Three battered men slide off a sky-blue mat like melted butter. Marcus Anthony, a Goliath in red spandex, just body-slammed them like a slugger in batting practice — wham, wham, wham — barely shrugging at their attempts to take him down.

A passionate crowd heaves with rage once a dainty hammer hits the bell, calling the match.

“You Suck!”

“Punk!”

Anthony puffs, flexes. Two sinewy mounds emerge on either side of his neck, creating a near-perfect triangle from the tip of his mohawk to his shoulders.

When Anthony’s biceps pop, they’re a mirror image of Ohio Valley Wrestling’s logo — two curled, golden arms.

OVW is a wrestling promotion company. In 1999, it was tapped to become a kind of minor leagues for World Wrestling Entertainment (then World Wrestling Federation).

OVW moved to Shepherdsville Road, a pocket of the Buechel area sectioned off by working-class neighborhoods, open fields and industrial parks. In a collection of nondescript, toffee-colored warehouses, behind a lighting supply company, lies sacred ground for local wrestling fans.

It’s here, underneath the lights of OVW’s Davis Arena, where more than 100 WWE wrestlers have gotten their start, including current mega-star John Cena.

Tonight, the smell of popcorn drifts over a momentary lull in action. Giddy children recount each wallop, hurling invisible opponents over rows of aluminum chairs.

Donna Payton leans on her cane and hoists herself out of the front row, walking a few steps to the barricade holding back the crowd of about 60. Donna’s sister, Mary, follows.

The middle-aged sisters, both with glasses and loose T-shirts, travel here from Elizabethtown religiously. A few dozen more fall into this category of super-fans — dolled-up teens, dressed-down families, lonely singles, and weekend-warriors who launch into trash talk with, “When I was wrestling …”

Mary points to her sister.

“She’s even had a heart attack here.”

Donna nods and gives me a you-better-believe-it look.

Life and death. A perfect storyline for a pastime often equated to a soap opera. But here, voyeurs double as participants. Passionate taunts are lobbed just a few body lengths away from their intended targets.

Intimacy is a key draw. But that hasn’t been enough lately.

In 2008, show attendance dropped. That’s the year WWE separated from OVW and created its own developmental program in Florida, taking with it money, big names, even the pay-per-view posters that lined the arena’s 8,000 square feet.

“It isn’t cheap to operate,” says Danny Davis, OVW’s owner who says WWE’s contract was worth $1 million a year. “It’s been tough.”

Davis says he’s used $600,000 of his own money to keep the doors open.

What OVW didn’t lose was its reputation as a strong training ground. Dozens vying for that elusive WWE contract come to learn the mechanics of wrestling and the craft of hooking fans.

Speakers crackle and heads swivel to see who’s coming in next.

Motley Crue’s “Girls, Girls, Girls!” shrieks over the speakers.

“Sexy Sean Casey!” growls the announcer. Casey salutes the audience with a series of pelvic thrusts. Donna jeers, recognizing (by the direction from which he enters the arena) that he’s a bad guy, aka a “heel.”

“Shut up!” Casey snarls, snapping his gaze directly at her as she taunts him.

“No!” she says through a smug grin.

