A motivated batch of 75 local artists and gallery owners gathered on Jan. 17 at the Garner Furnish Studio on East Market to baggie up slices of bologna, which they then affixed to 5-by-7-inch pieces of cardboard. The slices of lunchmeat were then driven to the Speed Art Museum and submitted as official donations to the “Louisville 27: Community” installation to be unveiled at a “Brown-Forman Art After Dark” event, which took place this past Friday.

Surprisingly, Speed Museum officials did not toss the bags of bologna into the trash, instead storing them in the Café’s walk-in refrigerator until they were to be put on display with the other 200 or so, non-emulsified submissions. Due to space constraints, only a fraction of the 75 pieces of lunchmeat were displayed — but the point still came across quite clearly.

All of the art submitted was on sale for $27 a pop, with profits from the event benefiting Speed’s childhood education programs.

So what was it about Speed’s “Louisville 27: Community” installation that riled 75 art lovers enough to lampoon a charity for children’s education with baggies of lunchmeat? The typical complaint lies primarily with how the museum went about soliciting donations for the event.

Late in 2009, Speed posted an “open call” for submissions to “Louisville 27: Community.” The open call stipulated that each donated 5-by-7-inch piece of art would be anonymous until it was sold at the set price of $27 (in honor of Speed’s opening in 1927). Some local artists — none of whom were solicited directly — rallied in opposition to the open call, which they considered a slap in the face to the local art community, and the latest in a string of requests from various auctions and charities to donate their work.

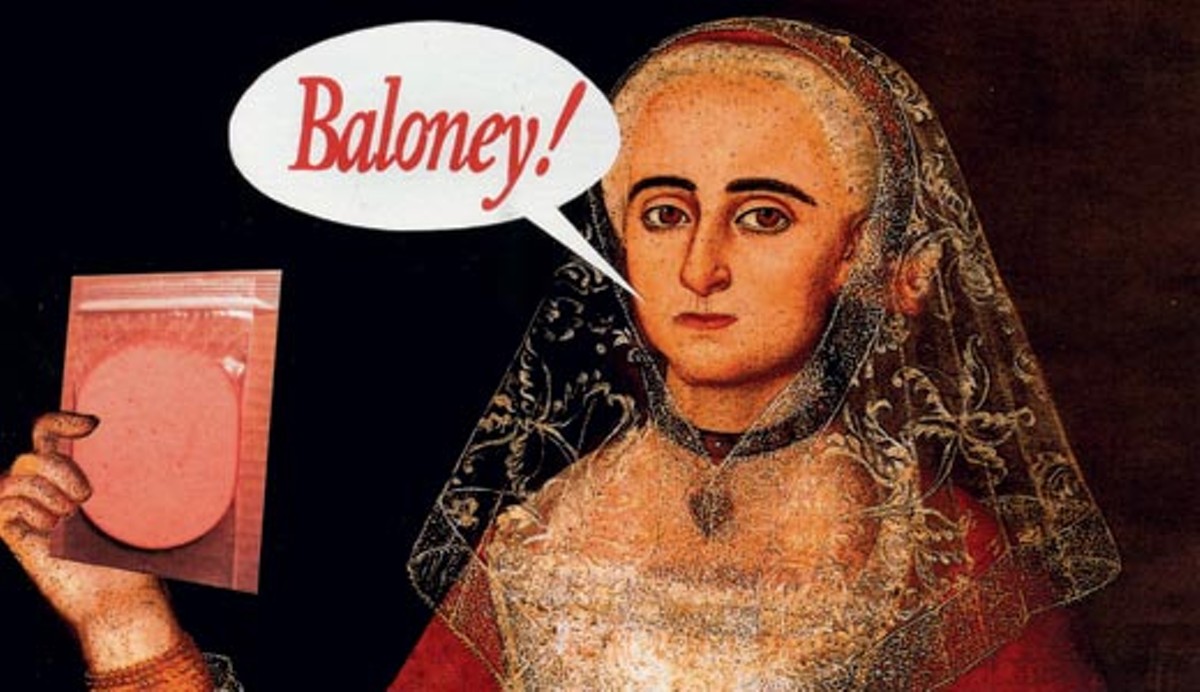

In further protest, outraged artists launched the “Speed? Baloney!” campaign which included a Facebook page that served as a forum for folks to state their complaints about the Speed and the Louisville art scene in general. Some artists on the online forum said they received only a few donation requests each year, while others claimed to have been solicited much more frequently. Lisa Austin posted that, since becoming an artist in 1982, she’s been “asked almost every week to donate a piece of art.”

