perfect fit.

“I believe in everything we do,” she said. “To be able to say that, and mean that is a good feeling, a happy feeling. I get to educate people who want to learn but don’t have the resources. I get to help the people, and help the animals and help the people help the animals. It’s beautiful.”

An Organization Started on a Stroll

Alley Cat Advocates prides itself on running this trap-neuter-return program for unowned community cats.The organization’s executive director, Karen Little, started the organization in 1999. She moved to Louisville in the late 1980‘s. When she would walk back and forth to her job on faculty at the University of Louisville, from her home in Old Louisville, she would keep finding stray cats.

“We [she and her husband] needed to develop a plan to address that issue if only for the reason that I could walk back and forth not accumulating animals and/or not feeling horrible that I was leaving the issue unaddressed.”

Little traveled nationally to find possible solutions to the rising stray cat population. She wanted to know what progressive communities were doing. Trap-neuter-return started in the early 1990s in the U.S., and there was a lot of hope in the animal welfare world that this process of identifying unowned cats, trapping them, spay/neutering them and returning them to their environment was the best way to stabilize cat population growth.

“Alley Cat Advocates, in partnership with Metro Animal Services and Kentucky Humane Society, administers one of the most sophisticated and effective community TNR programs in the United States today,” said Neighborhood Cats director Kortis.

“An important thing to understand about TNR is that, like any other policy, its effectiveness depends on how it is executed,” said Kortis. “It can be done well with excellent results or poorly with no progress being made. For example, targeting resources like trappers, spay/neuter surgeries and funds, to high need areas in a community can be a key tactic. Achieving high sterilization rates within colonies of cats and neighborhoods — as close to 100 percent as possible — is also essential to achieve significant nuisance abatement as well as a stable and eventually declining population.”

It comes down to caring

Felty was happy to get the cats back. She puts food out for them every night and every morning and feels they are happy cats. She jokes that she would like to take them all fencing with her.“I have a soft heart,” says Felty. “I want to keep them healthy. If they are sickly, they will cause other animals to get sick.”

Felty feels Gillis did a great job and says she can tell she cares, which she believes is the most important thing.

Gillis says soon after she got this job, she realized that she often finds help for cat caregivers who provide for other living beings even when they have scarce resources for themselves.

“They take the time and with what little money they have, or extra food or whatever and they take care of these cats that keep coming around,” said Gillis. “So it kind of gives you some faith in humanity.” •