The story of what Jackie Robinson endured to integrate major-league baseball in 1947 doesn’t need any embellishment from Hollywood. The facts are more than enough. Unfortunately, the movie industry just can’t help itself. As usually is the case with movies based on real events, the people who produced “42” played just fast and loose enough with the truth to annoy those who have researched the story and interviewed some of the key participants.

Take the portrayal of Pee Wee Reese, for example. As a friend of the late Louisvillian who was captain and shortstop of the Brooklyn Dodgers when Robinson joined the team, I’m disappointed by the way Hollywood changed him. The movie would have us believe he was a callow and confused yokel from the sticks. Not so. He was a mature, sophisticated leader who was respected by everyone in the Dodgers’ clubhouse.

Even at that, however, it could have been worse for Louisville. The movie producers blessedly ignored what happened when Robinson came to Louisville at the end of the 1946 season to play for the Montreal Royals against the Louisville Colonels in the “Junior World Series.” The Royals, champions of the International League, were one of the Dodgers’ Class AAA farm teams; the Colonels, winners of the American Association, occupied a similar role with the Boston Red Sox.

The games in Louisville were played in Parkway Field, which was located off Third Street and separated from the University of Louisville campus by a viaduct that’s still there. Here’s what historian William Marshall had to say in his book, “Baseball’s Pivotal Era,” a well-researched account of the years from 1945-1951:

“Robinson came to Louisville in a hitting slump, and the apprehension he felt about playing there further affected his play. Although he played well in the field, Robinson had only one hit in 11 at-bats, as the Royals lost two of three to the Colonels. Each time he came to bat he was met with a chorus of boos, off-color remarks, and foul language. ‘The tension was terrible,’ he remembered. ‘I was greeted with some of the worst vituperation I had yet experienced.’”

It’s quite possible Robinson, a graduate of UCLA, actually used the word “vituperation.” And there’s no doubt it was a good way to describe his treatment at Parkway Field. Apologists may argue that the ugliness was at least partly because Robinson, then playing shortstop, figured to challenge hometown hero Reese for his job in the spring of 1947. But the main reason was the color of his skin. Like most of America, and all of the South, Louisville was a segregated city.

The movie also was unkind to A.B. “Happy” Chandler, another Kentuckian who played an important role in Robinson’s story. In 1945, Chandler, a former governor of the commonwealth, gave up his seat in the U.S. Senate to succeed Judge Kennesaw “Mountain” Landis as commissioner of baseball. His first controversial decision came just before the 1947 season, when he banned Leo Durocher, the Dodgers’ flamboyant manager, from organized baseball for a year because of his association with actor George Raft and “known gamblers.”

In the movie, Chandler’s only appearance is in a scene that depicts him calling Dodgers’ executive Branch Rickey to tell him about the Durocher decision while getting a manicure. I don’t know if Chandler ever got a manicure in his life, but I do know that he abhorred people who “put on airs.” That was one of the reasons he despised Durocher. Just as he courted the support of the working class as a politician, so did he stand up for the players as baseball commissioner, supporting the establishment of a players’ union and a pension plan in defiance of the owners who employed him.

He also defied the owners in the Robinson case. On Aug. 27, 1946, the 16 owners met privately and, by all accounts, were overwhelmingly against allowing Robinson to play for the Dodgers in 1947. However, after allegedly meeting with Rickey in the cabin behind his Versailles, Ky., home the following winter, Chandler decided to ignore the owners and give Rickey the green light to let Robinson play for the Dodgers in 1947.

From then until his dying day, when asked why he had defied the owners and his own Southern heritage, Chandler always gave the same answer: “I’m going to have to meet my maker someday … If He asks me why I didn’t let this boy play and I say it’s because he is black, that might not be a sufficient answer.”

Outrageously, the movie takes that line away from Chandler and gives it to Rickey, who is played superbly by Harrison Ford. His face glowing in triumph, the “movie Rickey” attributes the quote to the owner of the Philadelphia Phillies, who finally caved in to media pressure after threatening to boycott Robinson’s first appearance in the, ahem, City of Brotherly Love.

