DEAR LIFE

By Alice Munro

Knopf, 319 pgs., $26.95

In the ring for world’s greatest living short-story writer is England’s William Trevor, age 84; in the far corner is Canada’s Alice Munro, age 81. And it’s a fact: The two writers are not only close enough in age to be longstanding contenders, but you rarely read of one these days without mention of the other in the championship bout for the title of short-story master or mistress.

Except the word “mistress” in this context is not OK. Just as “poetess,” in another context, isn’t either. But “poetess” is how some people described Greta back in the early 1960s in Vancouver, where “housewife” and “mother,” in that order, were the order of the day.

What was clearly out of order, then or now: Greta having sex with Greg, an actor traveling on the same train as Greta and her daughter Katy. But as Greta is having her rendezvous, Katy goes wandering from the berth where Greta has put her to sleep. When Greta finds Katy missing, she panics, but this scenario isn’t the whole story in “To Reach Japan,” the opening story in the latest collection, “Dear Life,” from Alice Munro. It’s one component of the story, and who’s to say life isn’t built on moments of melodrama? Not Munro, who here demonstrates, in 14 stories, her greater skill: registering life as it is lived — simpler moments, perhaps, which doesn’t make them, in Munro’s hands, any less decisive for her women and men, regardless of time or place.

The time frame covered in “Dear Life” goes from World War II to more recent decades. The place can be Vancouver or Toronto, but mostly it’s out of the way — not the center of towns and not quite the full countryside of Munro’s native Ontario. And while she certainly doesn’t shortchange the male characters, the women are this observant writer’s main concern (particularly the female character in the collection’s four closing, autobiographically based stories, which, according to the author, are not stories at all, “only life”). That woman is the writer’s mother. —Leonard Gill

SWEET TOOTH

By Ian McEwan?

Nan A Talese/Doubleday,?320 pgs., $26.95

“I wanted characters I could believe in, and I wanted to be made curious about what was to happen to them,” explains the narrator of Ian McEwan’s new novel, “Sweet Tooth.”

That is true of any novel, but such a statement reveals just how much is at stake in a novel about an obsessive reader. The book must be obsessively readable itself, if only to demonstrate that character’s defining trait.

Part Jane Austen romance and part John le Carré spy novel, “Sweet Tooth” lives up to such heavy expectations, thanks mainly to its narrator, a young woman named Serena Frome. The daughter of an emotionally reserved bishop in rural England, she cultivates a bookish air in her teenage years, in parallel with her rather conservative politics — both of which serve her well when she takes a job at MI5, the British equivalent of the CIA.

Set in the tumultuous early 1970s, this book vividly evokes England’s political and economic unrest, the violence in Ireland, and the last thrums of Cold War paranoia. Serena’s devotion to contemporary fiction and her knowledge of the latest novels by Anita Brookner, A.S. Byatt, and others lands her an undercover assignment. Posing as a representative for a literary foundation, she is tasked with encouraging a young writer named T.H. Haley to produce a politicized novel. It’s no spoiler to say they become lovers.

Highly intelligent yet deeply naive, Serena proves a fascinatingly unreliable narrator — excellent company for these 300 pages. Ultimately, her bookishness may be her most endearing trait, as well as her most empowering. Describing her favorite novels, she sets high standards: “I wanted to feel the ground beneath my feet,” Serena explains. “The invented had to be as solid and as self-consistent as the actual.”

Writing with a sharp eye for detail and character, for period detail and literary whimsy, McEwan follows her demands to the letter. —Stephen Deusner

THE UNTOLD HISTORY OF THE UNITED STATES

By Oliver Stone and Peter Kuznick?

Gallery Books, 750 pgs., $30

For all of the gridlock and polarities in the land, there are still a few subjects on which people of all political persuasions — left, right, or whatever — are likely to agree. And one of them is that Oliver Stone, the filmmaker and professional controversialist, cannot be entirely trusted as a source of real-world history.

To take a couple of instances, ranging from the monumental to the ridiculous, Lyndon Johnson did not conspire with the likes of New Orleans businessman Clay Shaw to murder John F. Kennedy, nor did Richard Nixon call his wife Pat “Buddy.”

These examples — from Stone’s movies “JFK” and “Nixon” — are but two of the many errors, ranging from the clearly fabricated to the merely mistaken, to be found in the work of Stone, who has now taken his method of free-handed invention-cum-analysis to the subject of “The Untold History of the United States,” which is both a 10-part pseudo-documentary now airing on Showtime and a book co-authored with American University historian Peter Kuznick.