Wrasslin’ school

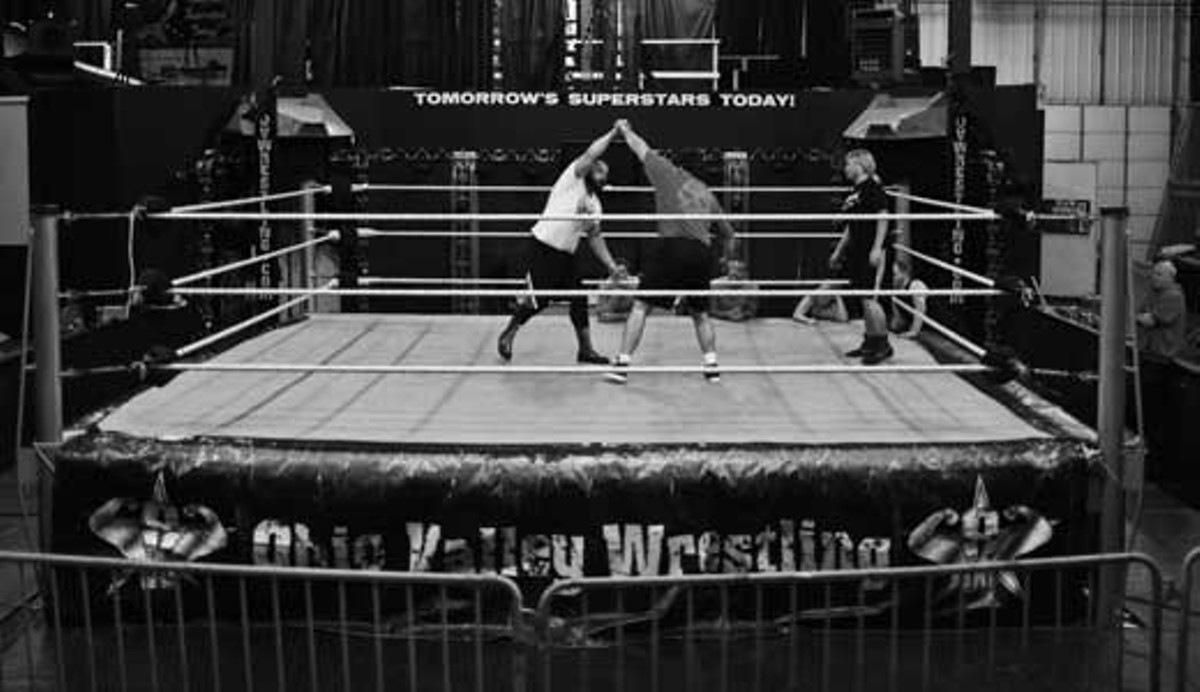

On a warm Monday evening in early September, eight men and a woman make small talk inside musty Davis Arena. Tonight is initiation — the start of the beginners’ 10-week training course. Above the mat hangs a gold and black banner with the bold promise: TOMORROW’S SUPERSTARS TODAY!

One is a teacher, another an actor. All have aspirations of pro-wrestling coursing through their veins. They hail from Austria, Bermuda, and the sole woman in the pack just arrived from Australia.

It’s Courtney Hazell’s first time in the United States, her first time living without her parents, and her first time wrestling.

Hazell’s in her early 20s, with straight blonde hair pulled away from her thin face and knotted into a tight ponytail. She looks around the room at her fellow students.

Frames range from cross-country runner to linebacker. The most striking belongs to a 6-foot-5 bald New Yorker, seemingly assembled at Rikers Island. Tattoos spill down his arm. A strap of dark hair traces his scowling jaw-line.

“I don’t really want to throw these big guys over my shoulder,” laughs Hazell, who has an athletic, sturdy build. “But, we’ll see.”

She’s watched former OVW wrestlers for years and can rattle off success stories. Her personal favorite is a “hot” Cody Rhodes.

“Don’t laugh at me when I show you this,” she says as she pulls out a plastic Cody Rhodes figurine from her gym bag. It traveled with her on the plane and posed on liquor bottles at her going-away party.

“My mascot,” she jokes.

A bearded man with chin-length frizzy curls silences the room. He wears professorial glasses, proper for a place that claims it is the “Harvard” of professional wrestling.

“I’m Nick Dinsmore. This is the Nick Dinsmore pro-wrestling class,” he says, looking at the nine students scattered in folding chairs.

“What I hope each one of you achieves at the end of the class is to fall correctly, take bumps, run the ropes correctly, give a set of moves that almost everyone in the wrestling business can do: a hip toss, a body slam, a drop kick.”

Dinsmore is a draw for a lot of students. His career started at OVW. In 2004, he catapulted into the WWE spotlight with a character named Eugene, an apparently mentally challenged wrestler with a scribbled nametag pinned to his jacket. His mannerisms blended Rain Man with an oversized toddler.

But when the bumbling clown executed textbook moves, the crowd roared.

“He’s an exceptional performer who knows how to wrestle,” Mike Mooneyham, a sports writer and keeper of the country’s longest-running pro-wrestling column, wrote in June 2004.

The character initially drew criticism, but in three years, Dinsmore had thousands chanting his name at shows, along with four action figures.

