The Kentucky Derby isn’t one of those things that started small and grew bigger over time. Oh, it certainly has gotten bigger – bursting at the seams today at Churchill Downs, and telecast to millions around the world. But in no way did it start out small. The very first Kentucky Derby, in 1875, was planned to be the greatest horse race ever held – and pretty much was. What follows is an excerpt from my book “The Kentucky Derby — Derby Fever, Derby Day and The Run for the Roses” (due out in October, from Shircliff Publishing and Carpe Diem Books). In the excerpts below we travel along crowded Louisville streets to attend the first Kentucky Derby, in 1875, then step into the stirrups with exercise rider Charlie Davis as he works Secretariat at Churchill Downs in preparation for the 99th Run for the Roses.

A cloud of dust hung over the city for days leading up to the first Kentucky Derby. Excitement built, and by Monday, May 17 — yes, the first Derby was held on a Monday — the scene was set in Louisville for the first Kentucky Derby. All day long people traveled to the track. Many traveled by mule-drawn trolley cars which ran along recently laid tracks to the southern side of the city. Some rode horses. Many walked. And wending their way along the crowded streets came private carriages hauling the well-heeled, dressed up in their Derby finery. Not that anyone yet knew what the de rigeur Derby outfit should be. But these were the original style-setting Derbygoers, and by every report, the first Kentucky Derby was a huge style show. Of course, ordinary people arrived in more ordinary clothes. The business class dressed neatly in tailored outfits, ladies in proper dresses. But surely all — from every walk of life — crowned themselves with a best hat from the top shelf.

Who were they? Many were leading citizens. Many were regular working people. African-Americans came to the track. They didn’t sit in grandstand seats — but took up good vantage points along the rail and in the infield, as ready as everyone to enjoy the day and root for their favorites. And from all accounts, a tremendous number of women claimed attendance. Interesting, that, since few women in 1875 attended baseball games or prize fights. But horse racing was considered, well, more gente. Plus, American women were increasingly stepping out of the kitchen to enjoy the same experiences as men. Pretty soon they’d be voting!

What did the first Derby-goers find at the new track on the south edge of the city? No doubt many wondered exactly what they would find. Horse races were widely attended at whatever venue they might spring up. But this was different. This was a Kentucky Derby, at a new, permanently located racetrack.

And just to show how new an idea that was, we don’t think racetrack was even a word yet. But it would be …

Colonel Meriwether Clark

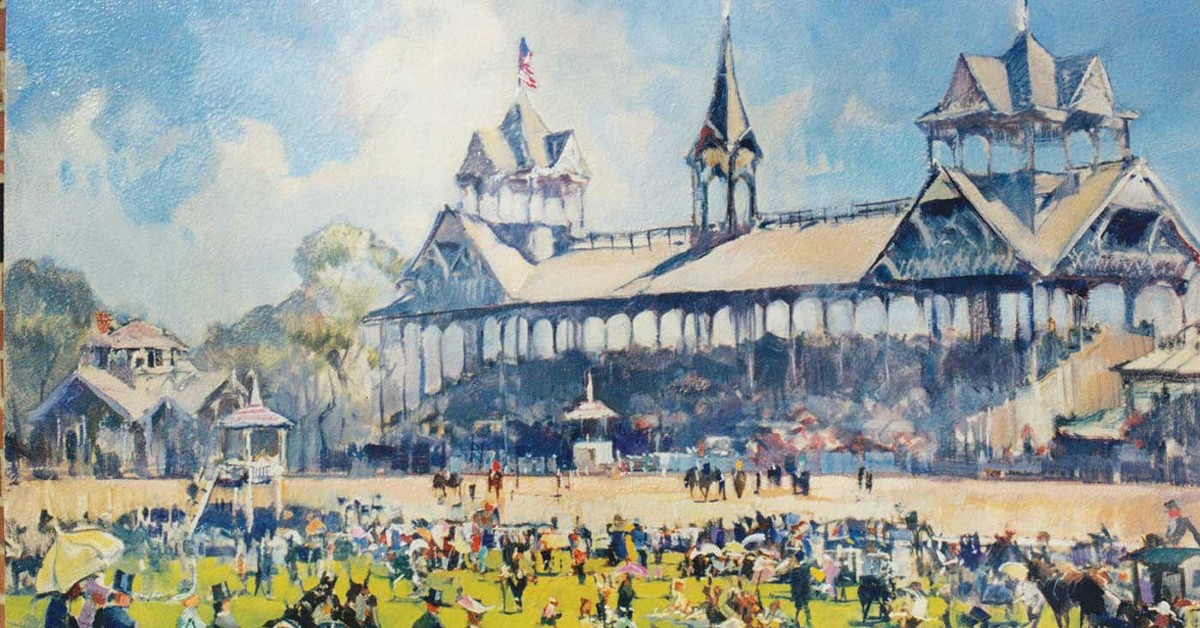

For a permanent location for his Louisville Jockey Club course, Colonel Meriwether Lewis Clark leased a section of his uncle Henry and John Churchill’s broad farmland at the edge of the city, about three miles south of downtown. This is the eventual origin of the name of the Kentucky Derby track. At first the racing grounds was simply referred to as the Louisville course. Sometime in the 1880s a reporter dubbed the track “Churchill Downs” — with a nod to the Churchill family’s farmlands, and drawing on the Derby’s Epsom Downs origins in England. (Referencing British origins is always a natural in horse racing. It’s why we have furlongs.)The broad, loamy, farmland soil of the tract proved ideal for a racing surface, though in modern times, track superintendents have learned to change the dirt regularly and mix sand in with it to promote drainage. Clark also set to work on a grandstand, horse barns and maintenance facilities. Plus a small, well-appointed Clubhouse. A share of stock in the Louisville Jockey Club and Driving Park Association wasn’t without its benefits. A stockholder was entitled to admission to an adjacent Clubhouse — still a sought-after perk today.

