Slicing five miles through Louisville’s downtown, Broadway shows just how challenging it can be for a sweltering urban center to beat the dangerous summer heat.

Louisville’s main drag leaves the upscale and relatively-leafy Highlands neighborhood and heads west, where it widens to seven lanes of black asphalt and enters a stretch of office buildings and parking lots — and a distinct paucity of trees to offer any shade.

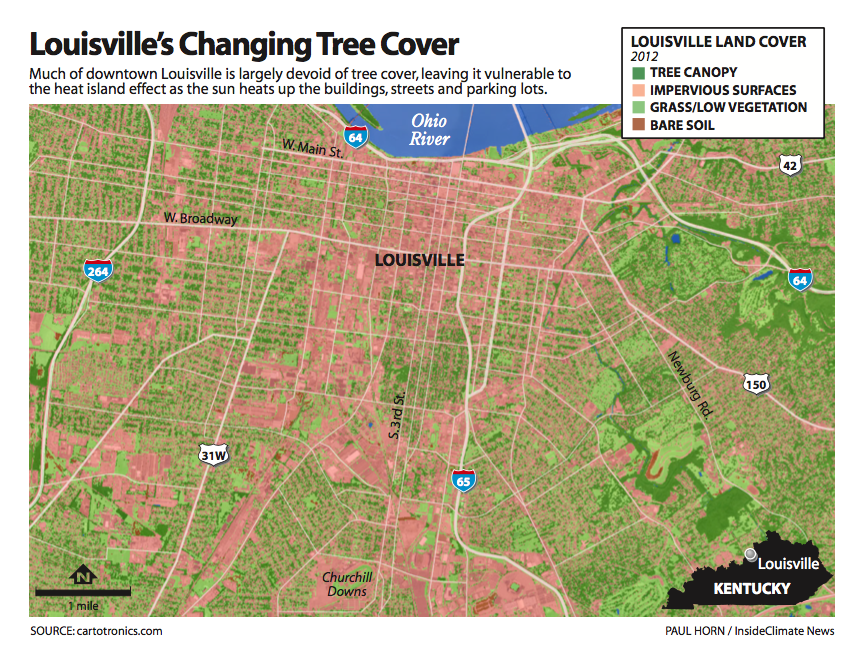

This city, long known for horse racing, has recently gained notoriety for a much less welcome distinction: a rapidly expanding urban heat island. More noticeably than in any other large American city, Louisville’s urban core has been heating up faster than its edges.

In a summer that has set heat records across the Northern Hemisphere, there’s a growing awareness that rising global temperatures are also exacerbating the heat island effect that’s baking urban centers in the day and leaving them unable to cool down at night. Some cities are trying to respond, but they’re discovering enormous challenges.

Louisville launched a limited program to subsidize cooler, reflective roofs, and it has been planting trees. The new tree numbers since 2011 are approaching 100,000, and saplings sporting irrigation bags around their skinny trunks offer hope of shady sidewalks in years to come.

But on Broadway, there are still blocks with many more telephone poles than trees, interspersed with vacant tree wells cut into sidewalks.

“Empty trees wells are the mark of a failed arboriculture program,” said William Fountain, a UK professor of arboriculture, as he walked along Broadway on an August day. “We don’t know what was once planted here,” he said about one of them, “but the weeds are doing fairly well.”

Trees can do a lot to stave off warming, well beyond providing shade, but they need to be nurtured. Instead, they face heat, drought, pollution, vandalism, car accidents and toxic road salt. And, Fountain said, cities such as Louisville weren’t planned with trees in mind. There isn’t space for their canopies or enough soil for their roots. Some sidewalks even have basements below.

Instead, trees are an afterthought.

“Trees are not viewed as a necessity,” said Fountain, who argues trees are every bit as important to a city as water, sewer and transportation systems. “We could put utility lines underground, but we cannot live without trees.”

Not Just Louisville: Urban Tree Loss Is a National Problem

In 2012, Brian Stone Jr., a professor and director of the Urban Climate Lab at Georgia Tech, was the first to document Louisville’s burgeoning urban heat island.His findings spurred a tree canopy assessment, a follow-up heat-management study that he wrote, the formation of two new nonprofit groups focused on tree planting and tree education, the revamping of a street-tree ordinance and a debate about how far local government should go to help provide relief.

