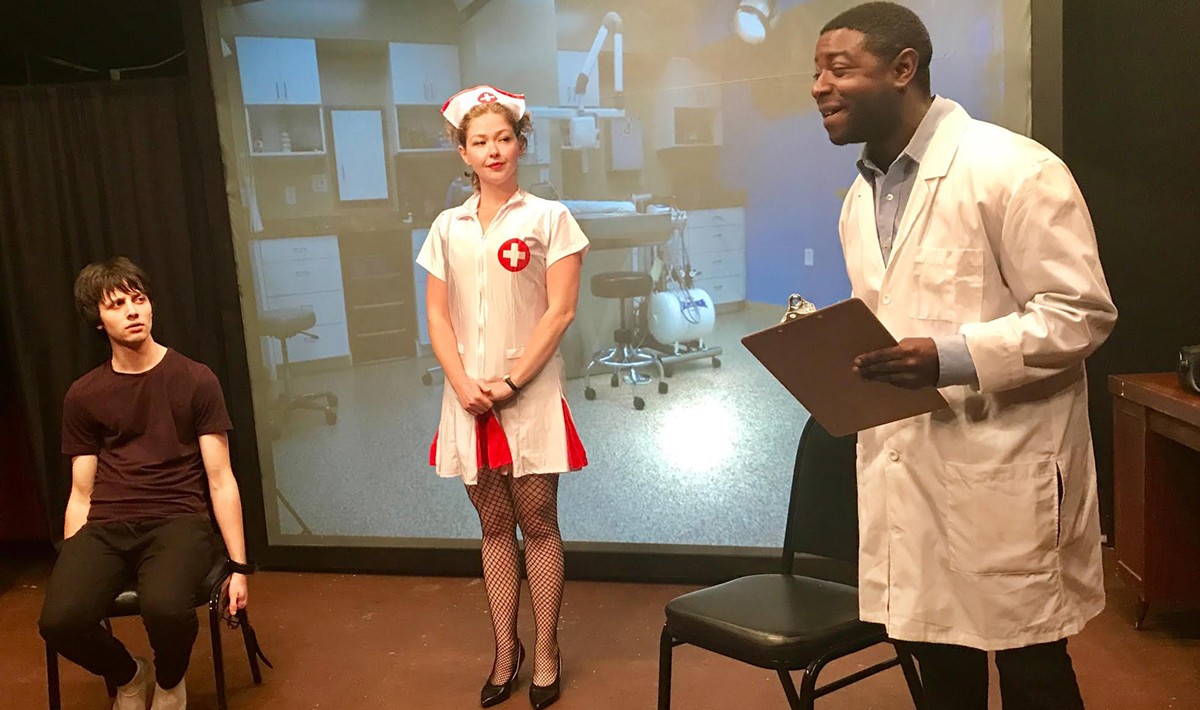

Onstage there is a man strapped to a chair. A sexy nurse is grinding in his face, while a doctor with a clipboard looks on and takes notes.

What began as a realistic, but tense, circumstance has devolved into a satirical take on the morals espoused by the anti-LGBTQ crowd.

We’re watching “An Invasive Procedure” a new 10-minute play, onstage through Sept. 17 at The Bard’s Town’s 7th annual Ten-Tucky Festival.

Now, when I say new, I mean this play is brand-spanking new. Not only has it never been performed before, but despite having been onstage as an actor for numerous plays, the playwright, Jacob Cooper, has never written a play before.

In a phone interview, Cooper talked about why he took the plunge into the world of writing.

“This idea was kind of just one of those conversations you have with a friend where one of you say like, ‘Oh, that would make a really funny one act,’ and I don’t know… just an idea that hung around in the back of my head,” he said.

Finally, Cooper decided to write it down and submitted it to Ten-Tucky, which became the platform for his first production.

All around the country, 10-minute play festivals give writers a chance to see their first work in front of an audience.

Offering that initial opportunity is one of the reasons that Doug Schutte, the owner and head of theater offerings of The Bard’s Town, started Ten-Tucky.

“I think, for me, the biggest thing was maybe the chance to get more Kentucky folks onstage,” he said.