Yet, like another noted fabulist, one Will Shakespeare some 400 years ago, Stone is a dramatist of imagination and power whose renderings of real events (as well as of avowedly fictitious ones) manage to illuminate and reveal even as they avail themselves of copious amounts of poetic license. So it was with the Bard’s “Richard III”; so it is with Stone’s “Untold History.”

While it is certainly true, for example, that Henry Wallace, FDR’s vice president for his third term, had a following, it is laughable to present this literal-minded idealist of the left, whom the Democratic Party bosses did in fact shove aside to make room for Harry Truman, as a virtual messiah, complete with a crucifixion motif. And it is surely one-sided to characterize Truman only by his connections to the Kansas City Pendergrast political machine and by his somewhat effete childhood while making short work of his sterling military record in World War I and omitting altogether the career-boosting ad hoc work his Truman Committee did in investigating and exposing corrupt war profiteers.

But yes, as Stone and Kuznick suggest, for better and for worse, Truman abandoned the policy of friendly collaboration with the Soviet Union that Roosevelt had followed and Wallace would have continued and took a harder line consistent with a developing Cold War rivalry. Yes, too, dropping the bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki may have been aimed at Russia as much as Japan, which the authors posit.

And the authors are surely on solid ground in their efforts to de-emphasize the Anglo-American role in defeating Hitler compared to that of the Soviets, who for most of World War II engaged the bulk of the German army and suffered casualties in the tens of millions. In inveighing against the biases of the Cold War and of “greatest generation” historiography, however, “Untold History” overdoes it in the other direction. Virtually every crisis and malaise and threat to mankind of postwar history, right up to the present, is attributed to the predations of the American empire and its incorrigible military-industrial complex. Wars in Korea and Vietnam. Coups in Guatemala, Chile and Iran. Turmoil in the Middle East. All were either caused or exacerbated by this country’s “global imperialism.” Few of the conclusions of Stone and Kuznick are utterly without merit, but they are enhanced and magnified beyond measure by a relentless cherry-picking and conflating of actual sources and by the inclusion of some clearly dubious and uncorroborated ones. Still, Oliver Stone has narrative gifts, and they are in full display in “The Untold History of the United States,” a work that is more propaganda than history but a compelling and often enlightening read all the same. —Jackson Baker

THIS LIVING HAND

By Edmund Morris

Random House, 475 pgs., $32

Edmund Morris is best known for “Dutch,” his controversial official biography of Ronald Reagan. “Dutch” employed narrative techniques to describe episodes of Reagan’s life. Those techniques got more attention (mainly negative) than the book itself. That’s unfortunate, because Morris is among our best historical biographers. Morris has chronicled Theodore Roosevelt and Beethoven. His wonderfully digressive approach to huge lives places him on the shelf with William Manchester, Robert Caro and David McCullough.

Morris is a different sort of writer, something brought into clearer focus with the release of “This Living Hand,” a collection of essays published as he was compiling his larger works. The collection goes behind the scenes of Morris’ great biographies and finds him in a more loquacious mood than is generally allowed in the Halls of History.

The title essay, published in The New Yorker nine months after Reagan’s handwritten farewell letter to the American people in 1995, finds Morris at his best. Already aware of digital encroachments upon the sources of history, Morris pauses on the script itself. He reads the document as a capstone to years spent with Reagan’s vast epistolary output. But he breaks the proscenium, barely containing his emotional reaction, while writing this essay in the Gipper’s post-presidential office in Century City, Calif. He is describing his last goodbye with a great man who gave him great privilege. Regardless of your politics, it is informed and moving first-person history.

Morris also offers a bit of his own story, which is a fascinating, sprawling life that stretches from far-flung British colonial Kenya to Century City and includes a perhaps too personal but funny account of buying a suit on Savile Row.

This is a charming collection of historical insights from someone who has done the heavy lifting. Morris’ “Beethoven: The Universal Composer” has just jumped to the top of my must-read list. —Joe Boone

ESSAYS IN BIOGRAPHY

By Joseph Epstein

Axios Press, 603 pgs., $24

Let’s be honest. The trouble with a lot of biographies is that they are too long. Recent tomes on Winston Churchill, Lyndon Johnson and General Ulysses Grant come to mind. Sure, you and I might check them out of the library or give them to someone at Christmas, but will they actually be read? To ask the question is to answer it.

