Les Waters is having a busy summer. In addition to preparing for the upcoming season at Actors Theatre of Louisville (ATL), where he serves as artistic director, he directed the premiere of Anne Washburn’s “10 out of 12” for New York City’s Soho Rep. In Los Angeles, he directed a revival of the Matthew Sweet, Todd Almond musical “Girlfriend,” which ATL audiences saw in 2013. In a week or so, he’ll return to New York to direct an Off-Broadway production of Lucas Hnath’s “The Christians,” which premiered in 2014 at ATL’s Humana Festival of New American Plays. The revival, which finds four of the original five ATL cast members reprising their roles, moves on to Los Angeles after its New York run.

By every measure, ATL is flourishing under Waters and his team. The regular season lineups have featured fascinating repertory in splendid productions. The Humana Festival bills have been bold, energizing and diverse. And the company just landed a $1.2 million grant from the Roy Cockrum Foundation to support its outstanding Apprentice/Intern Company — a program that yields its own special legacy.

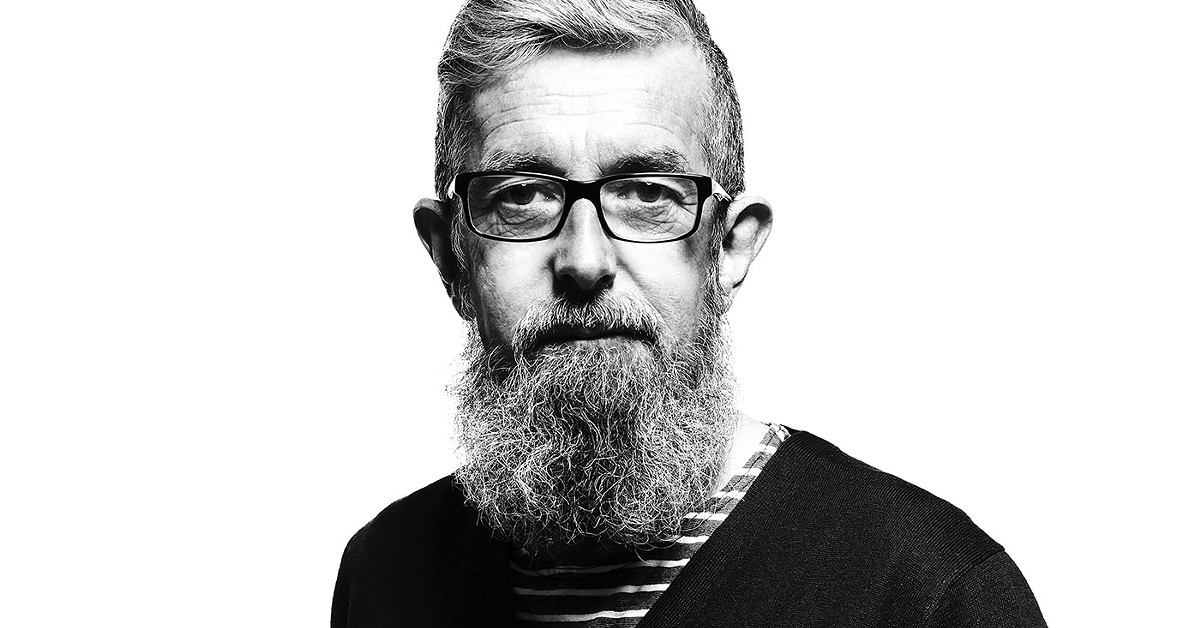

Last week, I sat down with Waters, not to talk about the upcoming season, but to ask him about other things — including his passion for plays that express a strong sense of place.

“My mother’s family are all from a part of Lincolnshire on the east coast of England, and my mum was a first-generation town dweller,” Waters told me. “Most of her family came from very small villages and worked either as agricultural laborers or servants in the big house. My dad worked in a steel mill. I got interested in the theater because of a history teacher who did the school play, and I would read [theater critic] Ken Tynan’s pieces about theater in The Observer. In the years before I went to college, I would go down to London to see plays, and I saw a Royal Shakespeare Company production of “The Relapse” (John Vanbrugh). There were country people in it who came on stage with absolutely bizarre accents and were sort of idiots, and I remember thinking, ‘This is hysterically funny because these actors are fantastically skilled, but this bears no relationship to my life whatsoever, none whatsoever.’”

So Waters began searching for plays about agricultural laborers — like the people he knew — and what he found was a disappointing mix of romantic myth and negative stereotypes. “The romance is that they’re in tune with nature, but there’s this terrible negative side that you’re a country idiot — a bumpkin. It made me furious, and I think I’m part of a generation of working class English kids who ended up in the theater who wanted to see their real experience on the stage.”

That chance to contribute to that cause came when Waters worked with the influential playwright Caryl Church on a Joint Stock Theatre Company production called “Fen” (1983). The play is set in the region where Waters’ family has its roots, and the Joint Stock process involved immersive research and interviews in the locale. “There were bits of dialogue based on things my mum said,” said Waters. “And she was a bit furious.” (The Joint Stock research process has some elements in common with the research Naomi Iizuka used in crafting ATL’s production “At the Vanishing Point,” the Butchertown-based play that Waters directed for the 2004 Humana Festival and revived in a stunning production last season.)

“The interesting thing is that Caryl Churchill’s ‘Fen’ is my mother’s life on stage,” said Waters. “The central character isn’t based on my mother, and very little of the narrative of the play has anything to do with my mother’s life, but the texture and the feel of the play is my mum and it’s very precise about where it’s geographically located. It doesn’t say so in the script, but anybody from these three counties in Lincolnshire would be able identify the location. It’s a play that had enormous resonance in London and was a huge hit in New York.

“I remember at the first preview thinking, ‘People are going to look at us as if we have two heads, speaking this strange accent — but the more geographically precise and local it was, the more the bigger resonance it had. So my passion for this kind of playwriting stems from the fact that I didn’t think my cultural tradition was being shown on the stage.”

Louisville, said Waters, is well-suited for this sort of approach (which also played a role in last season’s Humana productions “That High Lonesome Sound,” which used bluegrass music as a prism for looking at Kentucky, and “The Glory of the World,” the innovative (and controversial) celebration of Thomas Merton.

“If you live in some cities, like London or New York, those cities have a kind of imperial swagger that makes them indifferent to how you feel about them. But other cities do care. And I think it’s a very interesting thing to do, to say, ‘Look at this about your town,’ and to find new ways to show it to people.”

It’s also, according to Waters, an approach that encourages a philosophy of inclusion. Because he felt that his own culture had been excluded from the stage, he seems to feel a strong empathy for others in the same situation. “I think it’s important as a director to champion writers, actors and directors who bring distinctive voices to the stage. It’s a duty.”

And we’ll see evidence of that starting September 1, when August Wilson’s “Seven Guitars” opens in a production directed by Colman Domingo, whose play “Dot” (about an African-American family rooted in a Philadelphia neighborhood) was one of the highlights of last season’s Humana Festival.

For information about the ATL season, connect to actorstheatre.org or call 502-584-1205.