The Bard’s Town often features Kentucky playwrights and their longer plays, but a ten-minute play festival allows Schutte to spread an opportunity around to eight playwrights.

The festival hasn’t launched any superstar careers, but many of the Ten-Tucky playwrights have also written full-length plays, some of which have even been produced around town.

While 10-minute play festivals are held nationwide, Louisville has a special connection to the art form.

It was born here, at Actors Theatre of Louisville, and it had thrived there since it was introduced in 1989, as part of the Humana Festival of New American Plays, and as a part of its robust acting apprentice program. Because of that rich history, it was something of a shock when earlier this year Actors dramatically cut back their commitment to 10-minute plays.

The annual Ten Minute Play Contest, and the slots at the Humana Festival for the winners of it, was suddenly eighty-sixed, and Actors told LEO in a statement there are no plans to bring it back:

“The National Ten-Minute Play Contest is associated with The Ten-Minute Plays, three ten-minute plays that run at the end of the Humana Festival of New American Plays each Spring. We are no longer producing that particular evening of short plays, and running the subsequent contest in conjunction with it. At this time there are no plans to reinstate it.”

Now, let’s step back and see what this means.

Suppose Cooper, or someone like him, has decided to get serious about writing plays, practicing the craft and maybe even someday going pro.

It’s a tough business to break into, and as the ever-shrinking pool of governmental funding continues to dry up, it’s getting even tougher.

And full disclosure, when I’m not at my day job, I’m writing plays, so I know of what I speak, but I can’t claim to not have some personal feelings here.

Let’s say Cooper would have submitted a ten-minute play to the Actors Ten Minute Play Competition when it was still running and he won.

Actors Theatre is a big deal. Getting a play onstage there is a chip in the big game, and a launching point for professional playwrights who’ve gone on to serious careers.

If Cooper’s play ended up in The Humana Festival, important people from all over the country would see it.

He doesn’t have that opportunity anymore. But festival’s like Ten-Tucky still offer him the opportunity to see his play up on its feet.

Steve Moulds is a playwright with national success and ties to Actors Theatre. He also happens to be a Louisvillian by marriage, and, at the moment, he’s a playwright-in-residence professor at Vanderbilt University. We talked to him about the importance — and the pitfalls — of 10-minutes plays.

“The name of the game for playwriting is getting your work in front of an audience,” he said.

But Moulds said 10-minute plays are a good introduction to the process of theater.

“The most valuable way that a 10-minute play helps a playwright is if you have the opportunity to be part of the production process, from beginning to end,” he said. “If you’re in rehearsals, if you are talking to the director, if you’re involved — that’s such a valuable experience.”

But he also pointed to drawbacks. Writers can pick up bad habits that don’t help them in writing full-length works. Maybe they focus on the quick joke —which is fine in and of itself, according to Moulds— but it can keep new writers from learning bigger lessons.

“That’s not really the same as dramatic story telling like, let’s follow this idea to it’s conclusion, let’s probe this question of human nature as far as we can take it, past what a normal person would think,” he said.

In this discussion of whether 10-minute plays are still important, we can talk about art, but it’s all too easy to get caught up in the math, and the idea of being a success, which of course in our society is defined as getting paid.

Nobody in Ten-Tucky gets paid, but there is an intrinsic value to creating something with people you care about.

“To me it’s really important because it’s what the festival is — it is this community festival celebrating community, and it gives people the responsibility and the opportunity to create it as they want to and bring it to life,” said Shutte.

The value of 10-minutes play, like the value of any art, is so deeply subjective that to find that value you have to weigh a pieces effect on an untold number of souls — hobbyists and professionals, friends and family, strangers who just happened to buy a ticket.

As for Cooper, on Friday night after the lights came up, he was elated and smiling, high on that crazy mix of endorphins you get when you open a play. He got his feet wet, and seemed to be thrilled.

Will he be back? Will he write more plays?

Forget about the future or function of the ten-minute play: What is Cooper’s future?

“I would really like to do it again, I don’t know that I would consider myself a writer yet,” he said. “I don’t have any delusions that anything I write is going to be worthy of being performed. So I guess I feel like I got lucky on this one.”