So call me a slacker. There is much to be said for HarperCollins’ “Eminent Lives” series of short biographies by excellent writers and even more to be said for Joseph Epstein’s “Essays in Biography,” 40 essays on knowns and lesser-knowns, none of the essays more than 30 pages.

Epstein is no slacker. He has 22 other books on his personal shelf. I approached this one warily, having read only a little of his previous work. His roster of subjects is heavy on intellectuals such as Susan Sontag and Irving Kristol. So I skipped to names I knew, including Adlai Stevenson, Joe DiMaggio, W.C. Fields, Michael Jordan, A.J. Liebling and Malcolm Gladwell. And in every one of those essays I learned something I did not know or smiled at some well-turned phrase or fresh observation. Epstein at his best rivals H.L. Mencken or Christopher Hitchens.

He can play rough, as he does with Gladwell (author of “The Tipping Point” and “Outliers”), and he can be gentle to the point of adulation, as he is with Jordan and DiMaggio. Epstein is an intellectual who also likes sports. But the most touching essay is the last one in the book. Its subject is an old man named Matthew Shanahan, whom Epstein met on what he expected to be a brief and uneventful visit with his granddaughter at the Jewish Home for the Blind in Chicago. Shanahan, who was 88 at the time, proved to be a self-taught intellectual, widely read, liberal in thinking, and wise in many ways. They became fast friends. Epstein’s book is dedicated to him. —John Branston

HONKY TONK: PORTRAITS OF COUNTRY MUSIC

By Henry Horenstein

W.W. Norton, 144 pgs., $50

In the song “Blue Side of Lonesome,” Gentleman Jim Reeves gets to the existential heart of the honky tonk when he describes a tavern known as Three Teardrops. It’s a place, he says, where “the hands on the clock never alter” and “things never change.”

“There’s no present, no past, no future,” Reeves sings. “We’re the ones who have lost in love’s race.” This “Twilight Zone” sense of timelessness is the best thing about the black-and-white photographs collected in Henry Horenstein’s book “Honky Tonk: Portraits of Country Music.”

The stars in Horenstein’s book are only occasionally the stars. He’s captured a clean-cut Hank Jr. and a disheveled Waylon Jennings looking every bit the part of a young outlaw. But few of the portraits, which place golden-age icons like Porter Wagoner and Hank Snow alongside hippie outsiders like the Holy Modal Rounders, bluegrass legends like Jimmy Martin and Bill Monroe, and contemporary barroom warriors like Dale Watson, are as interesting as the images of the bars themselves and the country fans who gather to drown their sorrows or dance all night.

Horenstein’s photos of swinging doors, juke boxes, and barstools were taken across five decades, but, hairstyles excepted, very little changes: Bands pass around the tip jar, PBRs are raised in celebration, tour buses roll on to the next town and the next gig. Did I mention Dolly Parton? Or hairstyles?

There’s nothing wrong with Horenstein’s celebrity portraits. But everything’s right about his 1978 shot of the wall behind the bar at Tootsie’s Orchid Lounge, the essential Music City dive where bags of Lay’s potato chips, show posters, and a grimy American flag hang alongside Polaroids, newspaper clippings, and promotional photographs that tell the story of the bar, its patrons, and the Nashville Sound. Like a good old song, it’s a photo you can easily lose yourself in. —Chris Davis

