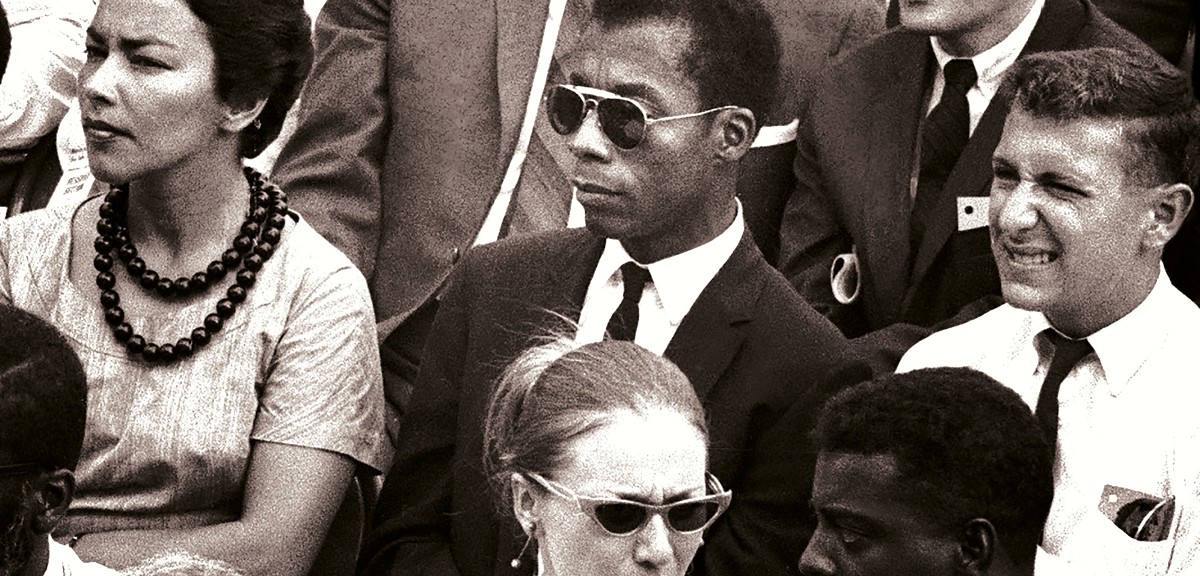

Sitting on the pew among the mourners at the funeral of Martin Luther King Jr., author James Baldwin admits that he held back his tears because he felt, echoing what he undoubtedly knew everyone in that room struggled with, that if he began crying he would never stop.

As a white man, and one born two years after King’s death and so almost entirely ignorant of this historical circumstance, I can lay no claim to such sorrow. I am left with nothing to be circumspect about. And yet the emotion of the moment, cast upon the movie screen, finds its way into the depth of a grief and a horror whose power I had never appreciated.

The day after having seen “I Am Not Your Negro,” it is this fact alone that disturbs me. I am unable to do anything but make an account of why, at the finish of the film, as the lights rose almost apologetically, I remained in my seat in Cincinnati’s Esquire Theater, unsure of what to do, in tears.

On that Sunday afternoon, I left the theater and stood at the curb. I had lost control of my emotions, and I wept on the street. The world stood transfigured, transformed, as if I had been torn from any comforting self-protections. This is the power of film, of course, and director Raoul Peck’s effort, surely one of the most important films of the century, as prescient as it is necessary, left me as rattled as if I’d seen a ghost.

It occurred to me the morning after that I had in fact seen a ghost. Peck told NPR’s Terry Gross that, in his early readings, Baldwin “was speaking directly to me,” and his genius is in allowing Baldwin to speak directly to me, and to everyone in the dark theater. The message I received, however, is qualitatively different from the other patrons.

The African-Americans in the room, from what I could hear of their affirmative responses to both the passionate words of Baldwin and the bloody scenes of the 1968 Oakland riots and the violent response to the Ferguson protests, heard their lives and their history validated and confirmed. I instead found myself jarred from a complacency I’d inherited and, to my detriment, both been taught by my culture and the existence of which I had remained entirely ignorant. Much of the deeper history was simply not present in my social studies classes or textbooks.

The power of film lies in a number of strategies, all of which are orchestrated by Peck to an unnerving and compelling degree. For one, we are made privy to images that many of us may never have seen, and which almost certainly have never been featured in a high school textbook. Martin Luther King Jr., for example, marching along a street lined with white people holding Nazi flags and signs inscribed with blatant swastikas and the chilling words, “White Power.” I have never seen these images before, and they are certainly not what I have been taught of, for lack of a better term, my heritage as a white person — or what I imagine it to be.

That we see this same image today is troubling enough; that it is history repeating itself — that such images found their way into America when there were undoubtedly veterans in those same streets who had actually fought the Nazis, the graves in Arlington fresh with its casualties — is doubly damning. The demons we harbor have never been healed, and Baldwin, who died in 1987, knew this deeply.

What Peck has done is remarkable. In much the same way as Ron Fricke’s “Baraka” and “Samsara” — two films that likewise deal with issues of inequality and its attendant violence — we as audience, as witness, are confronted with the humanity that lies beneath the concepts of black, of slavery and, as painful as it is to say, of nigger.

We are confronted, in the juxtaposition of an entirely white cast singing and dancing in the movie “Pajama Party” with images of lynched black men, with the disparity between what we view as our realities of prosperity and the suffering that the power structures and systemic racism have explicitly caused and continue to perpetuate and to allow. Even if it was not us, today, who hung those men in the trees, we are responsible for attending to the justice of an entire people, the descendants of slaves — the people, as Baldwin says, who built this country.

Yet, in the spirit of Baldwin himself, who claims himself to not be racist, who looked on white people with compassion, the movie does more than condemn, though it certainly achieves a sense of rage. Baldwin says in the course of the film that the black man feels rage because he is being held back, because he is not allowed to live out his destiny. The white man, he says, feels rage because he is afraid. In this sense, the film challenges the image the white man — and the white woman — holds of himself and herself. The image of prosperity and innocence, especially that following the Second World War, has repressed the horrors we have committed to not only achieve this prosperity but to limit it, refusing to share it with an entire population of people.

Baldwin himself asks the movie’s most definitive question, in order that the audience might gaze at themselves unflinchingly, as deeply as they are asked by the film’s images to gaze at the faces of black children grieving for their dead parents. Essentially, he asks whites to consider what it is we are most afraid of, and what it is we are projecting upon the African-Americans who are, above all else, Americans.

“The question,” he says, “the white population of this country’s got to ask itself, is why it was necessary to have a nigger in the first place… If you think I’m a nigger, then it means you need it, and you’ve got to find out why… and the future of the country depends on that.”

The film is clearly painful to watch, if one considers this question dearly. Baldwin’s challenge to us, that we might accomplish justice, is that we see ourselves as we are, no matter how monstrous.