Chef David Clancy is unemployed again. In the fall of 2007, he was forced to give up his dream and close his beloved Bistro New Albany on East Market Street in downtown New Albany. Since then, he has taken at least three positions, the most recent at The Speakeasy on State Street a few blocks away from his old digs. On Friday, the word was out: The Speakeasy would also be closing as of this weekend.

“This is a horrible time to own any business, much less a restaurant where the margins are so scant,” Clancy says. “I am thankful I shut down when I did, as I would probably be swinging from the rafters right now if I hadn’t. Yes, I lost everything by betting on a new restaurant in a speculative town but … timing is everything.”

Clancy also blames the skyrocketing cost of supplies and materials. “Restaurants are faced with the challenge of passing these costs on to the consumer — a deadly choice in the long run if you want to keep a clientele — or absorbing the costs and simply bucking up,” he says. “Independent restaurants are going to suffer the worst, as they do not have the luxury of buying power, proprietary sales, volume discounts, or triple-A credit like the larger chains. My fear is that so many independents will fall by the wayside in this current economy that all we will have left, as far as the eye can see, is chains.”

A recession is technically defined as “two or more consecutive quarters of negative growth.” Now, I’m no financial wizard, but even I can figure out that means you won’t be able to formally identify any certain economic slowdown as a true recession until we’ve all been feeling the effects of it for half a year or so. So even though the experts are still resisting labeling the current situation as a “recession,” we know it when we see it and feel it.

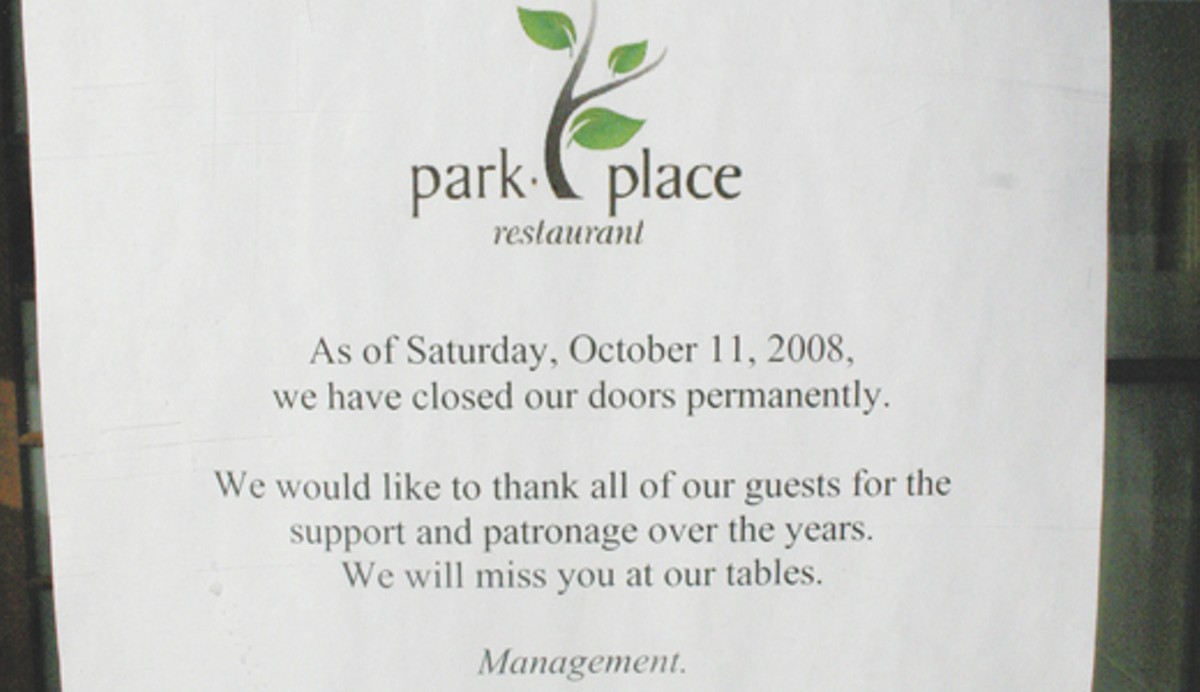

One huge indicator is an increase in the number of restaurant closings. Do you realize how many Greater Louisville restaurants have closed in the last several months? Included are names like Caffe Perusa, Primo, Frank’s Steakhouse, Ferd Grisanti’s, Da Vinci’s, Nio’s, RockWall in Floyds Knobs, Park Place and Browning’s at Slugger Field, Sweet Pea’s on Frankfort, Omar’s Gyros, Sahara Café on Lexington Road, Rick’s Ferrari Grille, Frolio’s Pizza, Pepper Shaker BBQ, Bistro New Albany, Kunz’s The Dutchman in downtown Louisville, and Stratto’s in Clarksville. The list gets longer every day. I cringe when I see a “Closed temporarily for remodeling” or “Closed for family emergency” sign on a local restaurant. Many times, temporary turns into permanent.

In order to avoid the same fate, chefs, owners and kitchen managers are forced to be practical. This summer, when lots of local restaurants saw a decrease in business, many chefs/owners scheduled whole shifts alone in the kitchen, working solo to save on payroll. Dishwashers (less expensive by the hour) were trained to do simple prep work normally given to a more expensive by-the-hour prep cook. Shifts that normally require two dishwashers now feature one.

Then came the Great Windstorm of September. Mother Nature blew a wind tunnel from the Gulf through the Midwest and into the north, via Hurricane Ike. Dozens of area businesses, including restaurants, lost power for hours that turned into days. I’m one cook who had no shifts from Sept. 14-19— you can imagine the effect that had on the next paycheck.