“Nick can teach anyone to wrestle,” says Sean Conway, the lone Louisvillian in the class. His uncle, “Ironman Rob” Conway, is a household name to OVW fans.

Dinsmore has the students hop in the ring and immediately instructs them to throw themselves flat on their back from a standing position. They land with their knees and feet bent as if still sitting, arms splayed at their side. It’s the first of many “bumps” they’ll endure.

As bodies drop, a sharp, metallic hammering sound echoes from the concrete walls.

Hazell goes down in pieces, swatting her head on the mat. Even when she gets it right, she feels the wind knocked out of her.

“Whenever you fall, you want as much of your body on the mat as possible,” Dinsmore says. “If you land in sections — boom, boom, boom — it’s gonna hurt.”

The pain is monotonous. In the next three months, this crew will have torn knee ligaments, mild concussions, and raw, cloudy bruises mapped out across their flesh.

Dinsmore reminds me that wins and losses may be pre-determined, but the moves often aren’t scripted. If done wrong, you’ll get injured. If done well, they’ll still hurt.

Within one hour on this first night, Dinsmore has them flipping through the air, as one does off a diving board, and landing flat-backed.

Hazell whispers, “I don’t think I can do that.”

She’s not the only one who’s nervous. I close my eyes for most of the attempts. Against gravity and logic, everyone eventually takes a turn, and necks remain intact.

After these moments of blind determination, some students step out of the ring with loopy grins, occasionally dizzy from the fall, but mostly thrilled to share an experience they’d only watched from their couches for years.

This kind of professional mentoring is still a relatively new phenomenon, with training schools like OVW starting to spring up in the ’90s.

“Fantasy camps” is how Larry DeGaris, a professional wrestler with a doctorate in sports sociology, labels them. In OVW’s case, anyone with a high tolerance for pain, a dream, and $1,000 can give pro-wrestling a try. Those willing are guaranteed at least a hobby, and if they’re lucky, maybe a job.

“The vast majority of people aren’t going to do anything with it,” DeGaris says. The small, independent circuit can pay $40 to a couple hundred bucks for a show. Overseas, in Japan and Australia, the pay is better. But overall, it’s tough to make a career out of pro-wrestling.

In the 1980s, Vince McMahon, WWE’s longtime leader, transformed pro-wrestling by taking it to a national, then international stage, raking in profits and gobbling up the brightest talent in “regional territories,” forcing smaller operations to close.

In those days, wrestling was a full-time job. Performers got paid to hop from city to city each week. It wasn’t a life full of endorsements and movie contracts, but it was a way to make a living. OVW’s older fans nostalgically recall the United States Wrestling Association’s (a Memphis territory) stops at Louisville Gardens.

Dinsmore grew up on them.

“Every Tuesday night!” he smiles. “Jerry ‘The King’ Lawler, Bill Dundee, Jeff Jarrett!”

Most OVW students know the history. It doesn’t necessarily alter their own journeys, though.

“WWE. It’s the goal for everyone,” Hazell says. “If they don’t say that, they lie.”

By the end of 10 weeks, Hazell will have made her public debut in a “Divas” costume match on Halloween. Wearing a bubble-gum pink Playboy cheerleading outfit, she left the ring with her chest searing. Five forearms to the chest left cranberry-red lines of burst blood vessels below the collarbone.

It’s the best moment from her time in Louisville.

Her fellow students fared well, too. Only one quit. A promising 23-year-old (who hopes America someday knows the flamboyance of “Ronnie Metro,” an ’80s-inspired egotist) left after getting a staph infection. He blames a dirty mat and a cut from shaving his legs. The 6-foot-5 New Yorker got a WWE audition, but no contract.

Art and craft

If wrestling is an art, than Rig Rogers may be its foul-mouthed Martha Graham. He teaches the give and take, the dance between wrestlers, how each move must blend into the next, how to sell each hit and lose so well that even a 150-pound car mechanic looks like The Rock.

“We can make chicken salad out of chicken shit. And we teach wraaassliing here,” he says. “I can’t make you go to the fucking gym … but I can show you everything that’s up here.” Rogers taps at his head.