Earlier, I used the word “allegedly” to modify the historic meeting between Chandler and Rickey. I got the story directly from Chandler several times during the course of our friendship. However, my friend Dave Kindred points out there is no mention of it in any of the Rickey biographies. But wherever it took place, there had to be a meeting between Chandler and Rickey, because integration in 1947 was impossible without the commissioner’s support.

At least the movie only gives Chandler a cameo appearance. Red Barber, the Dodgers’ radio play-by-play announcer, gets a much larger role, which is unfortunate because John C. McGinley’s rendition of him is a disaster. A native of Georgia, Barber had a Southern accent full of molasses and honeysuckle. He also liked to use quaint down-home phrases. (When the Dodgers were in a good position, for example, Barber said they were “in the catbird seat.”)

When Barber moved from the Cincinnati Reds to the Dodgers, some skeptics figured his style would never be accepted in the ethnic melting pot that was Brooklyn. But just as the borough welcomed immigrants of all races and nationalities — even black ones from the Deep South — so did Brooklyn embrace Barber. On steamy summer nights, when everyone in the borough’s neighborhoods and tenements and bars had the windows open, his mellifluous voice was impossible to escape.

In the movie, unfortunately, McGinley uses an accent that is difficult to define. It sometimes sounds more British than Southern. Whatever, it sounds nothing like Red Barber.