“Summers are getting longer and hotter and unpredictable heat waves occur all the time,” said Maria Koetter, the city’s sustainability director. “We want to be out in front of that.”

Stone’s revelation came as the city, the center of a metro area of 1.3 million people, was recognizing that decades of neglect, powerful storms and disease had taken a serious toll on its tree canopy.

It’s a national problem, said U.S. Forest Service researcher David Nowak.

“We have found, pretty much across the board, most states are losing their urban tree canopy cover,” said Nowak, who blames both natural and human-made causes, such as diseases and land development.

Nationally, urban tree losses add up to hundreds of thousands of acres and 36.2 million trees per year and a corresponding depletion of all their benefits, including air and water pollution reduction, carbon storage — and cooling. Rhode Island, Georgia, Alabama, Nebraska and Washington, D.C., have been losing the largest percentage of urban trees annually, according to a new study by Nowak and a colleague.

With urban heat islands adding to the rising temperatures from climate change, “cities are going to take the brunt,” Nowak said. “If we can cool our cities by one or two or three degrees, it’s going to be a huge impact.”

How Do You Cool an Urban Core?

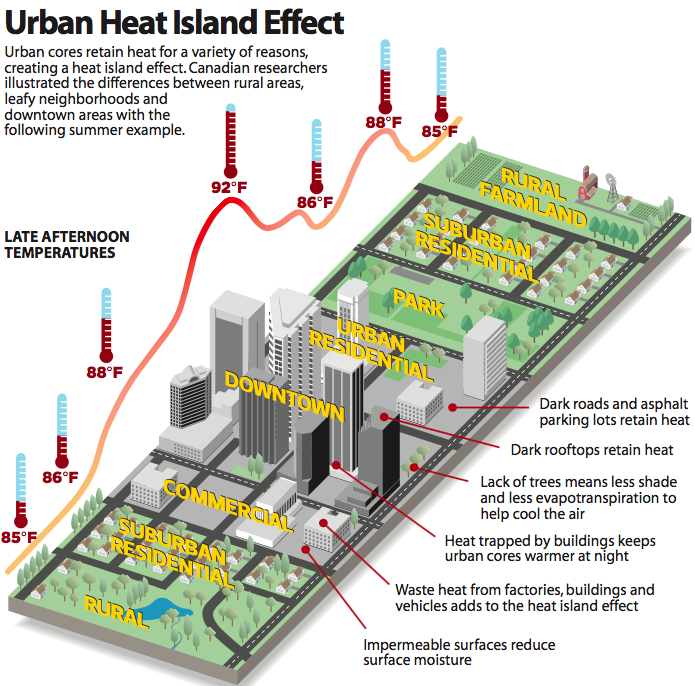

Cities get hot for a lot of reasons.Cars, buildings and industries emit waste heat. But so do air conditioners, creating an ironic feedback loop. Buildings and pavement radiate heat into the evening, long after the sun has set, keeping some cities dangerously hot late into the night.

In Dallas, where Stone’s team prepared another heat mitigation plan, he estimated 112 city residents died from heat-related causes during a blistering 2011 warm season. He blamed that city’s urban heat island for half of those deaths.

At stake is the safety and livability of cities across the globe, at a time when urban populations are growing, Stone said. By 2050, more than two-thirds of the global population is forecast to be living in cities, up from just over half now, according to the United Nations.

“The amplification of global warming trends by the urban heat island effect in cities is accelerating the pace of climate change in the very places that are now attracting the most migration,” he added.

Trees are among the most effective ways to cool a city.

Aside from comfort for people enjoying the shade, trees can stop the sun from overheating buildings and they can stop sidewalks and streets from absorbing heat. They also cool the air by evaporating water through their leaves. And they offer habitat for insects, birds and other wildlife.

Sometimes, Solutions Are Easier Said Than Done

In Louisville, the tree canopy study found that the city lost 54,000 trees a year from 2004 through 2012 and that only 37 percent of the city had tree cover compared to more than 40 percent for other cities in the Southeast, such as Nashville and Atlanta. If nothing was done, that could fall to 21 percent by 2052, the report warned.Some neighborhoods, typically those with lower income households, were in far worse shape — already in the low teens for a percentage of tree canopy coverage.

Stone’s heat management study identified the city’s hot spots and found that some areas were as much as 5 to 12 degrees warmer than other areas of Louisville. Stone calculated that heat likely contributed to 86 Louisville deaths in the especially hot summer of 2012, and he outlined a strategy for cooling off.