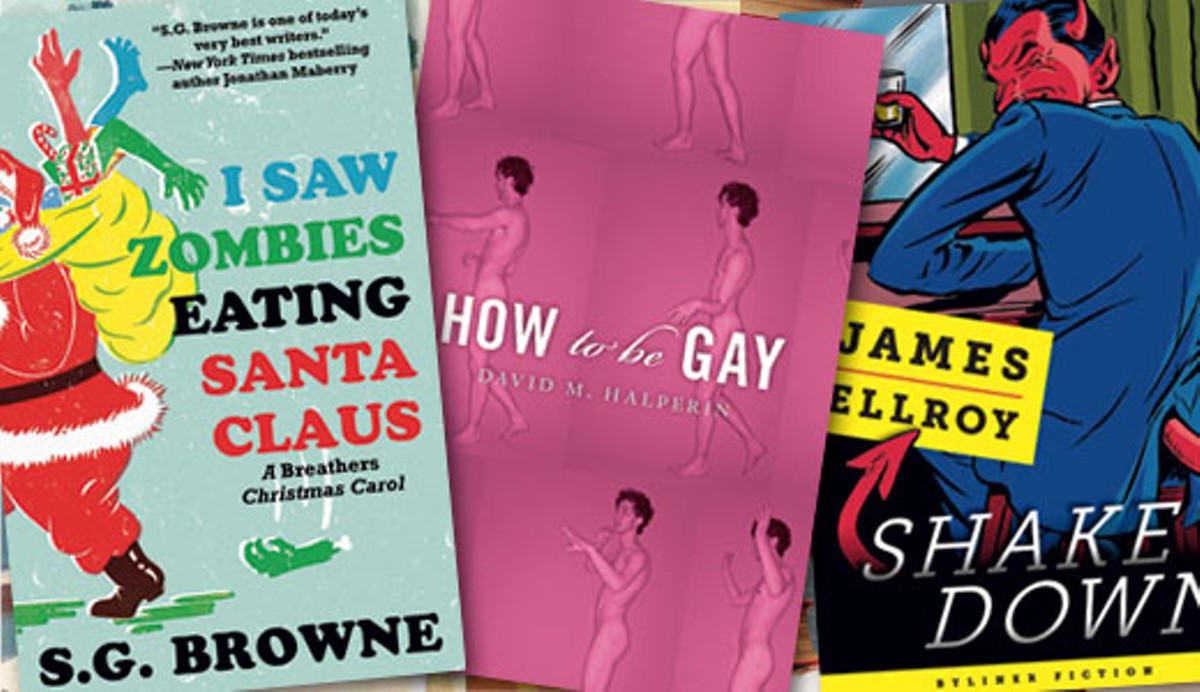

SHAKEDOWN

By James Ellroy

Byliner, 66 pgs., $1.99 (digital)

James Ellroy’s “Shakedown” is a classic little be-bop that fits in nicely with the great American crime writer’s canon. It is also published by Byliner, a company that produces digital books called “eSingles.” The publisher commissions original fiction and nonfiction that can be read in a single sitting, and other authors who have gotten the Byliner treatment include Jon Krakauer, Nick Hornby, Margaret Atwood, Amy Tan, Taylor Branch and Ann Patchett.

The complete title of Ellroy’s latest is “Shakedown: Freddy Otash Confesses.” Otash was a real-life ex-cop and private detective in the 1950s and ’60s. He was infamous in Hollywood for being the guy who could get the dirt on any celebrity, who would commit most any illegal, morally suspect deed to provide smut, gossip and innuendo for the pages of Confidential magazine. Photos and surveillance transcripts of favorite starlets shacked up scandalously? The public ate it up. But some of it Otash kept quiet and used to extort his victims. When Confidential died, however, Otash got mobbed up.

Ellroy knew Otash. In Ellroy’s magnum opus, “American Tabloid,” he has Otash wiretapping JFK’s liaisons with Marilyn Monroe, an event that did allegedly happen. Ellroy wades in historical truthiness.

“Shakedown” has Ellroy going back to this outlandish character, this time putting him in purgatory. It’s June 16, 2012, and Otash writes that he has spent the decades since his demise in a “penance penitentiary” but that he might go to a better place if he confesses his sins: “There’s heaven for the good folks, hell for the beastfully baaaaaad. There’s purgatory for guys like me — caustic cads that capitalized on a sick system and caused catastrophe.”

In “Shakedown,” Ellroy gives Otash a ghost writer who will plead his case before God: James Ellroy. It may sound a little mad, but he pulls it off with fearless, audacious writing — what he calls “scandal language,” the tabloid patois that spritzes the page (or e-reader) with energy. What results is an anamnesis of Otash’s foulest hits. “Shakedown” names names. —Greg Akers

HOW TO BE GAY

By David M. Halperin

Harvard University Press, 560 pgs., $35

In his provocative new book “How To Be Gay,” University of Michigan professor David M. Halperin makes a shocking claim that is sure to rile both gay activists and Christian conservatives alike: Being gay is not about sex, identity, or even love. Instead, being gay is about possessing certain sensibilities, specifically ones that embrace irony, Madonna videos, and a taste for interior decorating and Broadway musicals.

Halperin makes it clear early on that he is not interested in the politics of gay identity, the we’re-just-like-everyone-else mentality used by many gay activists in the fight for equality and one that made “Will & Grace” a huge hit among straight people. Instead, Halperin, whose college course of the same title as his book sparked conservative outrage when it was introduced in 2000, seeks to turn gayness away from politics and back into a form of expression. According to Halperin, gay men are unique in their ability to laugh in the face of tragedy and adversity, in their tinge of feminine melodrama, and in their deep appreciation for the movies of Joan Crawford. In fact, whole chapters of the book are devoted to analyzing one scene from Crawford’s classic “Mildred Pierce” and its effect on generations of gay men.

