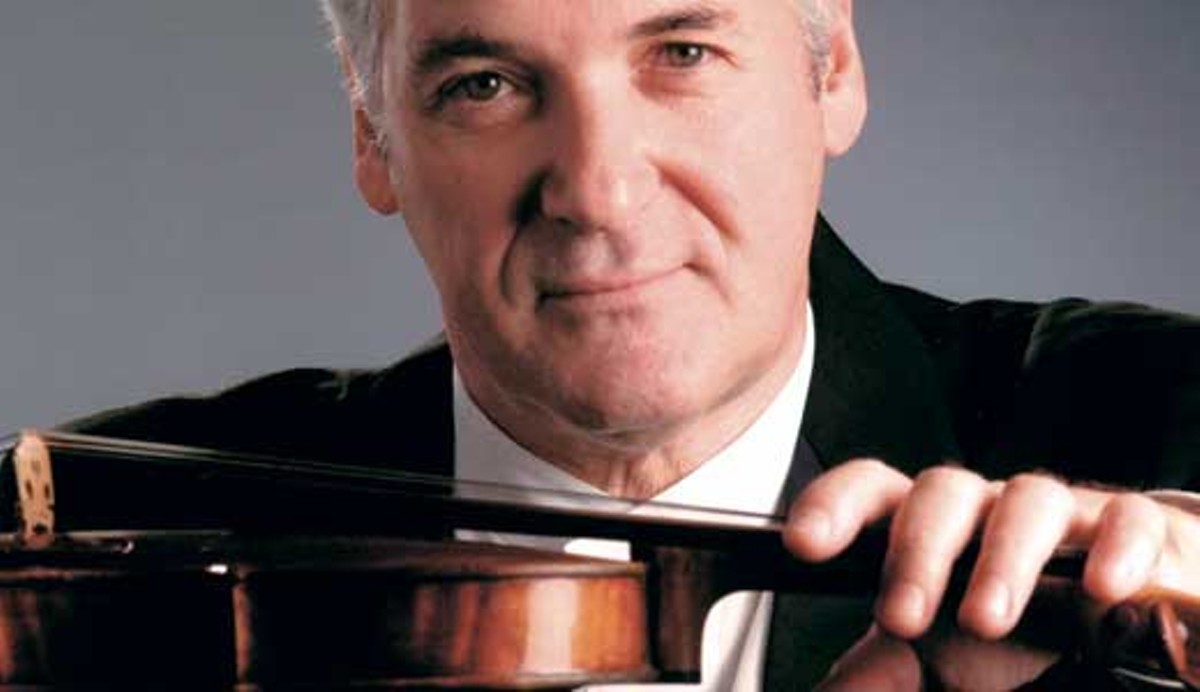

Growing up in Tel Aviv, violinist Pinchas Zukerman caught the eye of Isaac Stern and fiddled around with cellists Gregor Piatigorsky and Pablo Casals. Zukerman maintained a lifetime friendship with Casals, who played in the White House for President Kennedy. It was that kind of circle for Zukerman, and as his own fame grew, the soloist virtuoso branched out into a wider musical world, becoming a conductor and teacher (he was a pioneer of videoconferencing lessons with students around the globe) and a kind of eloquent advocate of the art of music. For a time he was married to actress Tuesday Weld. And he got expert advice from Jascha Heifetz, who told him, “Always play in tune.”

“I’m kind of a bridge between the old and new,” says Zukerman, 63, who appears in Louisville Thursday night in Whitney Hall as guest conductor and soloist with the touring Royal Philharmonic Orchestra of London.

“All the people that I knew,” he says with a satisfied sigh, thinking back to the 20th century with PBS interviewer Charlie Rose. “Now that I’m teaching, I tell about the people I knew — and pass on the feeling and the value system of those printed notes. That’s really what it’s all about. For actors, it is Shakespeare. For us, it is Bach and Beethoven.”

Or, for this night in Louisville, it is conducting Brahms (“Symphony No. 4”) and Mozart (“Overture to The Magic Flute”), then stepping off the podium to perform the Bruch “Violin Concerto No. 1.” Playing and conducting. Kind of like Artie Shaw, with his clarinet and band, barnstorming over the dusty highways of the 1930s. Only today, Zukerman and the Royal Philharmonic began a two-month tour of North America in Florida, coming north through Louisville to Ottawa, then on to Chicago and finally California. By jet, of course.

But always with the music.

“What is amazing is we can repeat all these things through a lifetime,” Zukerman says. “The Beethoven concerto. The Mendelssohn concerto. All these masterpieces.”

And the stories that go with them.

The Brahms “Symphony No. 4,” on the bill here, for example, is the composer’s last, written in 1885. And Johannes Brahms’ last public appearance, in Vienna, in 1897, was for a performance of the work. Brahms biographer Florence May describes the emotional scene as Brahms was spotted in the artists’ box in the balcony, and the orchestra and audience rose together in a thunderous salute for their hometown hero.

“The applauding, shouting house, its gaze riveted on the figure standing in the balcony, so familiar, and yet in its present aspect so strange, seemed unable to let him go,” writes May. “Tears ran down his cheeks as he stood there, shrunken in form, with lined countenance, strained expression, white hair hanging lank; and throughout the audience there was a feeling of stifled sob, for each knew they were saying farewell. Another outburst of applause, and yet another. One more acknowledgement from the master. Then Brahms and his Vienna were parted forever.”

Is the symphony, itself, so climactically emotional? Brahms summing up his life in music? More about anticipation, Zukerman believes. All stemming from the symphony’s first two notes. “It starts on an upbeat — da-dum — 4-1, clearly anticipation,” Zukerman explains in a series about Brahms done for Canadian Broadcasting. “That right there gives you a chance: What do I do with those two notes? We, as conductors, always want to hear that beginning as coming from some deep abyss, or dark area, into the light. Anticipation. Tension.

“Not to get too analytical,” he continues, “but a lot of times the orchestra starting this piece will be at a slight storm. A storm meaning they are not together. But that’s exactly what it should be. Obviously they are two quarter-notes written together, and you have to play them together. But at the start, sometimes they are not. That’s the magic of music, how we as musicians, practitioners, can actually put it together where it sounds right, according to The Bible — the score.”

Royal Philharmonic Orchestra of London

featuring Pinchas Zukerman, guest conductor and soloist

Thursday, Jan. 12

Whitney Hall, Kentucky Center

584-7777 • kentuckycenter.org

$30-$85; 7:30 p.m.