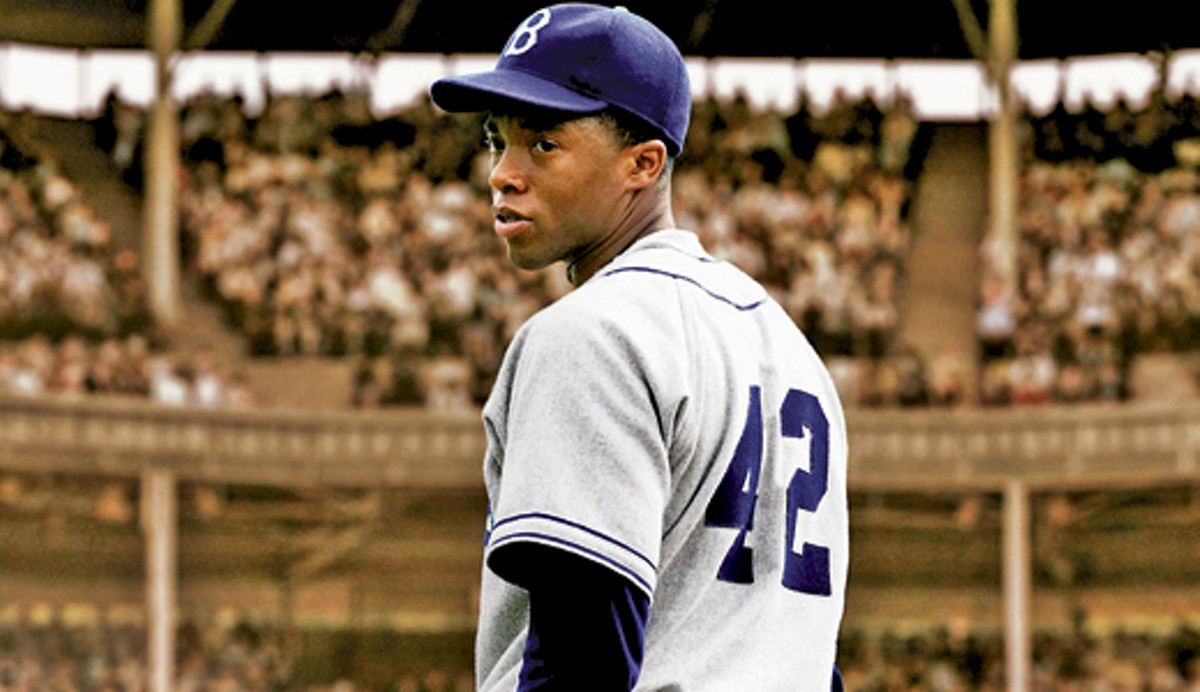

In fairness, I should say the movie is not without merit. Besides Ford’s portrayal of Rickey, which I think is Oscar-worthy, Chadwick Boseman and Nicole Behare are superb as Jackie and Rachel Robinson. Although Boseman doesn’t attempt to emulate Robinson’s famed pigeon-toed gait or his high-pitched voice, he gets right his batting stance and, mainly, his fiery spirit. And the real Rachel, now 90, has whole-heartedly endorsed how perfectly Behare gets her combination of beauty, courage and grace.

I also liked Christopher Meloni’s portrayal of Durocher, who was known as “Leo The Lip” because of his brashness and candor. When Reese joined the Dodgers as a rookie in 1940, Durocher was the team’s playing manager and his position was shortstop. But instead of turning his back on Reese, he showed him how to be a big-leaguer, both on the field and off it. Reese once told me that if he admired one of Durocher’s expensive alpaca sweaters, Durocher would literally take it off his back and give it to him.

Like many big-league players, Reese interrupted his career to serve in World War II. He was on a troop ship coming home when he got the news that Rickey had signed Robinson to a Montreal contract. Asked if he was worried that Robinson would take his position, Reese said, “If he’s good enough to do it, he’s entitled to it.” During spring training of 1947, when a few Dodgers tried to start a petition to protest Robinson joining the team, Reese refused to sign it. That, along with a team tongue-lashing by Durocher, quelled the movement.

The movie’s most compelling scene depicts the historic gesture that happened the first time Robinson accompanied the Dodgers to Cincinnati. Accounts differ about whether it happened in pre-game batting practice or early in a game. Regardless, as the crowd in Crosley Field was pelting Robinson with racial slurs, just as the crowd at Louisville’s Parkway Field had done less than a year earlier, Reese casually walked over to Robinson and slung an arm around his shoulders.

As Reese told me years later, he wanted to send a message not only to the jeering fans but to some of the Dodgers who still were refusing to accept Robinson. The message was simple: “This is my teammate.” The moment was brief, but Hollywood turns it into a soliloquy where Reese mentions the Civil War and his roots and says he wants his Louisville family and friends in the crowd to “know who I am.”

I promise Reese would have been upset and embarrassed by that. If anything, he always thought he got far too much credit for befriending Robinson. “Jackie’s the one who deserves all the credit,” Reese would say. “He was the one getting threatened, not me.” More than anything, Pee Wee was a pragmatist. He knew Robinson could help the Dodgers win. He also knew he could not tolerate one teammate being treated differently on the field and in the clubhouse. So, as the captain, he did what captains are supposed to do: He led by example.

“Please don’t make me out to be some kind of civil-rights leader,” he would say. “It wasn’t like that. I just treated Jackie like I would want to be treated if I were in his shoes.”

Robinson’s shoes were not a comfortable place to be. The movie does a decent job of showing the racism that existed in baseball at that time. When he was moved to the new position of first base for his rookie season, he had to beware of base-runners who tried to slash his Achilles tendon with their metal spikes. As the movie shows, Phillies’ manager Ben Chapman was one of many rivals who spewed venom at Robinson from the dugout. And so many pitchers threw at Robinson’s head that, eventually, he became the first big-leaguer to wear a protective batting helmet.

But the movie’s saving grace is that its basic premise is right. Because of Jackie Robinson, America changed profoundly in the summer of 1947. In Cincinnati, for example, the racists were counteracted by excursion trains of blacks who came from as far away as Atlanta, Birmingham and Chattanooga to witness the miracle of a black man playing in the major leagues. They got the worst seats in the house, in the far corners and the outfield bleachers, but they did not care. It was enough to see No. 42 in person.