Sometimes these ideas feel slightly regressive, almost as if Halperin longs for the days of life in the closet; it is hard to imagine today’s gay youth being inspired by a black-and-white movie from the 1940s. But if Halperin is more “Glee” than Gaga, his arguments never feel dated. Gay culture is culture, he says, and everyone, even heterosexuals, can learn from it.

“How To Be Gay” is not the sex manual its title suggests, nor is it a straight-to-gay conversion blueprint the religious right may fear it to be. It is a careful dissection of the taste and style that define so many gay men. Joan Crawford would be pleased. —Sean Kelly Robinson

LOVE GOES TO BUILDINGS ON FIRE: FIVE YEARS IN NEW YORK THAT CHANGED MUSIC FOREVER

By Will Hermes

Faber & Faber, 384 pgs., $16 (paperback)

By referencing the title of a popular Talking Heads song, “Love Goes to Buildings on Fire” seems to be, at first glance, the latest in a long list of literature paying homage to the Big Apple’s pioneering punk and new wave scene. But after reading the first few pages, it becomes clear that author Will Hermes has not only created a partner to the Victor Bockris book “Beat Punks” but gone much deeper, examining everything from the jazz scene to the blood-and-booze-soaked glory days of CBGBs.

Hermes has certainly done his research. While books like “Please Kill Me,” the oral history by Legs McNeil and Gillian McCain that focused on the tumultuous, often violent interactions between the scenesters of the New York underground, Hermes instead talks about the intimate relationships that transcended music genres and helped mold modern music into what it is today. That doesn’t mean things were always pretty in this musical melting pot. Hermes points out verbal spats between Suicide’s Alan Vega and the Talking Heads’ David Byrne as well as the physical altercation between Handsome Dick Manitoba and Wayne County that could have ended in death.

In a little over 300 pages, Hermes manages to capture the sights and sounds of a city ready to explode with talent from 1972 to 1977. He also finds a way to effortlessly intertwine what New York’s citizens were going through during this time. The city’s financial crisis and rampant crime supplied plenty of song-writing fodder to musicians, regardless of genre.

And while it’s easy to point out that New York shouldn’t be considered the mecca of everything cool in the mid-’70s, Hermes’ extensive coverage — from Hector Lavoe to Joey Ramone — makes it hard to dispute that the city really was the place to be if you were a musician looking to make it. —Chris Shaw

I SAW ZOMBIES EATING SANTA CLAUS

By S.G. Browne

Gallery Books, 208 pgs., $14.99

Though Christmas is behind us, zombie lovers should not overlook this gory gem, in which it took author S.G. Browne only 15 lines in the opening chapter before mentioning a decomposing corpse.

Turn the page, if you dare, and more details emerge: “When the human body dies, the bacteria that live in the stomach continue to feed. Though instead of eating the food we’ve consumed, they start eating away at us and excrete gas, which builds up in our abdominal cavity until usually something gives way. Usually the intestines but sometimes the torso. Either way, it’s not something you want to occur on a first date.”

It’s right about here when most readers understand they are not reading “Twas the Night Before Christmas.”

Welcome to the world of romantic zombie comedy — rom-zom-com for those in the know — and the decidedly twisted holiday story, “I Saw Zombies Eating Santa Claus.”

When I was a child, a visit to a department store Santa was a terrifying experience. People today are clearly made of hardier stuff, and Browne introduces us to the adventures of Andy Warner, who tells us when we first encounter him, “I am a zombie.” But none of that “Hollywood crap,” he assures us. No, “We are normal, sentient, reanimated corpses who are gradually decomposing and could use some serious therapy.”

And so could I, after learning this: Zombies “hate getting shot in the head,” “you’re not going to win any spelling bees when the gray matter explodes out the back of your skull,” and — this is important — “you tend to speak in vowels while getting eaten alive.”

Like this: “Ooooo.” And “Eee aaa ooooooo.”

Browne — or Andy Warner — has this to say about being a zombie: “If you’ve never woken up in a body farm wearing a Santa suit with your brains blown out the back of your head, you wouldn’t understand.”

Rudolph had that pesky shiny nose; Warner has his blown-out brains. He has just escaped from a zombie research facility and decided to elude his captors by wearing a Santa Claus suit. I guess that’s the comedy element of rom-zom-com. And the rom? Well, he encounters a girl who … oh, forget it.

If you’re not a real zombie, you wouldn’t understand. —Michael Finger