Although most commenters on the “Speed? Baloney!” Facebook page were Speed detractors, there were a handful of people who came to the museum’s defense. “This isn’t a fundraiser for the Humane Society or the Fraternal Order of Police,” wrote Daniel Pfalzgraf. “It is for the Speed Art Museum and the children’s educational programming. There is a direct link between the cause and the artists, unlike so many of the auctions you feel you are getting bombarded with asking for donations.” Upon further investigation, however, it turns out Pfalzgraf is employed by Speed.

In response to the backlash, Charles Venable, director of the Speed Museum, argues much of the controversy was sparked by a piece written by Courier-Journal art critic Diane Heilenman. The article suggested that an artist “might just donate the money to the museum, and keep the artwork,” especially since tax laws only allow artists to claim the cost of materials and not the monetary value of their work.

In an attempt to defuse the escalating situation, Venable took to the pages of The Courier-Journal to explain the “democratic” aims of the open call, but to no avail. The “Speed? Baloney!” Facebook page ballooned to 300 members, the majority of which were mainly concerned with the low set price for the art, suggesting it represented a devaluation of their work.

But Venable is quick to explain that this event provided aspiring artists — particularly students — with an opportunity to have their work displayed in a museum. “If you go to the installation, you’ll see people with their families posing for photographs in front of their art and you’ll understand what this opportunity was all about,” Venable said at Friday’s event.

That explanation, however, did not resonate with some, as evidenced by this post on the “Speed? Baloney!” one day after “Art After Dark”: “I hope the museum does a better job tapping into the talents of the Louisville community. We have an outstanding artist community — far better that what was represented in those 5”x7” ‘tastes’ of art.”

“So what’s being said here by Louisville’s marquis venue is that Louisville art is only worth $27 dollars,” said Paul Paletti, a local artist who attended last week’s “Art After Dark.” Owner of the Paul Paletti Gallery on East Market Street, he further stated that an artist would have to “bastardize” and intentionally “cheapen” their work to accommodate for the $27 price tag.

Local artist Aron Conaway feels the cause of this tiff runs deeper that this specific incident with Speed: “I think the bottom line is that there are some serious issues with how the arts at large are treated in this city, a problem that is decades old. The Speed simply chose a bad time to do a fun, yet uninspiring project that for once acknowledged and banked on many of the artists to whom they have given the cold shoulder for decades.”

During a recent phone interview, Conaway — administrator for the Louisville Visual Arts Association — spoke about gallery owners, whose efforts years ago helped develop East Market Street into its current boon. At the time, they didn’t get any help from the city of Louisville or Speed, and Conaway suggested frustrations between East Market galleries and Speed might still exist.

It’s a sentiment shared by online poster Emily Ritter, who criticized Speed’s support of local artists: “I’d like to see what ideas others have about making the relationship between the Speed and local artists stronger. Personally, I’ve wondered why — although it is good enough to use as a fundraiser — local, Louisville art is not represented in any permanent capacity at the museum?”

In defending the decision to be selective when choosing artwork for the Speed’s collection, Venable said he doesn’t want to “create a ghetto for Louisville art.” The museum’s director further expressed his aversion to devoting a wing exclusively to Louisville artists, explaining that such a separation would suggest a lesser standard. “We’re only looking for the very best … and we want our Louisville pieces to stand alongside the very best the world has to offer.” Indeed every museum has to walk a fine line between bolstering the community and maintaining a “world-class” standard. But the fact that Speed sustains “world-class” standards yet has only one contemporary Louisville artist on exhibit (a collection of photographs by Sarah Lyon) suggests to some that Speed thinks there’s only one Louisville artist worth current attention.

“Speed could’ve used this event to promote local artists instead of devaluing them,” Paletti said. When asked if his own photography gallery exhibited any Louisville art, however, Paletti said, “No, but that’s not my mandate. I bring in work of national and international reputations, who are technical masters of what they do.”