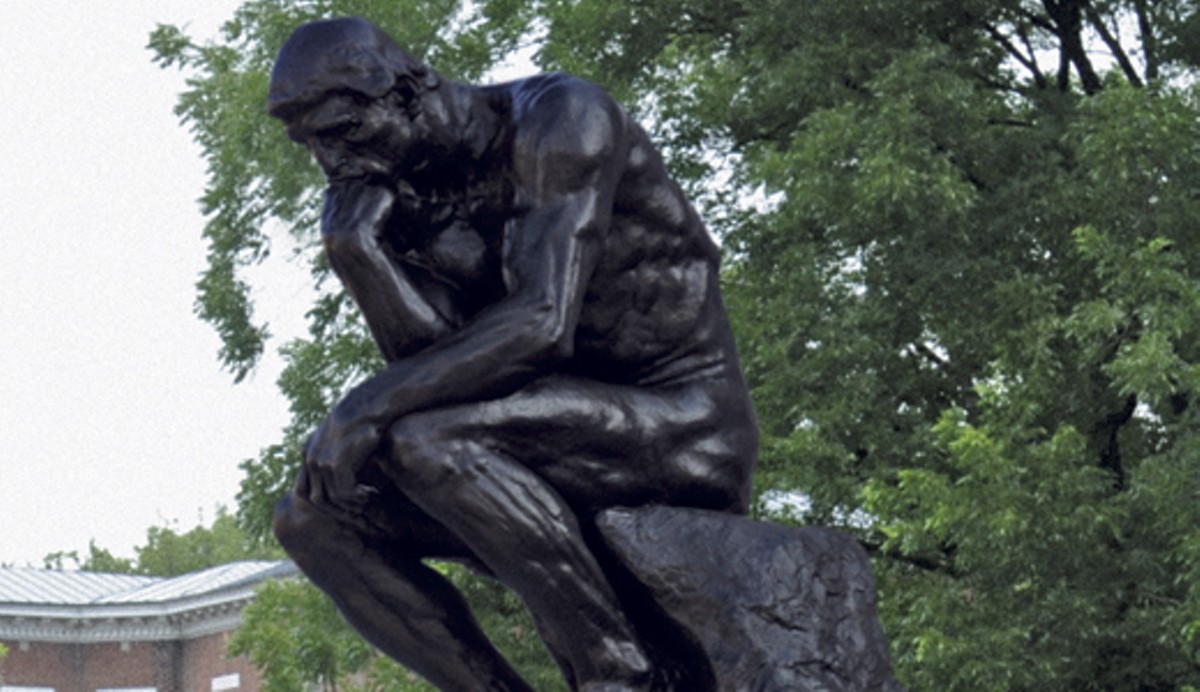

"Look at this very handsome man,” says Nick Peak, a Cardinal Ambassador trainee, as he points to Auguste Rodin’s “The Thinker.” On a perfect spring day, complete with chirping birds and a blowing breeze, the political science and economics major is practicing what to say about the famous sculpture, part of the speech he gives on University of Louisville tours.

“This is The Oval,” the junior continues, “and we consider it the official entrance to the campus. It houses some of our oldest and most prestigious buildings. ‘The Thinker’ represents the knowledge of higher education, and it’s very fitting it’s on our front steps.”

The road back to handsome has been rocky for “The Thinker” due to a decades-long battle to conserve the iconic statue. Because of chemical changes and corrosion, it spent many years covered in a Kermit the Frog hue. The conservation finally happened in 2012 because of the efforts of three U of L colleagues: associate professor of art history Christopher Fulton, fine arts professor emeritus Dario Covi, and Hite Art Institute galleries director John Begley.

The University of Louisville is home to the first full-size bronze cast of Rodin’s masterpiece. The French sculptor supervised its casting with more than 20 authorized copies to follow. The others are currently scattered around the globe, in such places as the National Museum of Western Art in Tokyo, the Sydney Opera House, and Stanford University in California.

The sculpture started out surprisingly small. Rodin’s 1888 work “The Gates of Hell” was based on Dante’s “Inferno”; centered atop the doors was a small, 27-inch “Thinker” looking down at hell. Rodin became so enamored with the figure (said to be his interpretation of Dante) that on Dec. 25, 1903, it was cast in bronze, enlarging it to about 6 feet tall.

Rodin described it as “a naked man seated upon a rock, his feet drawn under him, his fist against his teeth, he dreams … What makes my ‘Thinker’ think is that he thinks not only with his brain, with his knitted brow, his distended nostrils and compressed lips, but with every muscle of his arms, back and legs, with his clenched fist and gripping toes.”

It was shown at the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition, also known as the St. Louis World’s Fair. Henry Walters bought the work for his Baltimore home; it was later moved to his self-titled art gallery (now the Walters Art Museum). When the statue was put up for sale in 1948, the estate of Louisvillian Arthur Hopkins bought it for $22,500.