He rose to fame in the 1970s, with his peroxide-blonde hair and Herculean physique, as “Hustler” Rip Rogers and as part of a hefty tag-team trio called The Convertible Blondes.

Now, at 57 years old, salt and pepper gray has replaced the blonde. A barrel chest hints at a former grandeur. In 2003, he lost his ability to wrestle with students. That’s the year a car hit him, leaving him with a stiff limp. But he keeps a phone in his fanny pack to punch up legendary matches on YouTube as learning tools, many from his era.

It’s a Sunday afternoon. He watches OVW’s advanced class with clenched fists, eyes fixed on students engaged in an impromptu match.

“If there’s no contact, it doesn’t look like it hurts!” he yells.

Listen to Rogers — land on OVW’s roster. It’s that simple. And while OVW does not pay its wrestlers to perform, many don’t seem to mind.

The exposure is priceless.

WWE scouts still peek in. And last month, OVW agreed to be the developmental school for Total Nonstop Action Wrestling, or TNA, a Nashville/Florida-based wrestling promotion company that airs shows on SpikeTV. It’s not the big leagues, but another step out of obscurity can’t hurt.

Even Dinsmore hopes his old employer eyes him.

His three-year stint at WWE is average for most wrestlers. It wasn’t fickle management that got him cut, but a busted knee. Eager to return, Dinsmore says he relied heavily on prescription pain pills and got hooked. After failing a drug test, he was released.

The 35-year-old still lands steady gigs: upstate New York one weekend, Nashville a few weeks later to judge a pinup contest with ’80s pop icon Tiffany. But the performer in him wouldn’t mind one more run on the industry’s premier stage with a new character — this time, a villain.

The metamorphosis from “baby face” (good guy) to “heel” is tricky. Wrestlers must craft Jerry Springer-like explosions with persuasive monologues.

Gone is Eugene’s inside-out jacket. Now, Dinsmore wrestles in blue and red spandex tights, “Mr. Wrestling” stitched on the rear.

At a recent Wednesday night show, the college communications major improvises for the hungry mob at his feet.

Fan favorite Jason Wayne stands inches from him. The grudge stems from a snubbed handshake.

“That’s what this is about? A handshake?” Wayne asks.

“YUP!” fans scream. “There you go!”

“You stole my thunder. You’re a ball hog,” Dinsmore says. He tugs on his beard, paces a bit.

“FIGHT! FIGHT! FIGHT!” The room tremors with anticipation as the two bare-chested, glistening men emote.

Wayne offers Dinsmore his hand.

Then comes the quake.

Dinsmore spits in it.

“OHHHHHH!”

Punches connect. The clash swirls about the ring like water down a drain. Dinsmore, forced onto the top ropes, fends off blows, and head butts Wayne a little too hard, splitting his eye open.

In Kentucky, bleeding in the ring isn’t allowed, so the match stops. It will take 12 stitches to close the cut.

“Nick, you feel like a man now?” a fan shouts.

After the match, as Dinsmore wipes channels of sweat from his face, Wayne walks by with bandages wrapped around his forehead. Dinsmore leans over to me.

“Got him,” he grins devilishly. Classic heel.

Forever fans

Disclaimer: I’ve never been much into wrestling. I have no idea what Jake the Snake’s finishing move is. I’m not much into violence. I smile at the campy but squirm a bit at the sexism.

Still, like most Americans, I’ve been sucked in before.

My late Sicilian grandfather introduced me to the legends as a kid: Randy “Macho Man” Savage, Andre the Giant, Junkyard Dog.

He’d stand and curse in Italian at the WCW and WWF matches on TV, getting so enraged he’d choke on phlegm deposited by a lifetime of cigarettes. Not wanting to miss a minute, he’d cough into plastic bags kept stashed under the couch.

That’s what wrestling is about — falling into the drama, gasping at the bumps. Cringe, curse, laugh. Repeat.

I doubt I’ll ever berate refs or collect autographs, but I’ve found myself Googling “Wrestlemania” videos under the guise of research and amassing friends for an OVW “house show” at the St. Therese gym in Germantown.