Planting lots of trees, protecting existing trees and taking other steps, like requiring or incentivizing lighter-colored rooftops or rooftops with vegetation, could lower temperatures by as much as 5 degrees, cut heat-related deaths by 20 percent and improve living conditions for hundreds of thousands of people, according to his report.

But moving on those recommendations is easier said than done in a city confronted by tight budgets, political pushback from business interests and an overall lack of appreciation for trees.

To meet its goal of 45 percent tree canopy, the city estimates that Louisville needs to plant 186,000 trees a year for a decade and a total of 3.5 million over 40 years at a potential cost of $1.6 billion. Right now, nonprofits, businesses, residents and the city are estimated to be planting 10,000 to 15,000 trees a year.

Even Atlanta — known as “a city in the forest” — with its vaunted tree canopy coverage of about 48 percent is struggling to get to its goal of 50 percent. Development pressures there are intense and fueled by renewed economic growth, said Tony Giarrusso, a Georgia Tech researcher who studies that city’s tree canopy.

“Once you chop an acre of canopy coverage, it will take you 20 or 30 years to get that back,” he said.

Citizen Foresters, Importance of Education

TreesLouisville is one nonprofit trying to build up more tree canopy where it’s needed most, including sun-baked schoolyards. It recently planted 70 trees at Maupin Elementary, one of Kentucky’s lowest-performing schools, in Park Hill, a low-income, low-canopy neighborhood just south of Broadway.“When I came here three years ago ... the only shade we had was what was created from shadows of the building and a corner tree,” said Principal Maria Holmes. “Though the (new) trees are still getting established, the transformation is incredible.”

“Any elementary school kid can tell you the value of trees, but by the time we are adults, it’s not something we see or acknowledge,” she said.

Louisville Grows, another new non-profit, has taken a different approach. It developed teams of “citizen foresters” and other volunteers who have planted and nurtured 2,500 trees in people’s yards, mostly in lower income neighborhoods.

Canopy Protection Falters

Increasingly, cities are starting to recognize the problem of urban heat, even as progress is slow, said Kurt Shickman, executive director of the Global Cool Cities Alliance, which works with cities and businesses to promote cool roofs and pavement.In the Deep South and across the American Southwest, many building codes now require cooler roofing for flat-topped commercial buildings, he said.

Atlanta is updating its tree canopy assessment. Chicago has hundreds of green roofs. Austin, Texas, protects its largest trees, even those on private property and mandates at least one tree within 50 feet of each parking lot space. Los Angeles is starting to paint streets white and require cool roofs that reflect sunlight.

Just one shift can make a difference, Shickman said, like how Los Angeles’ cool roof ordinance in 2014 has resulted in lower-priced “cool shingles.”

In Louisville, protecting existing tree canopy is also critical. But even after Stone’s warnings, Louisville was unable to pass a comprehensive tree protection ordinance. After three years of debate, the Louisville Metro Council instead decided to require that lost street trees be replaced, but only those in the city’s public rights of way.

Parking lots are another thorny issue. Downtown Louisville has 380 surface parking lots, enough for 20,000 cars and many have few or no trees in them.

Until last December, city officials had held up as a shining example for others a private parking lot with more than 40 mature trees that were planted decades ago to offer a shady oasis amid the blacktop. But the parking lot’s owner, the Courier Journal, Kentucky’s largest newspaper, legally lopped off the tops of the trees to clear views for security cameras. Now, many of those trees are dying. “It’s in such dismal condition,” Fountain said. “It’s lost its value.”

The pushback in Louisville is not uncommon, said Cooper Martin, a sustainable cities program director with the National League of Cities, with a membership of more than 1,900 cities.

For many cities, a big challenge is persuading enough taxpayers that urban heat is a serious enough problem to spend money on, when a lot of police departments, health departments and other city services still haven’t recovered from the recession.

A new mindset may have to wait for a new generation.

“As younger residents demand a higher quality of life in urban environments,” Stone said, “they are effectively endorsing more climate-responsive design.” •

James Bruggers, the former environmental reporter for the Courier Journal, writes for InsideClimate News, a Brooklyn, New York-based Pulitzer Prize-winning, nonprofit, nonpartisan news outlet that covers climate, energy and the environment. Sign up for the newsletter and learn more at insideclimatenews.org.