When Hopkins, a former alderman, died in 1944, his will stipulated that funds had been set aside for the purchase of “The Thinker” to “be given to the City of Louisville to be placed in either Central Park or Cherokee Park …” In 1947, the Committee on Monuments was formed, eventually seeking permission from the court to place “The Thinker” at U of L, stating they felt it “would be much more effective if placed against a formal background, such as a library, a museum, or an institution of learning, rather than in a public park.”

It was positioned in front of the Administration Building (now Grawemeyer Hall) on March 25, 1949.

Though a fitting backdrop for “The Thinker” aesthetically, the university setting was not without problems. Over the years, the iconic statue became a popular target for toilet paper and even graffiti. “When I first came to Louisville in 1956, markings were already on it,” recalls fine arts professor Dario Covi. “It was a playful thing to the students. I stopped it.”

As the elder statesman of the group, Covi has been battling apathy toward the sculpture for years. When he first saw “The Thinker,” it “at once … appealed to me both for its large scale and for the pose of a person in deep thought. It never failed to move me as a most expressive monument.” Unfortunately, the graffiti reoccurred in the 1960s.

Bur rather than hire an expert in art restoration, the university opted to have maintenance crews try to clean off the paint instead. The repeated cleanings resulted in the removal of the sculpture’s original patina, the oxidation process that occurs on the surface of bronze.

There were minor restorations over the years at the urging of art professors, especially Covi. “The neglect (was) not from lack of enthusiasm from the art department,” says art history professor Christopher Fulton. “There is a heightened awareness of the sculpture.”

Fulton researched “The Thinker” in 2005 and discovered Louisville’s statue is the first sculpture. While all casts are considered equal, he found records showing that this piece was the original of the series.

Soon, Fulton, Covi and Hite Art Institute director Begley joined forces to get “The Thinker” fully restored.

In 2006, the trio, along with Jim Grubola, then chair of fine arts, met with experts and art conservators from the Philadelphia Museum of Art, home to the largest Rodin collection in America. They came up with a diagnosis for the ailing work, but unfortunately, the money for conservation wasn’t available.

“Before we did anything, U of L wanted to know the risks,” Begley says. “(The university’s) counsel had to sign off. It was never a top priority of the university. I just don’t believe they understood how it had changed over time and how much from its original state.”

Fulton agrees. “Well, the sculpture was definitely taken for granted,” he says. “The very fact it was allowed to fall into ruin and turn sickly fluorescent blue-green visibly showed how little respect it was given.”

Finally, after years of pleading to the administration, U of L gave the conservation group the go-ahead in 2011.

“We have to take care of it,” Begley says. “I mean, it’s not just ours — it’s the world’s — and it’s our responsibility to treat it right.”

On Dec. 3, 2011, “The Thinker” was removed from its stained pedestal. Upon its return on Feb. 18, 2012, it was placed atop a new limestone pedestal by Muldoon Memorial Co. of Louisville, who also did the original.

During the two months it was away, the conservators removed the green corrosion and restored the statue to a dark brown patina with a hint of green, a color to which sculptor Rodin was partial. A protective wax coating went over that.

The $74,000 restoration cost came from federal and private sources. Kentucky received federal funds earmarked for The Oval renovation project. Since “The Thinker” conservation was not originally included, U of L President James Ramsey had to ask Gov. Steve Beshear for permission before proceeding.

And as it turns out, “The Thinker” is technically owned by the state, not the city. “When U of L moved from being a municipal university to part of the state system in the early 1970s, all assets of the university became part of the state,” explains Mary Lou Northern of the Mayor’s Office.

Since 1949, the location of “The Thinker” has been on the fifth step of Grawemeyer Hall. Just to be sure they had it right, Fulton contacted scholars, conservators and museum officials to find out if they believe the statue should be indoors or out. Most of the copies are outdoors, so it was no surprise many of the experts agreed to keep it there.

“The more I consider the sculpture, the more I like it where it is,” Fulton says. “It stands like a beacon for anyone entering The Oval from Third Street and guides visitors to the heart of campus. Now that the sculpture is fully conserved and repatinated, it will endure environmental threats much better than before. We have installed a regimen of cleaning the statue every couple years and of inspecting it at regular intervals for any signs of degradation.”

Louisville is known for its horses, bats and Muhammad Ali, but very few realize we are home to one of the original “Thinker” casts.

“We need to educate our students and the public about the sculpture,” Fulton says. “Not just about the fact that it’s the first cast, but about the work’s importance to world culture and the history of ideas. And ‘The Thinker’ is the quintessential example of (Rodin’s) unique artistic vision. The fact that the Louisville (statue) is the first one made gives us some bragging rights and is good fodder for cocktail parties, but it’s much less important, truly, than the meaning of the work for those who see it and allow it to work upon their consciousness.”

Fulton plans to continue his research and begin a study titled the “Rodin Research Project.” He hopes a definitive book about the sculpture will result, as well as an online exhibition.