It’s hard not to be entertained. When sinister Raul LaMotta enters? The crowd froths with a chorus of “Taco Bell! Taco Bell!” A die-hard insists LaMotta works there.

Or, take Paredyse, a crowd-pleasing, sometimes cross-dressing eye shadow enthusiast who bounds on stage with a wood nymph’s nimble glee. Should his opponent be slumped in a corner, Paredyse sits on the ragdoll’s sternum, bouncing up and down like a baby on daddy’s knee.

“Kiss him!” a few rabid fans cheer.

The smaller wrestlers impress with acrobatics. Blink and you’ll miss Randy Terrez’s lucha libre-inspired finishing move — a back flip off the top ropes that corkscrews and ends with a belly flop onto his opponent.

I’m told OVW’s seen a slight uptick in attendance in the last few months. The challenge will be hanging on to them.

DeGaris, the pro wrestler and sports sociologist, says this kind of entertainment tends to have a shelf life for most people. Eccentricity’s grand high doesn’t create an addict.

He says building in simple universal truths to each performance can help.

“A lot of these themes are really simple,” he says. “Suffering, justice, revenge, honor.”

Al Snow is committed to filling Davis Arena. If you’ve watched WWE in the last 15 years, or the wrestling reality show “Tough Enough,” you may know the name. Snow is currently a trainer and show producer for OVW.

He worked here during the days of the WWE-OVW partnership, left for a while and returned in the spring. He noticed the roped-off section of empty seats at shows (so that cameras taping the show only capture angles with a healthy audience) and felt like wrestlers were too focused on technique, not with connecting to the crowd.

“There were no stories being told,” he says.

So he assumed the duty of narrative wizard, devising clumsy theater to accompany cartoonish violence.

An hour before Wednesday night shows, one question is asked a dozen times.

“Where’s Al?”

Wrestlers scurry to him seeking wardrobe approval, direction on their lines and the motivation behind them.

Snow still looks much as he always has: long hair, goatee and broad shoulders. Only the use of reading glasses reflects age. He gathers three key players for the night’s drama: Christian Mascagni, Mike Mondo and Rudy Switchblade, a street-fighting type who rants about thought crime and quotes Orwell on the mic. He’s currently OVW’s title-holder.

Mascagni, a local criminal defense lawyer and pro-wrestling fan, jumped at the chance to play a much-maligned OVW manager. He was cast after defending a few wrestlers (in real life) for “minor stuff,” he says. With his Lex Luther look and eager salesman’s grin, it’s a well-cast role.

“OK,” Snow says looking at Mascagni, who “manages” both Mondo and Switchblade.

“You go in with Rudy, and (Rudy) you are just happy as a pig in shit because you’re the heavyweight champ. “

He turns to Mondo, who is the “baby face.” Tonight, he’s the guy getting screwed. The guy being ignored by his boss, Mascagni, who is focused on promoting Switchblade instead.

Mascagni scribbles notes on a day calendar, so excited that his eyebrows quiver. It’s his job to make Mondo look like the underdog who, by the end of the skit, will have usurped the crowd’s affection.

With 30 years in the industry, Snow comes up with a lot of this on the spot. He always reiterates that every line and gimmick is just as important as nailing the pile driver.

First, they have to learn the moves, Snow says, “And then the real training is to get out in front of these people and tell the story that will be able to manipulate the emotions to a peak, and that will then motivate them to pay to see them again.”

With a half hour to go, doors open. Familiar faces hustle in, young and old.

Mary and Donna Payton take their regular seats.

On any given Wednesday, the sisters know the night’s signature match will usually involve a handful of wrestlers, Jason Wayne being one. When he bounds into the ring, teenage girls shriek with delight, holding up empty, eager hands or construction paper with scrawled messages of love and support.

Wayne, a former Marine with boyish features and a football player’s build, typically snatches his dog tags off, handing them to a lady in the crowd. Tonight, he hangs from the ropes, one arm dangling at his side, and gazes into Donna’s eyes.

She cups her hands, like a Catholic about to receive communion.

Wayne yanks his tags off, but tenderly places them on a corner of the mat.

“You should’ve raised your hands!” says a man behind Donna.

“No, I don’t need them. I have some right here,” she says, patting the white purse at her hip.