Some restaurants were forced to rent/buy/borrow ranks of generators and present limited menus by candlelight — just to be able to open and have some money coming in. I ask Jay Hignite, the manager on duty at August Moon on Lexington Road, what sparked their decision to open for dining on generator power during the aftermath of the storm, rather than just using generators to keep inventory from spoiling.

“Well, a salaried staff, mainly,” Hignite says. “Three-quarters of our kitchen staff is on salary.”

That means they had a choice between paying staff to stay home or paying them to come in and open the restaurant in an attempt to recoup some losses. But they could only serve a limited menu. “It was pretty wild,” Hignite remembers. “We couldn’t offer any grill items, because we didn’t have generator power to the range hoods. We had to rent a big five-foot fan to suck the smoke out of the kitchen.”

Some restaurants had business-loss insurance that only kicks in after you’ve lost a certain number of thousands of dollars. Fretting over the first couple days of power outage suddenly turned into praying for the power outage to continue for a few more days so the minimum loss requirement would be met. Unfortunately, many had no business-loss insurance at all and lost thousands of dollars’ worth of food during the power outage. Then they had to pay workers to come in and throw away spoiled product while they were still closed and not bringing in any income. Some restaurants just weren’t able to re-open. Ever.

Stacy Roof, president of the Kentucky Restaurant Association, tells me that restaurant owners who are not well established already have a hard time borrowing money in normal financial circumstances. But borrowing — even for well-established businesspeople — is more difficult now due to the tightening credit market.

“So savvy operators are always looking for ways to increase their bottom line,” Roof says. She points out that many food service businesses are revisiting contracts and sales agreements for the things they use every day. While some have stubbornly stuck to an “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it” attitude toward their vendor relationships, others have taken advantage of the changing financial landscape to implement policies and procedures they may not have had time to examine closely when they were busier. For instance: A restaurant may have put off “going green” (implementing environmentally-friendly policies such as recycling and using compostable vegetable-matter to-go containers), but may find that easier to achieve now that they have some spare time. Some are even finding that environmentally friendly policies (such as replacing regular bulbs with low-energy compact flourescent light bulbs) save them money in the long run.

The price of supplies has increased, too. Roof notes that higher gas prices have had the effect of driving up food costs, and restaurateurs are paying about 29 percent more this year for goods such as flour, cheese, poultry and beef. I interview a sales rep for a national food service supplier who disputes this, saying that while the prices of some product categories have spiked recently, many of them have come back down to near where they were at the beginning of the year. I mention that restaurants haven’t seen the “fuel surcharge” dropped from supplier invoices, despite somewhat lower gas prices recently.

“As the distributor, we have to pay for transportation of product coming in and going out, and the cost of diesel fuel has increased dramatically,” he says. “Really — there’s only been about a 6 percent total increase in commodities prices across the board this year.”

In a business where the average profit margin — even in good economic times — is between 3 and 5 percent, well … you can do the math.

A recent National Restaurant Association newsletter said that this year, more than ever, concentration on drink specials to drive traffic is garnering some success. But the prices of spirits and beers have gone up dramatically, according to Andrew Hutto of Baxter Station and co-founder of the Louisville Originals (an association of independent restaurants in the Metro area).

“I think one of the biggest mistakes we’ve all made as independents is we spend so much time trying to keep prices low — can’t raise prices, can’t raise prices — ’til your back’s to the wall and your only alternative is to raise prices,” he says. “We have not laid anyone off — mainly re-evaluated prices on spirits and beers.” Some of those prices had been static for many months or years. “Then you have the folks that come in and mention that ‘that’s quite an increase in the price of that beer,’” Hutto says. “I just want to say, ‘Hey, be happy, you have been underpaying for it these last three years.’”

Another strategy for lean times is to be flexible and nimble with your business plan. “I guess what we’re leaning on right now is the catering portion of our business,” says Anne Shadle of the Mayan Café on East Market Street. “Being a downtown business, we’ve had to diversify to make it work. Catering often makes up for the slow nights and then some.”

Sometimes, though, rumors fly. An executive chef at a popular East End eatery tells me the story of how a TV news crew came by the restaurant one afternoon requesting an interview. They wanted to ask him about the recent spate of restaurant closings. The chef gave his views about the economy’s effect on the dining industry in a brief “local flavor” segment. Soon after, the restaurant got a series of calls: “We’re so sorry you’re closing” and “When’s your last day … we can’t believe you’re closing.” Serious second thoughts about media interviews ensued.

All is not gloom and doom. Christopher Stockton owns Jackson’s Organic Coffee, a small coffee shop at the intersection of Lexington Road and Payne Street. He started the company along with his partner about 18 months ago, near the beginning of the economic downturn.

“This may seem like a terrible time to start a company, but I actually feel like it has made us stronger, more independent and sustainable,” he says. “I say this for a number of reasons — we were never given a large amount of credit and we had very limited funds to begin with. So, in effect, this has kept the business honest. In other words: If we can’t afford it, we can’t have it. Or, if it’s not homemade, handed down or recycled, we can do without.”

It also means they do everything themselves. This includes running the drive-thru window, roasting coffee, packaging and retail delivery, servicing their own equipment — and so forth. Still, Stockton’s advice to any potential small business owner in Louisville is upbeat: “Go for it. It can be done — even in this dreadful economy. You just may have to tighten your belts and be willing to do whatever it takes to make your dreams happen.” ![]()

Marsha Lynch is a graduate of Sullivan University and has worked at many Louisville independent restaurants including Limestone, Jack Fry’s, Jarfi’s and L&N Wine Bar and Bistro. She is now the pastry chef at Café Lou Lou.