There’s a note somewhere that the paint was just drying on the grandstand by Derby Day. So it was a close call in timing and funding. Coming to the big day, horsemen arrived with their horses, setting up shop in the new barns. Officials were hired to fill racing posts, and everything was ready.

The track was laid out southwest to northeast — a one-mile oval track, with each straightaway one-quarter mile in length, and each of its two turns a quarter mile. The soil was perfect for stability. It was graded (horses pulling grading blades of course) and then harrowed to a smooth and springy surface.

Over time, nothing about the course’s dimensions or layout has changed. In 1893, the original grandstand on the east side of the track was torn down and replaced with a modern new structure on the west side that opened in time for the 1894 Kentucky Derby. That grandstand still stands, of course, topped by the beautiful Twin Spires. But the track – the dirt racing strip, over which the first Kentucky Derby horses ran — has not moved one inch since 1875 …

The enduring first-person account of the first Kentucky Derby is provided by the man who eventually made the Derby into the world-renowned sporting event is it today. But on this day, he was a just a Louisville boy, drawn by natural curiosity to the excitement swirling around the thing. Years later, Colonel Matt J. Winn penned his autobiography “Down the Stretch,” with sportswriter Frank Menke, taking us back …

“The first Derby Day, I remember as if it were yesterday,” recalled Winn. “It was May 17, 1875. I was 13 — nearing 14 — when Col. M. Lewis Clark, the Louisville sportsman, and his associates of the racetrack which is now Churchill Downs, were making ready for the opening. My father decided to be there. He wasn’t a horseplayer. But this was more than a race day. It was a festival, and my father felt he ought to be at the track to see if the ‘goings on’ would be worth all the fuss the people had been making. He promised to take me along to see the opening of the new track, and the running of the Derby, provided I performed a few extra chores, which were completed in world’s record time.

“I was up at dawn. It was clear, sunshiny and warm. Father hitched the horse to the wagon, which he generally used in hauling groceries from the wholesale houses, and we were off through the greatest traffic jam Louisville had known up to that time.

“The mule-drawn street cars were loaded to the limit (with race goers.) Those who had horses, hitched them to carts, or buggies, and were on their way. Others horsebacked to the track, while thousands walked ...

“Many guesses have been made as to the exact spot I occupied when I saw the inaugural running in 1875,” Winn continues. “I saw it from a standing-up position on the seat of my father’s wagon, anchored in the infield, which was known as the “free gate area,” meaning that if you didn’t wish to pay a fee to get into the grandstand section, you could walk, or drive, through a special gate to the infield – without charge.

“It was a thrill for me, this first Derby, with crowds swirling around the infield, the grandstand a riot of color, tenseness in some places, unrestrained enthusiasm elsewhere, as the time neared for the horses to parade to the starting line in readiness for the race that all Louisville, and most of Kentucky, had discussed for months. I don’t suppose I was the only 13-year-old boy in the infield, but I guess by sitting on the seat of my father’s wagon, and standing on it during the running of the Derby, I had the best view of any 13-year-old boy.”

Winn goes on to set the racing scene, describing the back-and-forth discussions of the relative merits of the Derby horses — most of which centered around Chesapeake, owned by Hal Price McGrath, whose colors were green, with an orange band. “Before the race started,” Winn says, “I had come to believe that Chesapeake was the greatest race horse in all the world; that nothing could run as fast.”

Alas, it wasn’t Chesapeake’s day that day in May. The race went to another horse, whose 19-year-old rider Oliver Lewis, was also clad in green and gold — Chesapeake’s overlooked stablemate Aristides. It was the first Derby upset — in the very first Kentucky Derby.

Secretariat

Secretariat came to the 99th Run for the Roses as the most celebrated horse in decades, with a huge chestnut colt’s every move. To make matters more tense, Secretariat had run third in his final Kentucky Derby prep in New York, and many wondered if Secretariat was really all he was hyped to be. In particular, they wondered whether the son of Bold Ruler could handle the 1 1/4-mile Derby distance.At Churchill Downs, exercise rider Charlie Davis and groom Eddie Sweat kept a round-the-clock watch on Secretariat in the days leading up to the Derby. As the media and public pressed closer, Davis and Sweat kept the curious at bay — never leaving their horse’s side. A painful abscess had been discovered in Secretariat’s mouth. That’s a common ailment, and reliably treated with familiar remedies, but with every antenna tuned to the Big Red horse, members of trainer Lucien Laurin’s stable kept the news to themselves. Luckily, the abscess healed and Secretariat began training like his old self again.

“I am going to say this,” says Davis, taking a deep great as he talked recently with this reporter, thinking back over the decades to the days leading up to the Kentucky Derby. “Secretariat give me a better vibe than even Riva Ridge did. He showed me how much hold to take of him. Do this … (Davis demonstrates, holding his hands and imaginary reins at just the right place) … and he just glide, like you was in a ski boat. So I just give him his head and he just galloped on out. Like I tell everybody, I wasn’t the pilot, I was the co-pilot.”

Eight days before the Derby, Secretariat worked six furlongs in 1:12 3/5, with Davis aboard. Then on Wednesday of Derby Week he sizzled five furlongs in 58 3/5 seconds.

“He gave me a vibe,” Davis adds. “Like your kid is talking to you — but it was a strong vibe, like, ‘Hey, man, I’m the man, you’re just along for the ride.’”•